English | 中文

From the barriers of language, culture and politics, to the logistical challenges of war, revolution, isolation, internal upheaval, government restrictions and changing technology, covering China has been one of the most difficult of journalistic assignments. It’s also one of the most important. For over sixty years, what American correspondents have reported about China has profoundly influenced U.S. views of the country, and the policies of successive American governments.

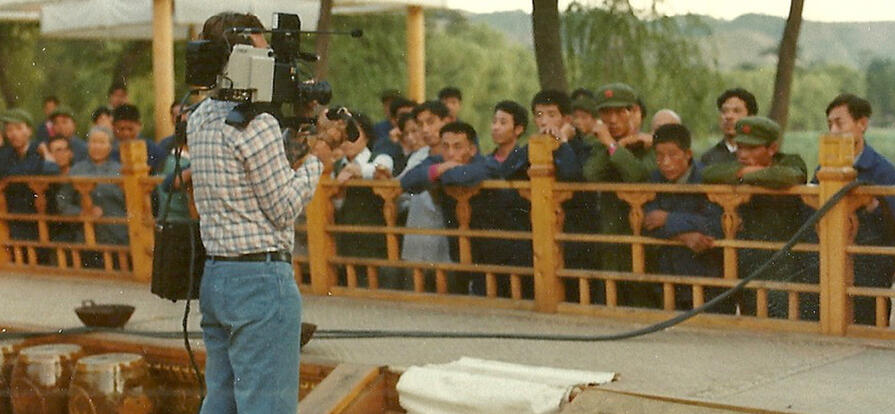

Interviews with these journalists are the core of Assignment: China which is illustrated by archival news footage and other images. This includes previously unseen home videos and other materials. In addition to interviews with those whose work was featured on American front pages and broadcasts, the series includes interviews with Chinese and American officials who sought to manage coverage of China or of specific events, such as Nixon’s historic 1972 trip. For several of the segments in the series, Chinese sub-titled versions are available.

Mike Chinoy, the distinguished former CNN Asia correspondent and USC U.S.-China Institute Senior Fellow, is the writer and reporter for the series. He is assisted by USCI Multimedia Editor Craig Stubing and USCI staff and students, who handle much of the logistics, research, transcription, videography, and editing. Clayton Dube conceived of the project and supervises it.

Assignment: China segments have been screened for universities and organizations across America and China and elsewhere in East Asia. The response from educators, students, officials, and the general public has been enthusiastic and positive. The films are available free of charge at our site and at our YouTube channel. We encourage their use in classrooms. We welcome your comments and hope you’ll invite others to view Assignment: China.

Many individuals and organizations have helped make this series possible. They have given generously of their time and energy, helped us unearth essential materials, guided us to invaluable sources, or provided the financial support necessary to sustain the research, travel, and technical help necessary to produce these compelling films. We thank each of these people and institutions for their help (and we list each in the credits for each segment). We invite you to consider joining them in supporting our efforts (click here to donate, please be sure to designate the U.S.-China Institute's documentaries, or contact us).

Click on the links below to watch Assignment:China at our website. The videos are also available at our YouTube channel (English playlist; Chinese playlist). At the end of the list of episodes are links to interviews we've conducted with China correspondents since completing the series.

There will soon be a book to accompany the Assignment:China series. Written by Mike Chinoy, it will be published by Columbia University Press in 2023.

With the defeat of Japan, the Kuomintang and Communists soon returned to their battle for control of China. This segment focuses on the work of journalists reporting on the civil war that ended with Mao Zedong atop Tiananmen proclaiming the establishment of the People’s Republic.

Largely excluded from China, American journalists in the 1950s and 1960s had to try to report on the tumultuous changes in the world’s biggest nation from its periphery. This segment explores how they did this and how some American news organizations occasionally got reports from within China.

The Week that Changed the World

President Richard Nixon’s 1972 trip ended two decades of Cold War hostility. America’s most famous journalists clamored to go with the president, though most had no idea what they might find, telling us “it was like going to the moon.” This segment shows how both governments worked to shape the coverage and how journalists struggled to report on the historic visit.

While the Nixon trip launched U.S.-China discussions, China was only slightly more open to Americans than it had been. American journalists were only permitted to visit for brief periods. This segment discusses reporting on the period through 1976, when deaths of Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong triggered political skirmishes and the Tangshan earthquake took a quarter-million lives.

With the restoration of formal diplomatic relations on Jan. 1, 1979, American news organizations were able to base journalists in China. The interest in China was enormous, as seen in the coverage of Deng Xiaoping’s visit and of the economic reforms he initiated. The press also paid attention to the new family planning policy and to the stirrings of dissent.

Deng Xiaoping and the reformers he installed in top positions dramatically loosened economic and social controls in the mid-1980s. Journalists for American news organizations documented how Chinese embraced this opening and as some Chinese tested the party-state’s tolerance of dissent. Some journalists, protestors, and even leaders ran afoul of Party hardliners and were punished for crossing hazy lines.

In 1989, students marched in cities all over China, but it was the demonstrations in China’s symbolic center, Tiananmen Square, that captured the attention of people worldwide. Because of the first Sino-Soviet summit in thirty years, there were more journalists in Beijing than usual and the Chinese authorities initially permitted easier satellite access. This segment shows how journalists worked to grasp what was happening and to help their audiences understand the issues and forces at play, ultimately including the violent suppression of the protests.

The 1989 crackdown ushered in a period of political repression in China, but as the 1990s progressed the economy grew, migration became more common, and individual Chinese had greater control over their own lives. While reporters dealt with continued surveillance and harassment, by the end of the decade conditions improved to the point some saw it as the beginning of a golden age of China reporting.

The 2000s were a heady time in China. In 2000, the country won the right to host the Olympic Games and in 2001 entered the World Trade Organization and economic growth accelerated. But soon thereafter, suppression of information about disease outbreaks didn’t just hamper reporters, it threatened public safety. There was rising tension over how some won and lost economically and how the environment was being damaged. At the same time, social liberalization and technological change permitted reporters to explore new regions and issues.

China entered 2008 with great anticipation. Beijing would be the center of world attention with the summer Olympics. But in March repression brought rioting in Tibet and the Olympic torch relay attracted protests outside of China. Then in May, an earthquake killed 70,000 and left millions homeless. Even more than usual, the party-state worried about managing its image at home and abroad. While the games were a huge public diplomacy success, reporters chaffed at the government’s failure to loosen travel and other restrictions as pledged.

The foreign press corps in China hoped that once the Olympics passed, restrictions on their movement and other activities would be loosened. They weren’t. At the same time, the Chinese state invested heavily in expanding its own international media in an effort to override foreign media depictions of China and its policies. While the West stumbled economically, China seemed to have weathered the storm and adopted a more assertive foreign policy. China’s economic rise had led to a dramatic expansion in the American press corps, but covering China’s contradictory trends was no less challenging.

China’s economic rise had been the dominant line in the narrative of the country for two decades. There had long been grumbling about those with connections benefitting disproportionately from this advance. In 2012, two American news organizations documented the immense yet hidden fortunes accumulated by the relatives of Xi Jinping, soon to be China’s top leader, and Wen Jiabao, the outgoing prime minister. Coming after other journalists had broken stories about scandals, the Chinese state punished these organizations and sought to intimidate others.

More from China correspondents:

Book interview with Mei Fong, One Child: The Story Of China's Most Radical Experiment, 2016

Mei Fong reported from Hong Kong and Beijing for the Wall Street Journal and was part of a team which received a Pulitzer Prize for work in 2007 on China's race to prepare for the 2008 Olympic Games. Zocalo named One Child one of the top ten non-fiction books of the year. (Click here for her more extended talk.)

Book interview with Rob Schmitz, Street of Eternal Happiness, 2016

Rob Schmitz was a correspondent for Marketplace Radio (2010-2016) and is now the Shanghai bureau chief for National Public Radio. In this book, he explores the stories of some of the interesting people on Changle Lu (长乐路) in Shanghai. Schmitz first went to China as a Peace Corps volunteer in 1996. He's received two Murrow prizes for his reporting. Schmitz appears in Assignment:China "Contradictions."

Book interview with Louisa Lim, People's Republic of Amnesia, 2016

Louisa Lim reported from China for the BBC and for National Public Radio for a decade, carrying out interviews and research on this look at how the 1989 demonstrations and their suppression are remembered and efforts by the state to squelch discussion. She was part of teams that won Peabody and Murrow awards for reporting on the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. (Click here for her more extended talk.) Lim appears in Assignment:China "Tremors" and "Contradictions."

Book interview with John Pomfret, The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom, 2017

John Pomfret first went to China as a student in 1980. He reported from China for the Associated Press in 1988-1989 and was Beijing bureau chief for the Washington Post 1998-2003. (Click here for his extended talk.) Pomfret appears in Assignment: China "Tiananmen Square."

Julie Makinen, Jonathan Karp, and May Lee, 2017

Julie Makinen, now the executive editor of the Desert Sun, was Beijing-bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, 2013-2016; Jonathan Karp, former executive director of the Asia Society's Southern California Center reported on China for the Far Eastern Economic Review and the Wall Street Journal; May Lee reported on China and other parts of Asia for CNN, CNBC and the Asian Wall Street Journal, more recently she's reported from Los Angeles for CGTV.

Book interview with Scott Tong, A Village with My Name: A Family History of China’s Opening to the World, 2018

Now reporting from Washington, D.C., Scott Tong was Marketplace Radio's Shanghai correspondent from 2006-2010. During that time, Tong began research into his family's complicated stories which revealed a great deal about how people experienced China's tumultuous history from the late 19th century through civil war and invasion in the 20th century to the rejoining the global economy in the 21st. (Click here for his more extended talk.)

David Pierson, 2019 (USCI | YouTube)

David Pierson was a Beijing-based Los Angeles Times correspondent from 2009 to 2013. One of the first stories he covered was the aftermath of riots in Xinjiang, but much of what he covered was the rapid rise of the Chinese economy. He is now the Singapore bureau chief for the Times.

David Barboza, 2020 (USCI | YouTube)

After his reporting on the fortune of Wen Jiabao's family earned him a Pulitzer Prize, David Barboza continued working in China. He eventually left the New York Times, however, to launch The Wire China, a digital magazine and data company focusing on China's rise. He discussed a variety of topics, including covering China from afar. Barboza speaks about the Wen exposé in "Follow the Money."

Lingling Wei and Bob Davis, 2020 (USCI | YouTube)

Wei and Davis reported from Beijing for the Wall Street Journal. They continued to collaborate after Davis returned to the United States. Wei was among those reporters forced to leave China in 2020 as the U.S. and China engaged in tit-for-tat expulsions of each other's journalists. Wei and Davis joined us to discuss their inside look at the U.S.-China trade war: Superpower Showdown.

2022 Updates on "Chito" Romana and Joseph Kahn.

Romana became the Philippines ambassador to Beijing and Joseph Kahn takes over as executive editor of the New York Times.