Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

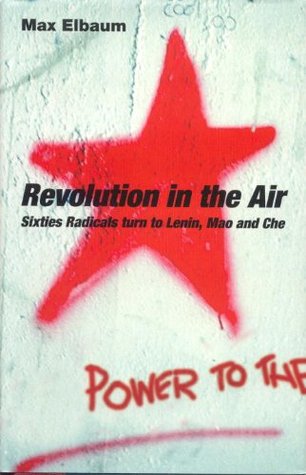

Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che, 2006

For other documents on Mao Zedong, click here.

Reviewed by: Sean Purdy, Departamento de História, Universidade de São Paulo.

Published by: H-1960s (February, 2007)

The affordable paperback edition of Max Elbaum's Revolution in the Air, with a new preface by the author, is a welcome addition  to a burgeoning literature exploring hitherto ignored aspects of the 1960s. Elbaum, an active participant in the events he analyzes, has written an enlightening history of the various groups in the Maoist-influenced New Communist Movement (NCM) from the late 1960s to the 1980s. He joins a growing list of scholars who have made a thoroughly convincing case against the "declension narrative" of ex-leftists like Todd Gitlin, who argue that the legitimate social movements of the early to mid-1960s were eclipsed at the end of the decade by a nihilistic and destructive revolutionary romanticism.[1] Elbaum shows how the "Good Sixties/Bad Sixties" paradigm ignores the deep political crisis of the 1968-73 period and how it shaped the emergence of movements, campaigns, and political organizations, with significant participation by activists of color, who were committed to radical social transformation, antiracism, and anti-imperialism.

to a burgeoning literature exploring hitherto ignored aspects of the 1960s. Elbaum, an active participant in the events he analyzes, has written an enlightening history of the various groups in the Maoist-influenced New Communist Movement (NCM) from the late 1960s to the 1980s. He joins a growing list of scholars who have made a thoroughly convincing case against the "declension narrative" of ex-leftists like Todd Gitlin, who argue that the legitimate social movements of the early to mid-1960s were eclipsed at the end of the decade by a nihilistic and destructive revolutionary romanticism.[1] Elbaum shows how the "Good Sixties/Bad Sixties" paradigm ignores the deep political crisis of the 1968-73 period and how it shaped the emergence of movements, campaigns, and political organizations, with significant participation by activists of color, who were committed to radical social transformation, antiracism, and anti-imperialism.

Generally favorable, the bulk of the reviews of the 2002 hardcover edition focus on Elbaum's persuasive rebuttal of the declension narrative.[2] Some, however, criticize the short shrift he gives to alternative revolutionary currents and his general failure to come to terms with the top-down, anti-democratic theory and practice that underlay the entire Maoist project. I fully agree with these critiques and will touch on some of them. Rather than repeating what has already been said, however, I would like to concentrate, in this brief review, on some of the strengths and weaknesses of Elbaum's historical method and practice.

Revolution in the Air charts the history of various revolutionary communist currents that emerged in the context of the social, cultural, and political ferment of the late 1960s, and later consolidated into more coherent organizations in the 1970s, such as the Revolutionary Communist Party, the Communist Party USA (Marxist-Leninist), Line of March, and the weekly newspaper, The Guardian. These groups were characterized by what Elbaum calls a "Third World Marxism," heavily influenced by (conflicting) understandings of the theoretical and practical experience of communists in Cuba, Africa, Vietnam, and, especially, China. In addition to the necessity to build a revolutionary party of the working class and rigorously follow the theoretical guidance of communist leaders such as Mao Zedong, the NCM "embraced the revolutionary nationalist impulses in communities of color" and "put opposition to racism and military intervention at the heart of its theory and practice" (p. 3). Active on university campuses, as well as in some unions and various social movements, the NCM had some success in recruiting activists of color and influencing local struggles against racial discrimination. Elbaum insightfully describes how the political and social crisis at home and abroad created a context in which revolutionary communist ideas became powerfully attractive to many U.S. activists. Numbering as many as ten thousand members in total, the NCM was able to influence a much wider periphery of activists by the mid-1970s.

Dedicated, courageous, and resourceful, this layer of revolutionary activists would eventually be shattered in the late 1970s by their adherence to the sectarian politics of Maoism and a distortion of Marxism that stressed theoretical purity and ideological discipline. Honestly debating tactics and strategy, recruiting new activists, and building the movement became subordinated to whatever political line was being pitched at the moment by the Chinese or Vietnamese Communist Party or unbending interpretations of such correct political "lines" by revolutionary groups in the United States. Such a stifling political atmosphere repelled potential recruits, impeded solidarity with other activists, and led to wholesale demoralization and resignations among party members. By the late 1980s, many of the NCM organizations had self-destructed.

Ideological rigidity also blinded the NCM cadre from reading the shifting political economic landscape of the period. The global economic crisis that began in 1973, the neoliberal counter-offensive launched by the ruling class, and declining confidence among workers regarding the possibilities for social transformation signified a downturn in both workers' and social movements by the late 1970s.[3] NCM groups, reared in a climate of optimistic political voluntarism, were unable to adjust to the new political and economic realities. Despite all these problems, Elbaum contends that the NCM left a positive legacy of internationalism, anti-imperialism, antiracism, and serious cadre-building practices for the activists of today.

However problematic their politics, it is significant that Elbaum takes these revolutionary groups seriously and as worthy of study. Drawing on an impressive range of secondary sources and NCM literature, his study sheds light on the continuities and discontinuities of the Old and New Left; the influence of transnational ideas and movements; the profound social and political crisis of the period and its impact on young people; and the theoretical formation and organizational practices of the left and social movements. It is not entirely clear where Elbaum now draws the line between revolutionary politics and reformism (he praises NCM involvement in the Rainbow Coalition and suggests that activists should consider future collaboration with the Democratic Party). On the whole, however, today's activists have much to learn from the candid evaluation of the successes and weaknesses of the NCM that Elbaum offers in Revolution in the Air.

Elbaum is a fine writer whose analysis is generally dispassionate and lucid. I was particularly impressed in chapter 1, as well as the introductory passages to other chapters, where he lays out concise political and economic contexts for the particular issues and time periods discussed, something that is frequently missing in topical monographs. Indeed, these passages could serve as succinct reading assignments to provide students with the larger contexts that shaped the formation of social movements in the 1960s and 1970s.

Given that this is the first comprehensive history of such revolutionary groups, it is understandable that Elbaum utilizes the most accessible and conventional primary sources such as formal party documents as well as his own personal recollections. His decision to withhold the names of many of the ex-leaders and rank-and-file activists of the NCM, to protect their privacy, is understandable, but it sometimes leaves his analysis dry and without sufficient explanatory details. Given Elbaum's frank admission that the NCM made no lasting contributions to Marxist theory, there are overly exhaustive discussions of the theoretical debates of the various groups about the nature of the American working class, racism, and international Maoism, among other topics. He provides the general theoretical orientation and political approaches of the NCM groups to particular issues such as the Boston busing crisis, but there is little analysis of their activities on the ground. What were their organizational routines and fundraising practices? What were their recruitment mechanisms? How did they relate to and work with non-party movement activists and leaders? We get the overall theoretical bones of the movement, but little of the day-to-day flesh of political practice. Elbaum neglects to discuss or utilize agitational material such as party newspapers, leaflets, banners, and placards, or describe demonstrations, strike support work, and other public actions. A few detailed case studies of NCM campaigns utilizing a more diverse range of sources, such as non-party literature and interviews, would have enriched the analysis and given the reader more of a "feel" for the movement--as historians of the Communist Party in the 1930s and 1940s have accomplished.[4]

Despite these criticisms, Revolution in the Air offers useful insights for scholars into the political economic context of the period, the vigor and commitment of NCM cadre, their attempt to bridge racial divisions in the working class, and the reason why significant layers of activists were pulled towards "Third World Marxism" and the necessity to build a revolutionary party. It also serves as a valuable primer for activists in the thick of the fire this time.

Notes

[1]. Elbaum usefully notes in his preface (dated April 2006) that many reviews of the hardcover edition are collected at www.revolutionintheair.com.

[2]. For a stimulating review of the literature, see Van Gosse, "A Movement of Movements: The Definition and Periodization of the New Left," in A Companion to Post-1945 America, ed. Jean-Cristophe Agnew and Roy Rozenzweig. (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), 277-302. For a fine recent study in the same spirit as Elbaum's, see Rhonda Y. Williams, The Politics of Public Housing: Black Women's Struggles against Inequality (New York and London: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[3]. This is the argument made by Chris Harman in one of the first and best global histories of the 1960s, a study surprisingly underutilized by U.S. scholars. Chris Harman, The Fire Last Time: 1968 and After (London: Bookmarks, 1998).

[4]. For example note, Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990); and Mark Naison. Communists in Harlem during the Depression (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983). But note Bryan D. Palmer's useful critique in "Rethinking the Historiography of American Communism," American Communist History 2, no.2 (Winter 2003), 139-173.

Republished with permission from H-Net Reviews.

Other documents on Mao Zedong:

Sixties Radicals turn to Lenin, Mao and Che | Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War | Mao Zedong meets Richard Nixon | Foreword to the Second Edition of The Quotations of Chairman Mao | China Will Take a Giant Stride Forward | Order to the Chinese People's Volunteers | Conversation between the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin and China's Mao Zedong | The Chinese People Have Stood Up!

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.