|

Nixon wanted substantive talks behind closed doors and great pictures for the folks back home. TV Guide cover, Feb. 19-26, 1972.

|

On July 15, 1971 in Burbank, California U.S. President Richard M. Nixon announced that he was going to China (text, video). Few statements have raised as many questions as that one. Nixon, the stern cold warrior, was reaching out to the largest communist country. Those who had been listening carefully to Nixon, however, knew that he had long wanted to forge ties with China. Even before he became president he had written of this and from the first days of his presidency he had sought to establish contact with Beijing's

| Other USC U.S.-China Institute Resources |

Assignment: China "The Week that Changed the World" -- documentary featuring interviews with the journalists who covered the Nixon trip and the officials who sought to shape that coverage. The documentary features archival broadcast reports as well as never before released footage and still images. |

Getting to Beijing: Henry Kissinger's Secret 1971 Trip -- annotated chronology/documents related to opening talks between China and the United States. |

| Symposium on "The Week that Changed the World" -- presentations by Nixon administration officials on "the inside story" on how the Nixon White House sought to manage the visit and comments on the state of U.S.-China relations today (website | YouTube). |

| U.S.- China documents -- government reports, speeches, treaties, and other materials |

leaders. We earlier documented these efforts and the Chinese response to them in "Getting to Beijing: Henry Kissinger's Secret 1971 Trip."

The documents and recordings referenced below show the careful work that the President, National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, and many others put into trying to make the trip a success both in terms of what was accomplished in the discussions with Chinese leaders and in how the effort was received at home. Throughout the record, one finds Nixon commenting on press coverage and reminding staff to work to ensure that that great television images were transmitted back to the U.S.

Documents on Chinese preparations and the candid reactions of Chinese leaders are not available. We do, however, have an understanding of some of this through what was recorded in discussions Nixon and Kissinger had with Zhou Enlai and others and in what Nixon's staff and journalists picked up as they prepared for and covered the event.

Clayton Dube compiled and annotated these materials. Many institutions have helped make these valuable materials available, including the National Archives, the U.S. State Department Office of the Historian, the Richard M. Nixon Library and Museum, the Richard Nixon Foundation, the Gerald R. Ford Library, the National Security Archives at George Washington University, and the University of California, Santa Barbara American Presidency Project.

Nixon, of course, wanted this trip to be remembered as "the week that changed the world." He branded it as such in his final toast. Did it? Most concluded then and argue now that it did. It did not sweep away a generation of mistrust and serious differences, but it ushered in a period of dialogue that continues today. Thanks to this engagement, some core issues have been set aside and progress on a number of others has been possible. It may have also changed the geopolitical environment enough to facilitate real progress in U.S.-Soviet arms talks. The opening may have less directly and immediately aided those among China's leaders who wanted economic reform and greater engagement with the world.

The impact of the Nixon trip was so large and lasting, U.S.-China ties are so multifaceted and evolving, and China's role in the world so important and increasing that some might assume that Nixon and China's leaders were not taking much of a risk in reaching out to and welcoming each other. But this was far from clear back then.

It was also not certain, when Nixon left Washington on his journey, how he would be received in Beijing, on the final wording for the joint communiqué, and that the American public would endorse the effort. The worries and how they were resolved comes through in the exchanges summarized below.

In addition to focusing on the Nixon trip, the documents below include information about exchanges that happened immediately afterwards. These include the delivery of pandas to the National Zoo, a visit by the Chinese national ping pong team, and trips by Congressional leaders.

|  |  |

| The Nixon trip was shown live on major networks, dominated American and Chinese front pages, and was the cover story on major American news magazines: Newsweek, March 6, 1972, Life, March 3, 1972, and Time, March 6, 1972. | ||

Note: Apart from Nixon, Kissinger, Mao, and Zhou, the names of individuals are in bold when first introduced below.

Skip to the actual trip | Read the final communiqué issued by the two sides

April 14, 1971

The American ping pong team was in China and generating headlines. Chuck Colson, a White House aide, spoke with the president. Nixon worried, “That [his China initiative] doesn’t help us with folks. I think what we gotta realize … We polled all this, you know. People are against Communist China period. They are against communist period.” Colson tells Nixon engagement with China won’t help the administration with middle America, but could help with young people. Colson noted that Harry K. Smith’s television commentary discussed it and credited Nixon’s 1967 Foreign Affairs article. Smith noted that the ping pong opening was the product of his signal. (Click here to listen.)

July 19, 1971

H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, Nixon’s Chief of Staff, took notes on a meeting the President had with Henry Kissinger. Nixon suggested that in his meetings with the press, Kissinger could note that the President was “uniquely prepared for this meeting” and shared admirable characteristics (philosophically-minded, unflappability, taking a long view, and tough) with Zhou Enlai. (Isaacson, Kissinger, A Biography, 2005: 350-51) Haldeman's former home in the Hancock Park section of Los Angeles is now the residence of the PRC Consul General.

July 20, 1971

Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs U. Alexis Johnson sent Kissinger a memo outlining the Japanese government's reaction to Nixon's announcement that he was going to China. Johnson had spoken with Japan's Ambassador to the U.S. Ushiba Nobuhiko (牛場 信彦). Ushiba began by expressing admiration for the ability of the President to take such a bold move. In Japan, a prime minister would have had to discuss the plan within his "party and cabinet with the inevitable leaks."

Ushiba worried, though, that since Japan's government had long stressed close foreign policy coordination with Washington, that it was now vulvernable to charges that the U.S. "had pulled the rug out" by not just not consulting with the Japanese, but not even informing them.

The Japanese now worried that Beijing wanted to split the U.S. and Japan. In addition, Ushiba warned that the opposition in Japan would take this lack of consultation as evidence that the U.S. was not a trustworthy partner in other matters, including the removal of nuclear weapons from Okinawa. (Click here to read this letter.)

August 16, 1971

Kissinger met in Paris with China’s Ambassador to France, Huang Zhen 黄镇. Kissinger proposed either February 21 or March 16, 1972 as the date of Nixon’s visit and tells him that February 21 is the preferred date. Kissinger also told the ambassador about ongoing talks with the Soviets on nuclear weapons and that while the administration did not favor the creation of an independent Bangladesh, but that the Democrats in Congress were “completely on the side of Indian propaganda.” He said that the U.S. would understand if other countries provided Pakistan with military aid. (Click here to read the document.)

August 17, 1971

Kissinger reported to Nixon on a meeting he'd held with Soviet Ambassador Anatoliy Dobryin. Dobryin asked if there were problems with the planned Nixon trip to China. If not, why hadn't the dates been announced yet? He also expressed worries that the entire venture was aimed at the Soviet Union. Dobryin also asked if the U.S. was planning to support China in any armed struggle that country might have with India. Kissinger declined to respond. Kissinger suggested announcing the US-USSR summit in September, with the trip to start on May 22, 1972. (Click here to read the document.)

September 14, 1971

Nixon called White House H.R. Haldeman in the evening to complain that Chief of Staff Henry Kissinger suggested Nixon give an interview with the New York Times about China. Nixon was upset and told Haldeman that no one in the White House was to talk with the New York Times. Nixon is outraged that Kissinger even raised the question. Nixon said, however, that he was open to doing interviews with television reporters. (Click here to listen.)

University of Southern California alum and Los Angeles attorney Harned Pettus Hoose wrote to General Alexander Haig, Kissinger's deputy, to offer a detailed advice on what the President and Kissinger needed to know for their spring trip to China. The son of missionary parents, Hoose grew up in China and later served as a U.S. Naval Officer there during World War II. Haig subsequently agreed to forward a detailed manual prepared by Hoose to Kissinger and to include Hoose among a select group of advisors. The briefing manual, a digital copy of which is available here (22mb), covered a wide variety of cultural and political topics and included suggestions for Nixon's speeches and toasts. In addition to the manual are Hoose's letters to Haig, Kissinger, and Nixon. He also offered to accompany the President to China.

Nixon and Kissinger, of course, were inundated with advice. Hoose's, however, seems to have been particularly welcome. John Holdridge went with Kissinger on his secret July 1971 trip, worked with him to craft the eventual Shanghai Communiqué, and served as deputy chief of mission at the U.S. liaison office in Beijing 1973-1975. This is what he wrote in his memoir, Crossing the Divide: An Insider's Account of the Normalization of U.S.-China Relations (1997, p. 78):

“Among all the outside advice we received I particularly valued one item: a neat loose leaf binder presented to me personally by a California businessman named Harned Hoose, who was the nephew of Dean Pettus, the pre-World War II head of the College of Chinese Studies in Beijing (then Peking). Hoose had spent a good part of his childhood until high school living with Dean Pettus, and he spoke fluent colloquial Chinese. He was able to contribute useful insights into traditional Chinese cultural traits and practices, which he carefully had catalogued and tabbed in his binder for our use.”

Hoose wrote that he prepared the materials in part because "renewed communication between us and the Chinese

people, in addition to serving our American interests and world peace by helping in the balances of power in Asia, also inevitably will help the great and likeable Chinese people to revert to and openly manifest their traditional character traits, and reject communism, probably initially in its present militant form, and eventually in its entirety. That does not mean that we want for the Chinese, or that they would accept, a return to their folorn days of warlordism, western encroachment inside their country .... But the Chinese people deserve far better than the rigid, grim, stultifying thought-control and militant suppressions now imposed upon them by the communists. One need only to read China's history and to know the underlying deep cultural strains of the Chinese people to know that they are capable of having and deserve to have a relatively benevolent government, allowing individuality and the other national traits to the people. Such a government and such a people can also be of value to us, in our national interests and in achieving long-range, secure and honorable peace in Asia and elsewhere in the world." After the nHoose visited China on behalf of a dozen U.S. companies in May 1972.

The Hoose Library features mosaics of major philosophers, including Confucius. Hoose's remarkable manual is held in the Nixon Library. Ken Klein of the USC East Asian Library prepared this digital edition, which is also available at the library website. Hoose later contributed a chapter on "How to Negotiate with the Chinese of the PRC" to a 1974 volume on Doing Business with China. One of Hoose's great uncles, James Harmon Hoose, was an influential professor at USC, 1902-15. The philosophy library is named for him.

October 13, 1971

Nixon and Haldeman discuss who could be part of the press contingent on the upcoming China trip. Nixon tells his chief of staff he doesn’t want to bring enemies on the trip. “This is one time we can be very hard-nosed.” (Click here to listen.)

October 17, 1971

Nixon talks with Secretary of State William Rogers about the upcoming United Nations vote to expel Taiwan. Nixon thinks there’s a chance to win the vote. Nixon says he can’t believe that Israel would vote against the U.S. on this issue. (Click here to listen.)

October 20, 1971

Kissinger led a number of Nixon aides, including Dwight Chapin, the Deputy Assistant to the President, to meet with Zhou and others, including Ye Jianying, vice-chair of the Chinese Communist Party's Central Military Commission. Zhou commented on how young the 30 year old Chapin looked (click here for Chapin's remembrances of the preparations). The purpose of the meeting was to plan Nixon's trip, but it also included. It began though with both sides reassuring each other that they recognized the stakes involved.

Zhou began by noting that Kissinger had expressed interest in meeting John S. Service, a former U.S. Foreign Service officer who had been based in China and reported on the Communists during World War II and the Chinese Civil War. Service and a few other Americans had recently met with Zhou.

Zhou said to the others, "Our relations with the United States have been cut off for a long time. The previous visit of Dr. Kissinger has made an unofficial beginning and, to say the least, it shook the world a bit."

Kissinger told Zhou, "The President has asked me to reaffirm in the strongest terms his personal commitment to the improvement of relations between our countries for the sake of our two peoples and for the sake of the peoples of the world. We have received much unasked-for advice from other countries, especially one other country in recent months, pointing out the physical limitations of China's power. Our policy is not based on such considerations. It is produced by profound convictions and not by an attempt to create a power combination." He continued, "we believe that the People's Republic and the United States have many congruent interests. It is no accident that our two countries have such a long history of friendship. We believe that peace in Asia and peace in the world requires your full participation. We will not participate in arrangements that affect your interest without involving you."

Kissinger emphasized that Nixon was taking a political risk by coming and that some within the government were opposed. Zhou indicated that some in China were also opposed and that it was difficult sometimes to move bureaucrats in a new direction.

With regard to the logistical matters of the visit, Kissinger cautioned, "China, despite its long experience in handling outsiders, has never undergone anything like the phenomenon of a visit by an American President." Kissinger then explained that Nixon's assistants had developed a book with details about what the visit would require. Central in this area were the telecommunications requirements. Kissinger told a doubtful Zhou that even when travelling the president had to have "reliable, rapid, and secure communications" because only the president can make some decisions (especially those relating to the use of nuclear weapons).

Turning next to the matter of the press, Kissinger joked that the New York Times was "a sovereign country" (not underthe Nixon administration's control). He said, "I had never considered the question of the press, and when we talked in July I mentioned the figure of 10, I believe. When I asked our Press Secretary what the absolute minimum that was necessary for such a trip, he proposed a figure of 250." Kissinger said that two thousand press applications came in for the trip and that Press Secretary Ziegler had cut the number to 150. He noted that 450 reporters went with Nixon to Romania, 350 to Yugoslavia, and 400 to 500 to Britain.

Kissinger and his assistant Winston Lord play ping pong, October 1971.

Zhou then turned to the key issues to be addressed during the Nixon visit. The first was the obstacle that the Taiwan issue posed to establishing normal diplomatic relations. Other issues included the war in Vietnam, instability on the Korean peninsula, and relations with Japan.

Kissinger proposed February 21 or March 16, 1972 for the visit. Zhou responded that his government favored February 21. The two sides ended by stressing they both wanted peaceful relations with the Soviet Union and that the purpose of the U.S.-China dialogue was to establish ties, not to align against the Soviets. (Click here to read the transcript.)

October 25, 1971

The United Nations General Assembly voted to expel Chiang Kai-shek’s government and to seat representatives from Beijing. The People’s Republic of China was to also replace Republic of China (the resolution used Chiang Kai-shek rather than ROC) in all UN organizations.

An earlier resolution pushed by the United States (no. 1668) required a two-thirds majority vote to change China’s representation. Taiwan’s representatives walked out ahead of the vote. The United States voted against the resolution, having unsuccessfully sought to have both governments represented in the UN. (Click here to see the resolution and the voting break down: For - 76, Against - 35, Abstain - 17, Absent - 3).

October 26, 1971

California Governor Ronald Reagan called Nixon to talk about the UN decision to expel Taiwan. Nixon complained about Iran’s vote in favor of the resolution. Reagan called on Nixon to stop participating in the UN, not to withdraw, but to simply not vote or be bound by any vote.

January 7, 1972

Haig, a Kissinger aide, and Dwight Chapin, a Nixon aide, met with Zhou Enlai at just before midnight. Zhou began the discussion by noting that his assistants had drunk quite a lot with Haig and Chapin. Zhou went on to outline the Chinese positions on several matters. He first argued that the Soviets were, as they expected, working to sabotage the China-U.S. talks. He then noted that China would continue to provide material support to Pakistan in its struggle with India. Zhou condemned the U.S. Christmas bombing of North Vietnam and said it negatively affected the climate of U.S.-China talks. Later in the conversation, Zhou added that Dwight Eisenhower, the Republican, had ended the Korean war that Harry Truman, the Democrat, had started. He hoped that Nixon would quickly withdraw from Vietnam.

The big issue, however, was Taiwan. Zhou indicated he understood that some in America were opposed to normalization of relations with Beijing. He said that yielding to those forces would be a mistake.

Zhou further said he appreciated the American side raising the question of trade and that China would consider adding a passage on trade to the communiqué under discussion. Without normalization, though, Zhou said progress on trade would be slow.

Haig was at pains to emphasize that Nixon was not concerned with his public image. Haig emphasized that Nixon’s policies were not driven by public opinion. Zhou pointed out that they had invited the President and would treat him well, but that since the U.S. continued to recognize Taiwan, the treatment would necessarily be a bit different than if the U.S. and China enjoyed full diplomatic relations. (Click here to read the transcript.)

January 11, 1972

Kissinger called Nixon at the White House to discuss progress he and his team were making on the president's annual report to Congress on foreign policy and to discuss how the Soviet Union was reacting to Nixon's upcoming trip to China. Kissinger told Nixon that the Soviets were pushing the North Vietnamese to be more aggressive in the coming weeks so as to "overshadow your trip to Peking" and "I have no doubt, Mr. President [that] they are going to try to embarrass us at the Peking summit." Kissinger explained that he thought the Soviets were mainly taking aim at China, trying to discredit China's leaders. (Click here to listen.)

January 26, 1972

Talking with Dutch Prime Minister Barend Biesheuvel and J. William Middendorf, US Ambassador to the Netherlands , Nixon said that the Chinese knew the upcoming talks would not yield formal diplomatic relations. What he was hoping for was fostering communication so as to reduce the danger of confrontation. He thought this would be even more important “when they become a superpower, a nuclear superpower.” No Asia peace arrangement was possible, he said, without the “750 million Chinese… It’s just as cold-blooded as that.”

Nixon insisted he knew that there were large and important differences in how the U.S. and China saw things, but “where you’ve got the nuclear thing hanging in the balance,” you have to “talk, get along.” (Click here to listen.)

February 1972

The President’s chief advance man, Ron Walker, was sent to Beijing to work with the Chinese authorities to prepare for the visit. He had 100 others with him. As Walker says, “It was the only time that I ever set up a presidential event or presidential advance without knowing the outcome…. Whether the trip was domestic or international, a set of criteria would have been determined so that the objectives which need to be accomplished were clear.”

The only secure place for the President to talk was the car the Secret Service had flown in. The Chinese wouldn’t permit Nixon to ride in the car with Zhou Enlai, so it was mainly kept parked at the guest house and the President used it for secure calls to the United States. This trip was the first time a U.S. president ever flew on a non-U.S. airplane. (Walker and Anne Collins Walker in Thompson, ed., China, Taiwan, Japan, the United States, and the World (1998, p. 55.)

February 4, 1972

Nixon aide Chapin sent a memorandum to those who would be traveling to China with President Richard Nixon. It said, in its entirety,

“Throughout China you will find sayings from Chairman Mao. Many of the Chairman’s sayings center around ‘practice’.

“Borrowing from the Chairman the old ‘Practice makes perfect’, I suggest you become acquainted with using the enclosed chopsticks.” (Click here to see the memo.)

February 5, 1972

“Your meetings with the Chinese will be totally unlike any other experience you have had,” was how Kissinger opened a memo he wrote for Nixon and titled “Your Encounter with the Chinese.” The memo has a pep talk feel to it.

“The drama and color of this state visit will surpass all your others.”

“The conversations you will be at a far greater intensity and length than any previous diplomatic talks you have conducted.”

“You and your party will be superbly treated and will have to resist being seduced by the charm of the hosts. They are, in short, Chinese as well as (or despite) being communists.

“These people are both fanatic and pragmatic. They are tough ideologues who totally disagree with us on where the world is going. At the same time, they are hard realists who calculate they need us because of a threatening Soviet Union, a resurgent Japan, and a potentially independent Taiwan.”

Kissinger said that while the Chinese think time is on their side, in fact it is on America’s. He argued that Mao and Zhou were in their seventies and anxious to provide security for their government and country. Also, he thinks that Lin Biao’s challenge made Mao and Zhou think they needed the meeting with Nixon to yield immediate benefits.Nixon, Kissinger wrote, needed to impress his hosts with a comprehensive strategic vision and a plan to realize it that seems workable. Once agreement is reached on big concerns, Kissinger felt, the Chinese tend to be flexible on specific details. He advised being candid on where the U.S. and China disagree, but reminded Nixon that it was necessary to demonstrate that he understood their views, even if he didn’t agree with them.

Kissinger thought Nixon would enjoy talking with Zhou. In Kissinger’s words, Zhou was, with France’s Charles DeGaulle (a Nixon hero), the greatest statesman he had ever met. Kissinger wrote, “Zhou was an actor briefly in his youth and he probably still is.” Nixon should expect Zhou to offer a tough line occasionally and Nixon needed to respond firmly, but Zhou would also sometimes approach an issue in an indirect fashion.

“The only time I really have seen him display anger was when he was talking about Dulles’ ‘dirty trick’ in breaking the 1954 Geneva Accords (he has also been piqued ever since then that Dulles refused to shake his hand).” Nixon, of course, made sure to have his hand outstretched as he came down the ramp in Shanghai.

Mao, Kissinger stressed, was very much in charge, but would be unlikely to get into any details. Kissinger reported that Zhou only criticized the American first draft of the communiqué after discussing it with Mao. As a result, the working draft of the communiqué was more concrete about differences and objectives than is the diplomatic norm. Kissinger wrote, “Mao was not only authoritative, he was wise." (Click here to read the memo.)

February 9, 1972

President Nixon sent Congress his annual report on foreign policy. In a section entitled "The Journey to Peking," he began:"The record of the past three years illustrates that reality, not sentimentality, has led to my journey. And reality will shape the future of our relations.

"I go to Peking without illusions. But I go nevertheless committed to the improvement of relations between our two countries, for the sake of our two peoples and the people of the world. The course we and the Chinese have chosen has been produced by conviction, not by personalities or the prospect of tactical gains....

"The trip to Peking is not an end in itself but the launching of a process. The historic significance of this journey lies beyond whatever formal understandings we might reach. We are talking at last. We are meeting as equals. A prominent feature of the postwar landscape will be changed. At the highest level we will close one chapter and see whether we can begin writing a new one." (Click here to read this section of the report.)

February 14, 1972

In a phone conversation, Kissinger and Nixon discussed their talk and dinner with French writer André Malraux. Nixon said that when Malraux was leaving, he said that “your trip can change things for the whole future of the world.” Nixon went on to say, “I once said when I lived in the West and went to school with Chinese, I’m a little more Chinese than many Americans. It’s really true, you know.”

Kissinger says the Chinese are meeting “because they are the most threatened country in the world.” (Click here to listen.)

|

| Mao Zedong greets Richard Nixon (White House photo) |

|

|

|

| Air Force One, Nixon meets Zhou, Nixon and Zhou review the People's Liberation Army troops (White House photos) |

Air Force One brought Nixon and his delegation to Shanghai (click here to see the official itinerary of the visit). There he extended his hand for the famous handshake with Zhou. The two subsequently flew to Beijing aboard a Chinese jet. Not long after landing, Nixon, Kissinger, and Lord were hustled off for a meeting with an unscheduled but much appreciated meeting with Mao and Zhou.

Famously, Mao told Nixon that he liked rightists and Nixon responded, “those on the right can do what those on the left talk about.” Kissinger noted that some in the U.S. opposed Nixon’s trip and Mao responded that there was “a reactionary group which is opposed to our contact with you. The result was that they got on an airplane and fled abroad,” a reference to Lin Biao and his associates. Nixon told Mao that these conversations will be kept in strict confidence.The two leaders agree that the danger of war between the U.S. and China is relatively small, especially, Mao noted, if the U.S. withdrew troops from the region as planned. Mao went on to say that it was good to facilitate exchanges and to address smaller questions, even if large ones were not yet resolved. Mao also said that it was okay if the meetings did not at first yield agreement. (Click here to read the transcript.)

News Coverage

The People's Daily (人民日报) and other Chinese newspapers did not highlight the visit in the days leading up to Nixon's arrival. Short notes appeared on the front pages. Red Flag (红旗), a Communist Party journal, highlighted a 1940 article by Mao on the need for a united front against the threat posed by Japan. Readers could infer that the struggle against the Soviet Union might also require cooperating with less than ideal forces. In the U.S., of course, the print and broadcast coverage was overwhelming. The New York Times reported that "Sunday night at 10:30, American television viewers will be able to watch President Nixon set foot on mainland China. It will be the most historic and most technically complex live television event since astronauts first set foot on the moon" (Feb. 18, 1972).

Once Nixon had arrived and met with Mao, however, the Chinese press sent powerful signals to the public. Below are front pages from the New York Times and the People's Daily.

|  |

| Part of the front page of the New York Times, Feb. 21, 1972 | Front page of the People's Daily, Feb. 22, 1972 |

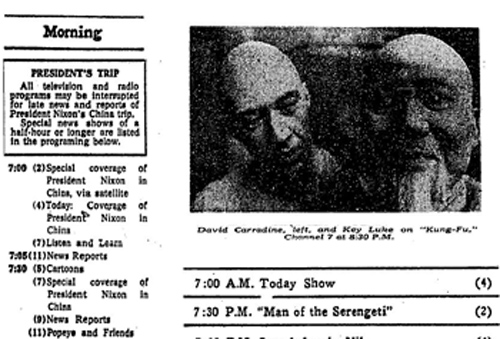

Some sense of how events were timed for an American breakfast audience can be seen from the New York Times television page below. Note the ABC's "Movie of the Week" for February 22, 1972: "Kung-Fu" (Trailer).

|

| Part of the New York Times television page for Feb. 22, 1972 |

February 22, 1972

Nixon’s delight in the imagery of the visit comes through with his first comments to Zhou Enlai. He tells of talking with one of his daughters back in the U.S. and hearing that the welcoming banquet the night before had featured on the morning news shows. He told Zhou, “My tipping glasses with the guests and going around the tables also made a very great impression” and that “[M]ore people than at any time in the history of the world heard our two speeches live.”

Nixon promised Zhou that only a few people saw the transcripts from Kissinger's visits and that only a "sanitized" version was shared with State Department officials such as Secretary of State William Rogers and Marshall Green, the top specialist on East Asia. He explained that while he did not mean to suggest Rogers and Green weren't trustworthy,“[O]ur State Department leaks like a sieve.” Nixon asserts that he intends to keep the record of his discussions with Mao and Zhou a closely held secret as well. Nixon expressed admiration for the way Zhou's government has maintained secrecy over the content of their discussions.

After this, Nixon laid out the principles to which he had agreed. "Principle one. There is one China, and Taiwan is a part of China. There will be no more statements made -- if I can control our bureaucracy -- to the effect that the status of Taiwan is undetermined." He then pledged not to support any Taiwan independence movement and to discourage the Japanese from supporting any independence movement. Any peaceful resolution worked out by China and Taiwan would be accepted by the U.S., Nixon said.

Nixon explained that he understood the Taiwan issue represented "a barrier to complete normalization" of relations between the U.S. and China, but said he hoped that progress could be made. He told Zhou that most of the American forces on Taiwan were supporting operations in Southeast Asia. They will be removed, he said, as the war in Southeast Asia is wound down. Nixon explained, though, that he didn't feel politically able to say these things publicly. He warned that there were opponents to his opening to China on both the left and the right.

"The left wants this trip to fail, not because of Taiwan but because of the Soviet Union. And the right, for deeply principled ideological reasons, believe that no concessions at all should be made regarding Taiwan." Two other groups, supporters of India and Japan, Nixon and Kissinger note, also oppose the warming of ties between the U.S. and China. Nixon said he understands this is a highly emotional issue for Zhou and his people. The trick, Nixon suggested, was to find language that meets the sensitive political needs on both sides.

Nixon insisted that while he understood the ideology behind Mao and Zhou's labelling the U.S. as an imperialist power, he thought that China's interests as well as America's mandated a continued military presence in Europe, Japan, and the Pacific. Nixon suggested that the Soviet threat was growing and that the threat to China was significant. He went on to say, "The U.S. can get out of Japanese waters, but others will fish there." He explained that the U.S. presence meant that Japan did not feel compelled to develop its own military.

In response, Zhou argued the U.S. was still dealing with the results of having backed the Kuomintang. He reminded Nixon that in a campaign statement Nixon in the 1950s said, "the Truman Administration lost a country of 600 million." Zhou argued that it was only the U.S. that kept Taiwan and China apart. He complained about the pro-Taiwan lobby's influence in the U.S. Zhou further argued that the U.S.-Soviet arms race helps no one and leads to greater danger.

Zhou further pushed Nixon to, if he really intended to withdraw from Southeast Asia, to take bold action and leave. Heargued that the U.S. had pushed for elections in Vietnam and then not lived up to its word. He said that as long as the U.S. pushes its allies in Southeast to fight, China will back its allies. Without matching deeds to words, Zhou said, you "facilitate the Soviets in furthering their influence [among non-aligned states]."

The Nixons joined Jiang Qing (江青Mao's wife) and Zhou at a performance of The Red Detachment of Women on the evening of Feb. 22. (White House photo)

Nixon responded by saying, "If ... we could negotiate a ceasefire and the return of our prisoners, all Americans would be withdrawn from Vietnam six months from that day." He then said that the North Vietnamese had been told this for months, but the North Vietnamese had to accept that the U.S. would not impose a political solution on the South. Zhou challenged this, saying "[Y]ou don't want to cast aside old friends. But you have already cast aside many old friends. Of these, some might be good friends and some might be bad friends, but you should choose your friends carefully." (Click here to see the document.)

February 23, 1972

In the morning Kissinger met with Ye Jianying (叶剑英), Vice Chair of the Central Military Commission, and Qiao Guanhua (乔冠华), Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs. Kissinger began by suggesting changes in the Taiwan section of the communiqué to emphasize the U.S. hoped Taiwan and China would work out their differences through bilateral talks and that the U.S. planned for the “progressive removal” of its forces on Taiwan.

Kissinger then went on to explain that, in December, he and Nixon thought the Chinese were going to intervene in the Indo-Pakistani war. Kissinger told the Chinese that if they had intervened and if the Soviets then attacked China, that the U.S. would have acted to help China. He said, “You had not requested this, and we did not do this for you, but for ourselves.” He further invited the Chinese to set up a channel by which they could raise intelligence-related questions. And then he began providing information on Soviet military deployments and armaments.

Near the end of the meeting, Qiao interrupted. He said that during Haig’s last visit, he said that the U.S. wanted to include a few words about trade in the communiqué. Qiao said, though, that the Chinese side was confused because Secretary of State Rogers had met and didn’t seem very interested in trade. Kissinger responded, “We would like to mention it in the communiqué and are prepared to discuss it. The difficulty is that not all of our people are familiar with every communication which has gone to you….” Qiao and Kissinger agree that Nixon and Kissinger will show Rogers the communiqué in a few days when the group goes to Hangzhou. (Click here to see the transcript.)

In the afternoon, Nixon met with Zhou. Chinese worries over India came through from the start. Zhou said that Indian Prime Minister Nehru coveted Tibet. He also blamed deposed Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev for the 1962 India-China war and both leaders hoped the Pakistani government would treat former President Yahya well. (Yahya helped facilitate the 1971 Kissinger trip.)

Zhou and Nixon talk about the importance of being bold. Zhou went on to say that he’s been monitoring the American press reports of the visit as well. He said, “Last night I received all the news reports from your country on your visit. I found that all views I saw were favorable, even Meany of the AFL-CIO supported you.” Nixon said he hoped Zhou would welcome Congressional leaders to visit. Zhou agreed, noting that the Chinese had followed the administration's request that they not meet with any American leaders ahead of the President. Nixon is thankful and he and Kissinger say that while Mike Mansfield, Senate Democratic leader, could keep a confidence, Hugh Scott, the Senate Republican leader, was a leaker.

Nixon pushed Zhou, though, to not welcome presidential candidates, just the two Senate leaders. Zhou concured, “Yes, they try to seize an opportunity. In your dining room upstairs we also have a poem by Chairman Mao in his calligraphy about Lushan mountain, the last sentence of which reads "the beauty lies at the top of the rnountain." You have also risked something to come to China. There is another Chinese poem which reads: "On perilous peaks dwells beauty in its infinite variety." Nixon said, "We are at the top of the mountain now," which generated laughter among the Chinese.

Zhou said, “We also hope not only that the President continues in office but that your adviser and assistants continue in office.” Nixon responded by offering his assurance that he plans to keep Kissinger around.

Nixon said that both sides must restrain their Korean allies. He says that it was he who told Syngman Rhee that he would not be supported if he attacked the North. Nixon said, “The Koreans, both the North and the South, are emotionally impulsive people. It is important that both of us exert influence to see that these impulses, and their belligerency, don't create incidents which would embarrass our two count1•ies, It would be silly, and unreasonable to have the Korean peninsula be the scene of a conflict between our two governments, It happened once, and it must never happen again, I think that with the Prime Minister and I working together we can prevent this.” Zhou says they should promote dialogue between North and South.

Zhou said that the Soviets are unhappy because they are expansionistic and the Chinese had called them on it. “Lenin talked about people who were socialist in words but imperialist in deeds. We began to give them this name when they invaded Czechoslovakia.”

Nixon and Zhou discussed the recently deceased Edgar Snow and his important interview with Mao. Snow did not publish what had not been authorized. Nixon concluded, “He didn't want to embarrass you. That's very unusual for a journalist.” (Click here to read the document.)

February 24, 1972

While the Nixons, Rogers, and others visited the Great Wall and Ming Tombs, Kissinger met with Qiao Guanhua. According to his memoirs, Kissinger and Qiao were feeling time pressure to finalize the communiqué. He wrote, "each side pushed the other against the time limit to test whose resiliency was greater. Determination was masked by extreme affability. The best means of pressure available to each side was to pretend that there was no deadline" (White House Years, 1979). According to Kissinger, Qiao wanted the U.S. to simply "hope" for "a peaceful Taiwan solution" and to separately pledge to "reduce and finally withdraw" U.S. forces from Taiwan. Kissinger said that was unacceptable, because "American public opinion would never stand for it." Qiao rejected Kissinger's counter-offer which linked withdrawals of U.S. forces to the "premise" of a peaceful solution to the Taiwan question and a "reduction of tensions in the Far East." The U.S. wanted to tie the drawdown of U.S. forces to the war in Vietnam. Qiao rejected that.

The Nixons at the Great Wall (White House photo)

A little after 5 pm, Nixon and Zhou met again at the Great Hall of the People. The focus of the discussion was Taiwan and Vietnam. On Taiwan, Nixon made it clear that he planned to normalize relations with China during his hoped-for second term in office. He told Zhou, though, that he could not make a formal agreement, in public or in private, to remove U.S. forces from Taiwan or to end other defense ties to Taiwan. Such a deal would make him politically vulnerable. Nixon said,"Chairman Mao takes the long view, as I do. I don't mean 1, 000 years, nor do I mean ten years on this issue. But I think the Prime Minister should have in mind, and Chairman Mao should have in mind, that I have stated my goal is normalization. If I should win the election, I have five years to achieve it. I cannot, for the reasons just mentioned, now make a secret deal and shake hands and say that within the second term it will be done. If I did that, I would be at the mercy of the press if they asked the question. I don't want to say that....

"Now if someone asks me when I return, do you have a deal with the Prime Minister that you are going to withdraw all American forces from Taiwan, I will say "no. 11 But I am telling the Prime Minister that it is my plan, and as step-by-step I withdraw I can develop the support that I will need to get the approval from our Congress for that action."

Nixon went on to explain that not even all members of his delegation agreed with his plan and how it would be sidestepped in the joint communiqué, "We have to sell our people, Rogers and Green. That is our problem. That is Dr. Kissinger’s job.” This is said to have caused Zhou to laugh.

On Vietnam, Nixon emphasized that he intended to forge a peace settlement and to withdraw American troops. But he also told Zhou that bringing the North Vietnamese to the bargaining table might require military action. “I realize that the Prime Minister's government may have to react to what we do," said Nixon, indicating that he understood that China would likely condemn such action. Nixon worried that his opponents would note that China would not urge Vietnam to do anything in the communiqué, “Obviously what will be said, even with a skillful communique, is what the People's Republic of China wanted from us was movement on Taiwan and it got it; and what we wanted was help on Vietnam, and we got nothing."(Click here to read the "memorandum of conversation.")

February 25, 1972

The Nixons visited the Forbidden City in the morning. In the late afternoon, Nixon met with Zhou. Zhou proposed a short 15 minute meeting with the full delegation the next morning. Nixon was mindful that U.S. State Department officials were upset at being excluded from many meetings. He said that he’d prefer a half-hour meeting because, “It would make some of our people who have not had a chance to sit in on the private sessions feel that they have a part to play, too. We could also have some photos taken. “

Zhou then raised the matter of Sino-Soviet relations. He said that China would like to improve relations with the Soviet Union, but because of the massing of Soviet troops on China’s border, the Chinese government would not enter into negotiations with the Soviets. Zhou raised the possibility that the Soviets might be thinking of fomenting unrest in Xinjiang so as to split it off as had happened with Pakistan and Bangladesh. Nixon responded that the U.S. would not recognize such a new nation.

Zhou noted that the Soviets had highlighted that Nixon and his government now used “People’s Republic of China” rather than “Communist China” in announcements and speeches. Zhou thought it odd that the Soviets would be unhappy about this. Nixon responded, “I think they apparently welcomed an antagonistic relationship between the U.S. and the People’s Republic of China.” Nixon emphasized, “my principle is any nation can be a friend of the United States without being someone else’s enemy.”

Nixon closed the meeting by raising the question of John Downey, a CIA operative held in China for almost two decades. He noted that the earlier release of Richard Fecteau and Maryann Harbert “had a very good impact on our country.” Nixon told Zhou that Downey’s mother was 76 years old and not in good health. He asked if China could show compassion and release Downey. “It would have,” Nixon said, “an enormously good impression in the United States.” Zhou said that something might be possible, but that it would take some time. (Office of the Historian, U.S. State Department.)

John T. Downey and Richard G. Fecteau, CIA officers held in China from 1952 to 1971 (Fecteau) and 1973 (Downey). (Still from CIA film)

****

In the evening, the U.S. side hosted a banquet to honor Zhou. Nixon and Zhou both offered toasts, with Nixon speaking about the Great Wall:"As I walked along the Wall, I thought of the sacrifices that went into building it; I thought of what it showed about the determination of the Chinese people to retain their independence throughout their long history; I thought about the fact that the Wall tells us that China has a great history and that the people who built this wonder of the world also have a great future.

"The Great Wall is no longer a wall dividing China from the rest of the world, but it is a reminder of the fact that there are many walls still existing in the world which divide nations and peoples."Zhou noted that their talks had not melted away significant differences:

"There exist great differences of principle between our two sides. Through earnest and frank discussions a clearer knowledge of each other's positions and stands has been gained. This has been beneficial to both sides.

"The times are advancing and the world changing. We are deeply convinced that the strength of the people is powerful and that whatever zigzags and reverses there will be in the development of history, the general trend of the world is definitely towards light and not darkness." (Click here to read the toasts.)

February 26, 1972

Chinese photo of the official delegation and their hosts.

In a meeting at the Beijing Airport on their way to Hangzhou, Secretary Rogers praised Zhou and the other hosts for their hospitality. Zhou responded that the Chinese side was only doing what they should do. He then went on,

“I would believe that there are some places in which we have not done enough. I have found, for instance, a shortcoming that your press pointed out to us. For instance, for your visit to the Great Wall we did some preparation which we believe was necessary, and it was earnestly, honest. But it was quite unnecessary to put up a show in the Ming Tombs, because it was quite cold that day. Some people got some young children there to prettify the Tombs, and it was putting up a false appearance. Your press correspondents have pointed this out to us, and we admit that this was wrong. We do not want to cover up the mistake on this, of course, and we have criticized those who have done this.” (Click here to read the document. ABC's Ted Koppel discusses this report in USCI's Assignment:China "The Week that Changed the World" USCI website | YouTube)On the plane to Hangzhou, Rogers and other State Department officials were shown the communiqué and objected to parts of it. Kissinger wrote "Unfamiliar with the obstacles overcome, those not participating can indulge in setting up Utopian goals (which they would have urged be abandoned during the first day of the negotiation had they conducted it) and can contrast them with the document before them. Or they can nitpick at the result on stylistic grounds, pointing out telling nuances, brilliantly conceived, which the world was denied by their absence" Kissinger blamed Nixon for excluding State from the real negotiations. Nixon, he wrote, worried that State's complaints, however trivial might become known and aid those who would be critical of the trip (White House Years, 1979).

So, in Hangzhou Kissinger reopened negotiations with Vice Foreign Minister Qiao. In his memoir, Holdridge (Crossing the Divide, 1997, pp. 91-92) wrote that Kissinger and Qiao met for several hours after dinner in Hangzhou haggling over the language. Holdridge argued that while exhausting, there was good will in the room. His example of the easy nature with which the two sides spoke was that Kissinger expressed irritation during comments made by Zhang Wenjin. Zhang asked, "Do I bore you?" To which Kissinger replied, "You're never boring, Mr. Zhang, but sometimes you are a damned nuisance." Kissinger wrote that it was 2 am when the two sides agreed on the final wording fo rthe communiqué and discussed what would be said at the press briefing. Kissinger wrote that he wanted Qiao to know that while the communiqué didn't acknowledge the U.S. defense commitment to Taiwan, that he would do so orally. Kissinger wrote,"My news conference in the Industrial exhibition Center Banquet Hall in Shanghai was surely one of the most paradoxical events to take place on Chinese soil since the revolution. A foreign official explained that his country would continue to recognize a government which was the rival to that with which he had been negotiating, and would defend it with military force against his hosts. I reiterated the continued validity of the defense treaty by reaffirming the appropriate sections in the President’s foreign Policy Report published just weeks previously. And it is a measure of their wisdom that there was no Chinese reaction. Our hosts understood their priorities" (White House Years, 1979).

Nixon, Zhou, and a young friend (White House photo)

February 27, 1972

The Nixons and Zhou toured many locations in Shanghai. The most important event was the release of the joint communiqué that the two sides had been discussing for months and which was still being negotiated during the visit. The communiqué has proven to be a remarkably durable document. It allowed the two countries to state their differences, keep U.S. ties to Taiwan from impeding progress on other matters, and set in motion the dramatic expansion of exchange that characterizes the relationship today.

The communiqué noted that an important door had been opened: "The leaders of the People's Republic of China and the United States of America found it beneficial to have this opportunity, after so many years without contact, to present candidly to one another their views on a variety of issues."

The differences between the two sides were substantial, but "the two sides agreed that countries, regardless of their social systems, should conduct their relations on the principles of respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states, non-aggression against other states, non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. International disputes should be settled on this basis, without resorting to the use or threat of force." With an unspoken nod towards the Soviets, the two sides were "opposed to efforts by any other country or group of countries to establish ... hegemony."On Taiwan, the Chinese insisted that Taiwan was an integral part of China and that "the liberation of Taiwan is China's internal affair in which no other country has the right to interfere" and stated its opposition to "any activities which aim at the creation of 'one China, one Taiwan,' 'one China, two governments,', 'two Chinas,', an 'independent Taiwan' or advocate that 'the status of Taiwan remains to be determined.'" The U.S. stated, "all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China." Further, the U.S. called for "a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves." The U.S. pledged to remove its forces from Taiwan as "tension in the area diminishes."

The U.S. and China affirmed their interest in fostering exchanges, including trade, and working to bring about normal diplomatic relations. (Click here to read the communiqué.)

At a banquet that evening, Nixon and Zhang Chunqiao (one of Zhou's rivals and an associate of Mao's wife Jiang Qing, he and Jiang were given death sentences in 1980 as leaders of the "gang of four," those sentences were subsequently commuted) exchanged toasts. Nixon said, "The joint communiqué which we have issued today summarizes the results of our talks. That communiqué will make headlines around the world tomorrow. But what we have said in that communiqué is not nearly as important as what we will do in the years ahead to build a bridge across 16, 000 miles and 22 years of hostility which have divided us in the past." Without saying so explicitly, Nixon highlighted the core factor, shared desire to constrain the Soviet Union, that brought the U.S. and China together:

"To mention only one [point of agreement] that is particularly appropriate here in Shanghai, is the fact that this great city, over the past, has on many occasions been the victim of foreign aggression and foreign occupation. And we join the Chinese people, we the American people, in our dedication to this principle: That never again shall foreign domination, foreign occupation, be visited upon this city or any part of China or any independent country in this world."

In his response, Zhang talked about Shanghai's progress and the work that lay ahead in development. And he also affirmed China's determination to make its own way,"More heavy and arduous tasks still await us, and the working class and the people of the entire Shanghai municipality are continuing to work hard under the leadership of the Communist Party of China along the road charted by Chairman Mao Zedong, the road of maintaining independence and keeping the initiative in our own hands and relying on our own efforts." (Click here to read the toasts.)

Late that evening, Kissinger met with Qiao Guanhua. He provided additional information on Soviet military resources. He and Qiao also discussed the secret channel they would use through Huang Hua, China's ambassador to Canada. They would maintain an open (publicly-known) channel through Huang Zhen, the ambassador in Paris. The two agreed that they would not tell Rogers about the secret channel and would only tell him that the open channel was being considered. (Office of the Historian, U.S. State Department)

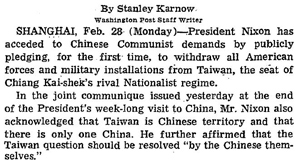

February 28, 1972

Nixon and Zhou held one last meeting before Nixon returned to the U.S. via Alaska. Nixon stressed the continuing importance of maintaining confidentiality and explained that he'd be meeting with various officials upon his return. Nixon asked that when differences emerge, as they were sure to do, that both sides use restrained rhetoric. They also confirmed that Senate leaders would be invited to visit. Zhou explained that the Chinese government wanted Nixon's initiatives on normalization to work and would be patient on resolving the Taiwan matter: "we being so big, have already let the Taiwan issue remain for 22 years, and can still afford to let it wait there for a time." (Office of the Historian, U.S. State Department)

Nixon spoke to members of his cabinet and the diplomatic corps upon his return. (Click here to read the speech.)

Back in the White House, Nixon spoke with Kissinger by phone. Kissinger told him that California Governor Ronald Reagan had called to ask that Nixon reaffirm U.S. support for its mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. Nixon blamed theWashington Post for stirring up trouble with conservatives (the Post had an article titled "Nixon Pledges Pullout of Forces in Taiwan" that day). Kissinger said he told Reagan that Nixon would do this and Nixon agreed. Kissinger then went on to say that Reagan thought the president had done a wonderful job, describing it as "one of the greatest weeks in the American presidency." Nixon asked Kissinger to make a statement supporting the administration's efforts on China.

Washington Post, Feb. 28, 1972

February 29, 1972

Nixon and Kissinger met with Senators Allen Ellender (D-Louisiana), Mike Mansfield (D-Montana), and J. William Fulbright (D-Arkansas) at the White House. Nixon complained that “rather naïve reporters” suggested that what brought us together is that, uh, well mainly, both China and the United States, the People’s Republic of China and the United States realized that we really didn’t have a, uh, that really that despite our philosophies we really weren’t all that far apart, and that if we’d just get to know each other better-that, uh, everything would be a lot better with each other. Not true at all.” Nixon explained that the main benefit is a reduction in the possibility of miscalculation on both sides, because “there will be talking and rather than … that inevitable road of suspicion and miscalculation, which could lead to war. A miscalculation which, incidentally, led to their intervention in Korea, which might have been avoided had there been this kind of contact at that time.”

“It was not our common beliefs which brought us together,” Nixon told the Senators, “[b]ut, frankly, our common interests and our common hopes. What are those common interests? One is the interests that both us have in maintaining our integrity and our independence. And second is the hope that each of us has to try to build a structure of peace in the Pacific, and going beyond that, in the world.” (Click here to listen.)

March 6, 1972

Nixon wrote to Rogers to mandate that State Department officers and other government officials "adopt a very restrained and disciplined approach in our on-or-off-the-record comments" on all matters relating to the developing relationship with China. Nixon specifically ordered Rogers to make sure that officials did not elaborate on the communiqué or on any of the meetings that were held. He did not want anyone to characterize the meetings or the trip in any way. (Office of the Historian, U.S. State Department)

March 13, 1972

In a call to Washington Star columnist Crosby Noyes, Nixon says he’s sending the pandas to the Washington Zoo rather than to San Diego or other places. “The problem, however, with pandas is that they don’t know how to mate. The only way they learn how is to watch other pandas mate.” As a result, the Chinese have kept the pandas for a few weeks to let the pandas observe others. They were due to arrive in April 1. (Click here to listen.)

First Lady Pat Nixon speaks at a ceremony opening the panda exhibit at the National Zoo. She later spoke with her husband by phone and he's pleased to hear that there was a lot of press attention at the ceremony.

| | |

| Pat Nixon accepts the gift of pandas on behalf of the United States. (Still images from White House film) |

April 17-18, 1972

On the 17th, Tricia Nixon Cox called her father to ask if there was anything special she should say at the ping pong match at the University of Maryland. She noted that the big protest worry is that Taiwan supporters will attend with flags.

He advises her that if asked, she should say that she’d like to go to China some day.

April 18, 1972: The President meets with members of the visiting Chinese ping pong team at the White House (White House photo)

The next day, she called him to tell him that she and Secretary of State Rogers had been roundly booed when they entered the arena. In addition, she said pro-Taiwan protestors had shouted "Down with Mao" and that caused the Chinese team to complain about the disrespect shown for Chairman Mao. Nixon spoke with Rogers who noted the booing, but also said he thought that young people liked the opening to China. (Click here, here, and here to listen.)

Establishing a custom that remains strong, the Chinese ping pong team visited Disneyland and Marineland in Southern California on April 26. The Associated Press quoted team leader Zhuang Zedong, "The ping pong ball is very light, but the friendship is very deep.... Sometimes we win or lose. This is temporary. Friendship is everlasting." (Zhuang spoke at USC in 2008. Click here to see his talk.)

April 19-22, 1972

Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Montana) and Minority Leader Hugh Scott (R-Pennsylvania) travelled to China at the invitation of China's government. Mansfield had served as a Marine in China in the early 1920s, studied and taught East Asian studies for a time, and was sent by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to China in the early 1940s. He may have met Zhou Enlai in Chongqing during that period. Mansfield became a senator in 1953 and first reached out to the Chinese government when Lyndon B. Johnson was president. A lawyer by training, Scott collected Chinese art and in 1967 published a book about Tang-era ceramics. In 1969, Mansfield had sent a letter to Zhou Enlai, via Cambodia's Prince Sihanouk, asking to visit China to seek a way forward for the two countries. At the time, Chinese leaders did not think it wise to welcome Mansfield.

According to Francis Valero, Mansfield's long-serving aid and Asia-specialist who went with him on the trip, the trip was "mostly ceremonial." The record shows that most of their meetings with Zhou and others focused on Southeast Asia. There was some discussion of scientific and cultural exchanges. (Click here to read the senators' report on the trip.)

Pfc. Mike Mansfield in China in the 1920s.

Like Nixon, the senators raised questions about Americans held by the Chinese (the story of two American prisoners, Central Intelligence Agency officers, was told in a 2010 film produced by the CIA, click here to watch Extraordinary Fidelity).

In a 1985 interview with a Senate historian, Valero said, "the Nixon trip was so decisive. Whatever you may think of Nixon, that was an extraordinary performance. He knew precisely how to do it in terms of the internal American situation. The use of the media, which I thought was outrageous at first, proved to be one of the most important and compelling factors in producing this changed attitude.” (Click here to read the interview.)

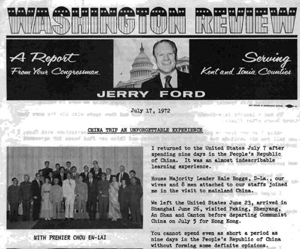

June 23 - July 7, 1972

House Majority Leader Hale Boggs (D-Louisiana) and Minority Leader Gerald Ford (R-Michigan) traveled to China. In a newsletter to constituents, Ford concluded, “Whatever we may think of the Communist Chi nese system, the fact remains that it is vital we live i n peace with the People 's Republic of China.

Ford newsletter, "China Trip An Unforgettable Experience," July 17, 1972

"Although there are wide philosophical differences between us and China, it is important that we normalize relations between the two countries .

"I believe our trip has helped promote understanding.”

In a private letter to President Nixon after meeting him, Boggs and Ford wrote, This report was given to President Nixon. It included the following:

"We realize we were shown only what they wanted us to see, and nearly all the places we visited had been meticulously prepared for our arrival (the environs were swept clean; the hosts carefully briefed on what to do and say; little children primed to undertake games and classroom activities as we arrived). But, of course, we do much the same for foreign officials visiting our country, so we are not critical in mentioning these preparations. Actually, they suggest the Chinese leadership goes to impress foreign visitors, including Americans, favorably. That may bode well for the effort you have so well begun to clear away unnecessary barriers to improved relations between our countries."

Click here to see the private letter and click here to see the formal report Boggs and Ford provided the House of Representatives. They entitled it "Impressions of the New China."

In the public report, the House leaders wrote, “We harbor no illusions that the path to that relationship will be easily or quickly traveled. There are many fundamental differences between our societies. Nevertheless, our visit reminded us again that people the world over share a common desire for friendship.” They were struck by the cleanliness of the cities and the absence of flies.

“The views expressed to us by Chinese leaders that China is today preoccupied with her massive internal problems, that she has no present notions of international conquest or expansion, that her present aspiration is only to develop peacefully-these views we find credible for today.

“We are therefore persuaded that, at present, the world has little to fear from China. On the other hand, from China's point of view, the world must be something of a threatening place.”

“.... In disciplined, unified China, American visitors will wonder if our self-indulgent free society will be able to compete effectively fifty years hence with this totalitarian State, possessed of a population which dwarfs our own, with equal or greater natural resources, and with total commitment to national goals.”

“... We did not find among our hosts the same high degree of enthusiasm for early and measurable increases in trade which has stimulated the interest of American businessmen. Indeed, in pursuing the matter of mutual contact generally, we at no point found the Chinese more reserved than in talks respecting bilateral trade.”