Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

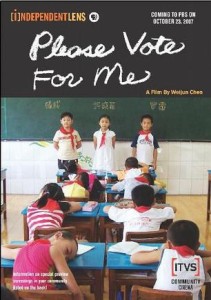

Chen Weijun, Please Vote for Me (film), 2007

Directed by Chen Weijun. 2007. 55 minutes. In Chinese with English subtitles.

Reviewed by: Clayton Dube, US-China Institute, University of Southern California, USA.

An abridged version of this review was published by Asian Educational Media Service (Fall, 2008)

What is democracy? Please Vote for Me opens with the unseen filmmaker asking this of a third grade student in Wuhan, China. This student and his classmates are about to embark on an experiment: the election of their class monitor. As Teacher Zhang  makes clear at the outset, this is a contrived situation. The norm is for teachers (at all levels, including college) to appoint class monitors who assist them in maintaining discipline and enforcing the rules. For this exercise, teachers at Changping No. 1 Elementary School have selected three students that the students may choose among. The one hour documentary follows the two-week campaign from the introduction of the candidates to the final voting. Students at all levels will gain from watching this reality-show style film.

makes clear at the outset, this is a contrived situation. The norm is for teachers (at all levels, including college) to appoint class monitors who assist them in maintaining discipline and enforcing the rules. For this exercise, teachers at Changping No. 1 Elementary School have selected three students that the students may choose among. The one hour documentary follows the two-week campaign from the introduction of the candidates to the final voting. Students at all levels will gain from watching this reality-show style film.

Most of their classmates already know the three candidates well, but viewers will as well by the end of the film. Luo Lei is the son of two police officers and has already been a class monitor for two years. We see him enforcing nap time standards and get some sense of his stern leadership style. Cheng Cheng, one of his opponents, will use his tendency to strike others as a major reason why he shouldn’t continue as monitor. Cheng Cheng is a gregarious fellow whose mother is a television producer and whose stepfather is an engineer. He’s a master politician, shaking hands, getting others to sling mud, and even managing to point fingers at Luo Lei when Teacher Zhang steps in to criticize the class for intimidating and shouting down Xu Xiaofei, the third candidate. Xiaofei is the daughter of a school administrator, a single mom who suffers along with her daughter when she breaks into tears. Xiaofei is a quick student, though, and before long is preparing for expected negative attacks, leading research into her opponent’s shortcomings, and joining in shouting at the poor singing of one of her opponents.

And one’s singing ability matters. The campaign includes a talent demonstration. Why this is the case is hardly clear, but it certainly fits with the passion the Chinese public has for such things. The biggest election ever held in China was for the 2004-2006 televised “SuperGirl” singing competitions. As in many elections elsewhere, promises and personality count for a great deal at Changping No. 1. Luo Lei and Xu Xiaofei play the flute and Luo Lei and Cheng Cheng sing. Each has two assistants who provide moral support, rally supporters, and, in this instance dance or clap to support their candidate.

Early in the contest, Cheng Cheng’s verbal dexterity and detailed debate preparation place him well in front of his rivals. At this point, however, Luo Lei’s father, who is a high-ranking police official, helps the boy turn the tide. Early in the electoral process, Luo Lei insisted he didn’t want his parents to help him, in fact, he said then that he didn’t want to dragoon others into supporting him. After a bout of depression and muttering that he wanted to drop out of the campaign, Luo Lei is now quite willing to accept his father’s help. The police official arranged for the class to get a free field trip to ride on Wuhan’s monorail. The Wuhan monorail opened in 2004 and is impressive. The children love the views and Luo Lei is happy to take credit for making the adventure possible. No polls are taken, but Cheng Cheng is clearly worried that Luo Lei’s ability to deliver to his constituency has put him out in front. In the final round of candidate speeches, Luo Lei shows that he’s sensitive to complaints about his tendency to hit his classmates and explains that he has and will continue to change. And then he wishes his classmates a great Mid-Autumn Festival and presents each of them with holiday cards purchased by his parents. He ends up winning by a landslide.

This film could be usefully employed by teachers from upper elementary grades through undergraduate courses. In addition to sparking a great deal of discussion of potential advantages and disadvantages of democratic selection of leaders and of what the course of this election reveals about democracy or Chinese children, it also affords opportunities to discuss many other important issues. One of these is the impact of China’s family planning regulations. Nearly all of the children in the class are only children and most have at least six adults (two parents and four grandparents) who lavish attention and goods on them. After the May 12, 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, many grieving parents said that their futures died with their children. It’s clear from this documentary that parents have a lot invested in their children. The documentary also provides glimpses into class divisions (the police official owns an automobile), everyday family life (homework, play, and eating), and school routines (flag raising, dining, eye exercises, and calisthenics).

How “real” is this compelling story? In an interview with tjbkids, a website for Beijing expatriate families, the filmmaker Chen Weijun is quick to insist that he did not structure the activities or suggest strategies to parents or children. He did ask teachers to ensure that the election be fair and the vote be counted publicly. It’s important to note, though, that the entire election came about because Chen had been commissioned by STEPS International, a South African production company, to make a film for its Why Democracy? series. Chen knew Cheng Cheng’s mother and was much intrigued by the boy who told him he hoped to be a political figure like China’s president Hu Jintao. According to producer Don Edkins of STEPS International, school authorities were reluctant to go along with the experiment, but the parents of the three candidates welcomed the filmmaker into their homes and allowed the children to wear wireless microphones. The film has been broadcast by PBS in its Independent Lens series (whose website includes considerable background information) and has been screened in many other countries, though not in China.

The film and its supporting websites slightly exaggerate the uniqueness of this effort. For twenty years, hundreds of millions of Chinese villagers have been electing village leaders. Those elections are not uniformly open and contested. In many cases, local Party leaders or township officials decide who can be a candidate, much like the pre-screening that teachers conducted at Changping No. 1. Village elections are primarily designed to help defuse tensions between state and society by permitting rural residents to choose among themselves who should represent the community. Nonetheless, Please Vote for Me is a fascinating look at how children, parents, and teachers in a huge and modernizing Chinese city understand democracy, authority, and power.

This is Chen Weijun’s second documentary to receive international attention. He is an independent filmmaker whose day job has been producing Party-State pleasing stories for Wuhan television. His 2003 film, To Live is Better Than to Die, on how AIDS ravaged a village in Henan province won a number of awards. Though it’s not mentioned in the film or on any of its supporting websites, it may be significant that Chen was a first year journalism student in Chengdu at Sichuan University in 1989 when pro-democracy protests broke out in Beijing, Chengdu, and many other Chinese cities. Please Vote for Me suggests that Chinese children, like those elsewhere, have an innate sense of fairness and that democracy can be messy. Though incumbency and resources make the difference in this election, Please Vote for Me, also demonstrates that the process itself requires candidates to be responsive to popular concerns. Will Luo Lei be a less dictatorial monitor? The film doesn’t show us. And if the electoral experiment isn’t repeated, isn’t made part of the routine, what incentive has he to really change?

HOW TO PURCHASE: Please Vote For Me is available on DVD from First Run Features: $195 for educational institutions and $24.95 for consumers. It is also available at Amazon.com.

Additional Resources

The Why Democracy? Project website offers a trailer and background information on the film, the director, and contemporary China: www.whydemocracy.net/film/3.

PBS’s Independent Lens also hosts a website on the film, with background information and comments from viewers: www.pbs.org/independentlens/pleasevoteforme.

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.