Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get them delivered straight to your inbox!

On Wednesday, opposition lawmakers resigned as a group from Hong Kong's government. They withdrew to protest the expulsion from the Legislative Council of four members who had already been prohibited from seeking reelection. Beijing and Hong Kong's government judged those LegCo members guilty of favoring independence for Hong Kong. Wu Chi-wai, leader of the broader group, said the expulsion represented the centralization of all power, from Beijing through a "puppet" Hong Kong government. He declared, "today is the end of 'one country, two systems.'" Wu argued that Hong Kong no longer enjoyed a separate system of government.

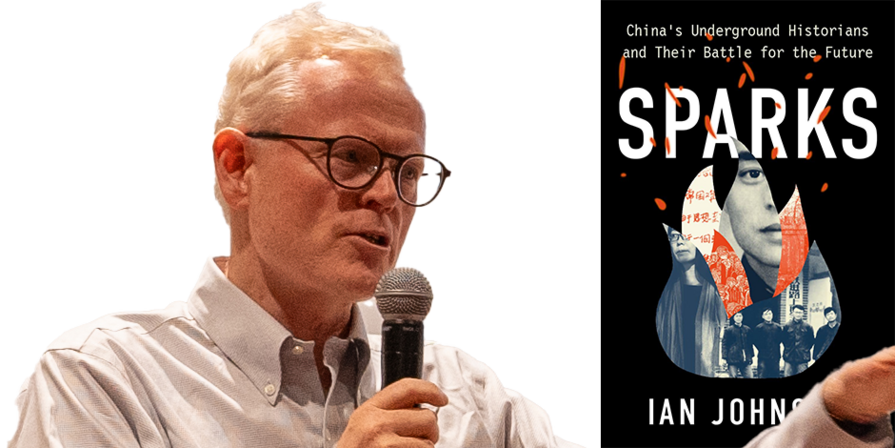

On November 12th, we hosted an online discussion with Michael Davis, longtime law professor in Hong Kong and the author of the just released book Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law. You can watch a recording of that converastion here.

In the 1984 Joint Declaration orchestrating the 1997 return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty, China affirmed that after the handover the Special Administrative Region would enjoy for least fifty years a high degree of autonomy, including independent judicial power, including final adjudication. Under the British, Hong Kong residents enjoyed civil liberties, but had only a limited voice in government. In 1990, China's National People's Congress enacted the Basic Law that would guide Hong Kong after 1997. That basic law repeated the pledge of a high degree of autonomy.

One of the ways Hong Kong differed from other places in China was the ability of residents to mobilize and demonstrate to convey their views. This included annual gatherings to remember the violent suppression of the 1989 demonstrations in Beijing and elsewhere, but also massive protests to oppose an anti-sedition bill and other government measures, to seek universal suffrage, and to oppose curriculum reform which promoted moral and national education.

By 2014, large demonstrations had become a primary means of popular expression in Hong Kong. In March of that year, academics and others launched "Occupy Central with Love and Peace" to push for electoral reform. Beijing rejected various reform proposals and the will expressed in an unofficial (and illegal in the eyes of the government) referendum which would permit candidates to be nominated by the public. In August, the central government issued its decision on how the 2017 chief executive selection would be carried out. A nominating committee would submit for popular vote candidates who had been endorsed by more than half of the 1,200 member nominating committee. Both sides, those calling for more direct popular participation and the central government, argued their positions were rooted in Article 45 of the 1990 Basic Law:

"The ultimate aim is the selection of the chief executive by universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly representative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures."

Young protestors, some of them veterans of the 2012 curriculum revision protests, boycotted classes. They were joined by hundreds of thousands of other people in what became known as the Umbrella Movement, drawing on the use protestors made of umbrellas to fend off police pepper spray. The occupation and demonstrations ended in December and several of the leaders were sent to jail.

By 2019, Hong Kong had a new chief executive, long time civil servant Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor. Lam had been selected in the process set out by the central government. Prompted by a murder case involving a Hong Kong man accused of killing his girlfriend during a trip to Taiwan, Lam's administration proposed an extradition bill which, if enacted, would permit the extradition of people from Hong Kong to China (and Macao and Taiwan). Many, including legal and foreign business communities, opposed the proposal which was modified. The revision still garnered opposition and there were massive demonstrations in June and smaller ones through the summer. Protestors adopted new tactics, avoiding formal structures and leaders and moving the protests to different locations. Violence, mostly on the part of the police but including some protestors, became more common. Thousands were arrested and some received jail sentences. Lam eventually withdrew the bill.

The next year, frustrated by the inability of the Hong Kong government to enact such legislation on its own, China's central government enacted a new National Security Law for the Special Administrative Region. Prior to this the U.S. government threatened to remove its special provisions to treat Hong Kong, its companies and its residents differently in legal and commercial affairs from how it treats those from China. After the adoption of the law, U.S. President Donald Trump issued an executive order ending special treatment for Hong Kong entities. Our June 4, 2020 newsletter looked at the measures to reduce Hong Kong's autonomy and how China's economic rise has made the Special Administrative Region less vital to the national economy.

See some of our past events covering dissent in Hong Kong:

Law professor Michael Davis' new book, Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law, looks at Beijing's growing interference in the “one country, two systems” model it promised Hong Kong during the 1997 handover.

Law professor Michael Davis' new book, Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law, looks at Beijing's growing interference in the “one country, two systems” model it promised Hong Kong during the 1997 handover.

Antony Dapiran's book, City on Fire, shows how the 2019 protests fits into the city’s long history of dissent and looks at what the protests will mean for the future of Hong Kong, China, and China’s place in the world.

Antony Dapiran's book, City on Fire, shows how the 2019 protests fits into the city’s long history of dissent and looks at what the protests will mean for the future of Hong Kong, China, and China’s place in the world.

In his book Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, Jeffrey Wasserstrom draws on his long term interest in anti-authoritarian protests to puts events since the 1997 Handover into comparative and historical perspective.

In his book Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, Jeffrey Wasserstrom draws on his long term interest in anti-authoritarian protests to puts events since the 1997 Handover into comparative and historical perspective.

At our 2019 event Hong Kong: What Now? What Next?, panelists in the U.S. and Hong Kong examined the issues driving the protests in Hong Kong, the social composition and motivations of the protesters and counter-protesters, and how the various sides are using media to reach local, mainland and international audiences.

At our 2019 event Hong Kong: What Now? What Next?, panelists in the U.S. and Hong Kong examined the issues driving the protests in Hong Kong, the social composition and motivations of the protesters and counter-protesters, and how the various sides are using media to reach local, mainland and international audiences.

In 2015, David Zweig examined winners and losers in the 2014 protests.

In 2015, David Zweig examined winners and losers in the 2014 protests.