English | 中文

"The biggest irony is that while many foreign reporters in Peking cannot wait to get out, the Americans are vainly battering at the gates to get in."

-- David Bonovia, TImes of London correspondent, 1975

This episode focuses on the period between U.S. President Richard Nixon’s 1972 trip to China and the fall of the Gang of Four in October 1976. While the U.S. established a liaison office in Beijing, the lack of formal diplomatic relations meant that American reporters could not be based in China. Most reporting continued to be of the China-watching variety, though each of the major broadcast networks was permitted to shoot a documentary in China and many reporters gained access for short visits. It was a tumultuous period, the last year of which included the death of three of China’s revolutionary giants, a natural disaster which took a quarter of a million lives, and fierce battles over who would run China after the Mao-era.

This video is also available on the USCI YouTube Channel.

The documentaries prepared by the networks offered a much richer look at China than had been possible previously. CBS focused, for example, on Shanghai and ABC on “the people of People’s China.” One journalist managed, as part of a left-wing group, to get to work at various sites in China, including Dazhai, the model commune. Others visited to cover the trips of American leaders including Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and President Gerald Ford. During the latter’s visit, one of Chairman Mao’s translators, Nancy Tang, sparked the imagination of cartoonist Gary Trudeau who turned her into the character “Honey” in his Doonesbury strip. The political strains of the era were felt by all. One especially interesting story involves a return visit thirty-years later to re-interview a teacher who was terrified of her students.

During this period, several of the Hong Kong-based China watchers reported on political struggles among China’s leaders. Deng Xiaoping reappeared on the scene, only to be purged again. Mao welcomed Nixon back to China in 1976, but the Chairman, along with Premier Zhou Enlai, exited the stage in 1976. Jiang Qing, Mao’s widow, and her associates moved to consolidate power, but the episode ends with them in prison and a giant propaganda campaign to condemn them.

Interviewees in this segment (and the organizations they represented for during this period)

Steve Bell, ABC

Richard Bernstein, Time Magazine

Henry Bradsher, Washington Star

Tom Brokaw, NBC

Raymond Burghardt, U.S. Foreign Service

Fox Butterfield, New York Times

Frank Ching, New York Times

Mike Chinoy, CBS

Irv Drasnin, CBS

Bruce Dunning, CBS

Robert Elegant, Los Angeles Times

Liu Heung-Shing, Associated Press

Bernard Kalb, CBS

Ted Koppel, ABC

Joseph Lelyveld, New York Times

Jay Matthews, Washington Post

Ron Nessen, Ford White House

J. Stapleton Roy, U.S. Foreign Service

Jerrold Schector, Time Magazine

Orville Schell, The New Yorker

Barbara Walters, NBC

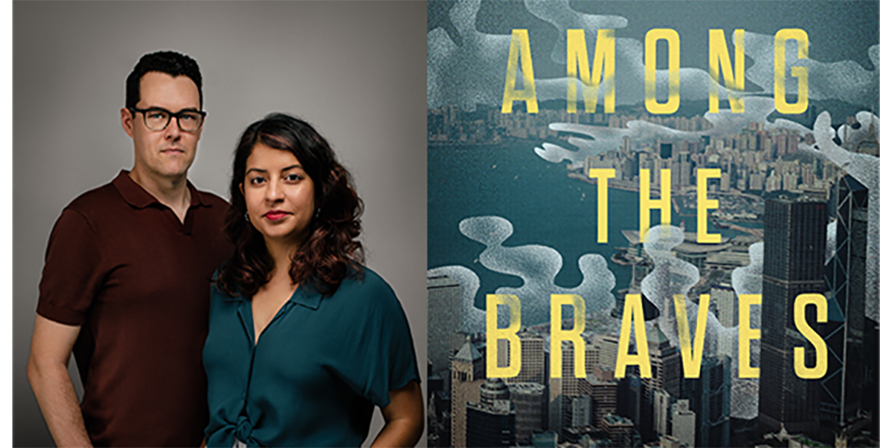

A major initiative of the USC U.S.-China Institute, Assignment:China is a ten part series focusing on the work of journalists for American news organizations in China. The series begins with the civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists and ends with journalists today covering a much more prosperous, but no less complicated and diverse country. Mike Chinoy writes and narrates the series. Craig Stubing is the series editor and lead videographer. Clayton Dube conceived of the project and oversees it.

Assignment: China is possible only due to the generous support of donors. The series is dedicated to the memory of John Rich, a longtime newsman who accompanied the American ping pong team to China in 1971. Our supporters include Ming Hsu and Nate Rich as well as Stephen Lesser, the U.S. State Department, and the Turner Foundation. We welcome you to join this effort by making a tax deductible contribution to the USC U.S.-China Institute.