If people don't attack us, we will not attack them, if they attack us, we will surely attack them, 1970

Poster from the collection of Stefan R. Landsberger, Amsterdam.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get it delivered straight to your inbox!

Fifty years ago next week, U.S. President Richard Nixon went to Beijing, meeting Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai, ending two decades of U.S.-China hostility and launching a new era. Despite the many issues between the two countries, it is possible to imagine the American and Chinese governments going out of their way to commemorate the 1972 visit. But the pandemic has kept Xi Jinping at home for two years and, to protest human rights abuses in China, the White House initiated a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics. Those games end on Feb. 20, the day before the anniversary of Nixon’s arrival in Beijing. Earlier this week, the Chinese and Mexican governments exchanged greetings to mark the fiftieth anniversary of their formal diplomatic ties. Perhaps some similar exchange will acknowledge that week-long trip was an essential breakthrough for relations between the U.S. and China.

This week we look at the strategic considerations that brought Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong together. How did we go from killing each other in Korea at the start of the 1950s to toasting each other at banquets in the 1970s?

Nixon became a national figure as a fierce anti-communist. As a Senate newcomer, Nixon argued that the Truman’s withholding of aid to Chiang Kaishek’s government “lost China” to the Communists. At the outset of the Korean War, he’d advocated bombing targets inside China. In 1951 he criticized the idea of a negotiated end to the war, calling instead for “military victories and economic blockades.” Nixon helped General Dwight Eisenhower win the Republican nomination for president in 1952 and Eisenhower made him his running mate. His youth (39 when elected) balanced Eisenhower’s age (62).

Among Nixon's first assignments was a lengthy 1953 trip to Asia, including a stop to talk with Chiang Kaishek in Taipei. Nixon pushed the State Department to do all it could to publicize the tour and turn out big crowds. One big luncheon speech in Hong Kong was hosted by the Junior Chamber of Commerce and the Rotary Club. It was well-received despite tensions over the U.S. embargo towards China. Nixon’s hosts announced their next children’s library, in Yuen Long, would be named for the vice president. Nixon sent a telegram when it opened, writing “I can think of no factor more important to a free, independent, and prosperous Asia than the opportunity for the youth of Asia to learn the truth, untarnished by Communist propaganda."

Anxious to avoid being entangled in another war in Asia, Eisenhower hoped signals such as the 1955 Formosa Resolution (authorizing the U.S. president to defend Taiwan) would be a deterrent. The U.S. sent arms and advisors to Taiwan and Eisenhower himself visited in 1960. Taiwan withdrew from Dachen Islands 大陳, but retained Kinmen 金門 and Matsu 馬祖. China shelled the islands, initially as part of a campaign to recover them, but eventually to raise and relax tensions on its own schedule. Those islands and whether or not the U.S. needed to help defend them became a hot topic in the 1960 presidential debates between Nixon and Senator John Kennedy. Though Kennedy approximated Eisenhower’s own private assessment that Kinmen (Quemoy) and Matsu created a useless vulnerability, Nixon argued for their defense saying, “[W]hat do the Chinese Communists want? They don't want just Quemoy and Matsu; they don't want just Formosa; they want the world.”

Nixon narrowly lost the 1960 election, but continued cultivating established and rising Republican figures. He traveled extensively and paid attention to the changing geopolitical environment, becoming aware of the growing fissures between China and the Soviet Union and the strain that fighting in Vietnam imposed on the U.S. By late 1967, the U.S. had half a million troops in Vietnam. Nixon argued he had a secret plan to end the war and the U.S. needed to reach out to China. In a Foreign Affairs article that Mao read in Chinese translation, Nixon wrote "we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates, and threaten its neighbors. There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation." After Nixon won, Mao ordered his inaugural address be published in China.

Though Soviet support had been critical to the Chinese Communist triumph in the Civil War and the first years of the People’s Republic, Mao was never comfortable as a junior partner. The war in Korea was far costlier to China than it had been to the Soviet Union. It turned the U.S. into a staunch enemy, protecting Chiang-controlled Taiwan. Mao pushed against the idea of peaceful coexistence with the capitalist world. China began denouncing the Soviet Union as having become revisionist and failing the communist cause. The Soviets withdrew technical advisers from China. Beijing continued its criticism, finding fault with Moscow at every turn (e.g., Cuban missile standoff and nuclear test ban agreement). For its part, Moscow worried that China was a rival for potential allies in the developing world and that Beijing was needlessly provocative. And in 1968, Moscow sent tanks into Czechoslovakia.

Mao doesn’t seem to have actually feared Soviet attack, though China had for years relocated industry inland and dug tunnels and bomb shelters in major cities. As seen in the map above, in 1969, border skirmishes broke out at several places along China’s long border with the Soviet Union. In August, a top Soviet official in Washington asked a U.S. diplomat “point blank what the US would do if, the Soviet Union attacked and destroyed China's nuclear installations.” Ten days later, the U.S. CIA director told reporters that Moscow was asking foreign governments how they would respond to a preemptive attack on China. Mao loved mobilizing against foes, an effort that included propaganda posters like the one above.

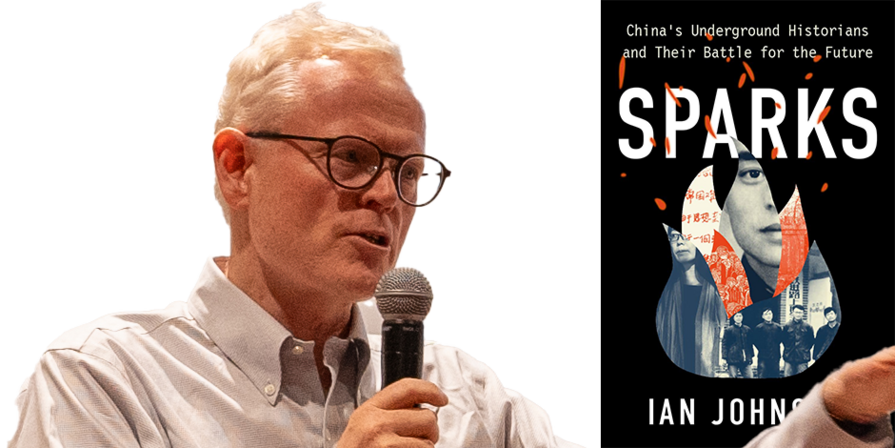

|

| "I'm not sure of the rules, but it looks like an interesting game." Hugh Haynie, Louisville Courier-Journal |

By this time the U.S. and Soviet Union had been locked into an arms race for a quarter century, building bombers, missiles and submarines to carry nuclear weapons (see the chart below). Nixon hoped to rein in the competition. For his part, Mao told his doctor, Li Zhisui, “Didn’t our ancestors counsel negotiating with faraway countries while fighting with those that are near?” Anxiety about the Soviet Union helped bring the U.S. and China together.

Despite the interest in both capitals, the two sides moved quietly and cautiously. In 1971, Pakistan helped orchestrate National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger’s secret trip to Beijing, which yielded the plan for Nixon to go to China. Both the U.S. and China insisted that the summit didn’t target third countries. But Washington and Beijing were both happy to give Moscow something to worry about. As their joint communiqué made clear, the U.S. and China remained at odds over many issues. Was Nixon right? Did that week in February 1972 change the world? We’ll pick that up next week.

In the meantime, please explore our documentaries and web resources on the U.S.-China rapprochement and please join our discussions next week with scholars and journalists about the visit, its consequences and the current state of U.S.-China ties.