Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

U.S. Trade Representative, Chinese Technology Transfer Policies and Practices, March 22, 2018

The U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer issued this report on its investigation in 2018, one month before the start of a U.S.-China trade war.

The full text report is available as a pdf download at the link below. Some excerpts:

Background to the investigation (p. 4)

On August 14, 2017, the President issued a Memorandum to the Trade Representative stating inter alia that:

China has implemented laws, policies, and practices and has taken actions related to intellectual property, innovation, and technology that may encourage or require the transfer of American technology and intellectual property to enterprises in China or that may otherwise negatively affect American economic interests. These laws, policies, practices, and actions may inhibit United States exports, deprive United States citizens of fair remuneration for their innovations, divert American jobs to workers in China, contribute to our trade deficit with China, and otherwise undermine American manufacturing, services, and innovation.

The President instructed USTR to determineunder Section301whether to investigate China’s law, policies, practices,or actions that may be unreasonable or discriminatory and that may be harming American intellectual property rights, innovation, or technology development.11Concerns about a wide range of unfair practices of the Chinese government(and the Chinese CommunistParty (CCP)) related to technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation are longstanding. USTR has pursued these issues multilaterally, for example, through the WTO dispute settlement process and in WTO committees,and bilaterally through the annual Special 301 review. These issues also have been raised in bilateral dialogueswith China, including the U.S.-China Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade (JCCT) and U.S.-China Strategic & Economic Dialogue (S&ED), to attempt to address some of the U.S. concerns.

China’s Bilateral Commitments to End its Technology Transfer Regime and to Refrain from State-Sponsored Cyber Intrusions and Theft (p. 6)

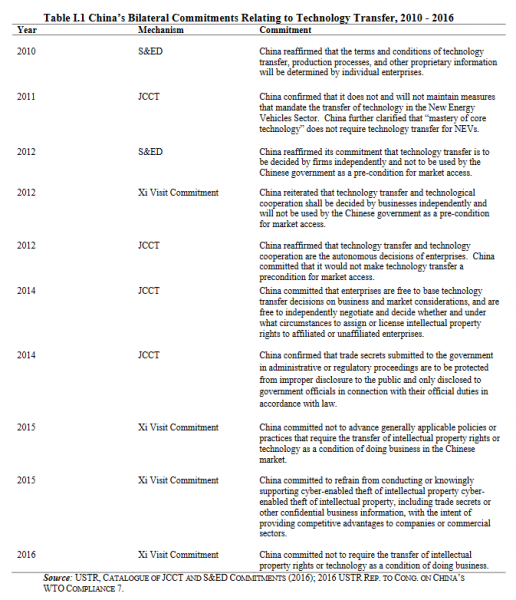

In the bilateral relationship, China repeatedly has committed to eliminate aspects of its technology transfer regime. On at least eight occasionssince 2010, the Chinese government has committed not to use technology transfer as a condition for market access and to permit technology transfer decisions to be negotiated independently by businesses. China has further committednot to pressure the disclosure of trade secrets in regulatory or administrative proceedings. The evidence adduced in this investigation establishes that China’s technology transfer regime continues, notwithstanding repeated bilateral commitments and government statements, as summarized in Table I.1, below, and discussed in the remainder of this report.

China's techonology drive (p. 10)

Official publications of the Chinese government and the CCP set out China’s ambitious technology-related industrial policies. These policies are driven in large part by China’s goals of dominating its domestic market and becoming a global leader in a wide range of technologies, especially advanced technologies. The industrial policies reflect a top-down, state-directed approach to technology development and are founded on concepts such as “indigenous innovation” and “re-innovation” of foreign technologies, among others. The Chinese government regards technology development as integral to its economic development and seeks to attain domestic dominance and global leadership in a wide range of technologies for economic and national security reasons.24China accordingly seeks to reduce its dependence on technologies from other countries and move up the value chain, advancing from low-cost manufacturing to become a “global innovation power in science and technology.”25In pursuit of this overarching objective, China has issued a large number of industrial policies, including more than 100 five-year plans, science and technology development plans, and sectoral plans over the last decade.26Some of the most prominent industrial policies include the National Medium-and Long-Term Science and Technology Development Plan Outline (2006-2020)(MLP),27theState Council Decision on Accelerating and Cultivating the Development of Strategic Emerging Industries(SEI Decision),and, more recently, the Notice on Issuing “Made in China 2025”(Made in China 2025 Notice).

The MLP issued in 2005 and covering the period 2006 to 2020, is the seminal document articulating China’s long-term technology development strategy. The MLP recognizes the country’s “relatively weak indigenous innovation capacity,” its “weak core competitiveness of enterprises,” and the fact that the country’s high-technology industries “lag” those of more developed nations.”

Official publications of the Chinese government and the CCP set out China’s ambitious technology-related industrial policies. These policies are driven in large part by China’s goals of dominating its domestic market and becoming a global leader in a wide range of technologies, especially advanced technologies. The industrial policies reflect a top-down, state-directed approach to technology development and are founded on concepts such as “indigenous innovation” and “re-innovation” of foreign technologies, among others. The Chinese government regards technology development as integral to its economic development and seeks to attain domestic dominance and global leadership in a wide range of technologies for economic and national security reasons.24China accordingly seeks to reduce its dependence on technologies from other countries and move up the value chain, advancing from low-cost manufacturing to become a “global innovation power in science and technology.”25In pursuit of this overarching objective, China has issued a large number of industrial policies, including more than 100 five-year plans, science and technology development plans, and sectoral plans over the last decade.26Some of the most prominent industrial policies include the National Medium-and Long-Term Science and Technology Development Plan Outline (2006-2020)(MLP),27theState Council Decision on Accelerating and Cultivating the Development of Strategic Emerging Industries(SEI Decision),and, more recently, the Notice on Issuing “Made in China 2025”(Made in China 2025 Notice). The MLP issued in 2005 and covering the period 2006 to 2020, is the seminal document articulating China’s long-term technology development strategy. The MLP recognizes the country’s “relatively weak indigenous innovation capacity,” its “weak core competitiveness of enterprises,” and the fact that the country’s high-technology industries “lag” those of more developed nations.”

As its focus, the MLP identifies 11 key sectors, and 68 priority areas within these sectors, for technology development.31It also designates eight fields of “frontier technology,”32within which27 “breakthrough technologies” will be pursued, and highlights four major scientific research programs.33The MLP also establishes the cross-cutting goal of reducing the rate of dependence on foreign technologies in the identified sectors to below 30%by the year 2020.34The MLP strategy for securing sought-after technology development includes several key elements, which continue to have a negative impact on U.S. and other foreign companies:

·A top-down national strategy, in which implementation requires the mobilization and participation of all sectors of society35and the integration of civil and military resources;

·Prioritization of certain industries and technologies for development,37particularly those that can advance“ sustainable development,” “core competitiveness,” “public service,” and “national security” objectives.

·Leveraging state resources and regulatory systems;

·Import substitution to be achieved through “indigenous innovation”40and re-innovation based on assimilation and absorption of foreign technologies; and

·Promoting Chinese enterprises to become dominant in the domestic market42and internationally competitive enterprises43in key industries.

The MLP set in motion a web of policies and practices intended to drive innovation and re-innovation. For example, Section 8(2) of the MLP calls for “enhancing the absorption, digestion, and re-innovation of introduced technology.” Following the issuance of the MLP, China detailed these policies in the Several Supporting Policies for Implementing the “National Medium-and Long-Term Science and Technology Development Plan Outline (2006-2020)” (MLP Supporting Policies) and the Opinions on Encouraging Technology Introduction and Innovation and Promoting the Transformation of the Growth Mode in Foreign Trade(IDAR Opinions),which articulate the concept of Introducing, Digesting, Absorbing, and Re-innovating foreign intellectual property and technology (IDAR). The IDAR approach involves four steps, each of which hinges on close collaboration between the Chinese government and Chinese industry to take full advantage of foreign technologies:

Introduce:

Chinese companies should target and acquire foreign technology. Methods of “introducing” foreign technology that are specifically referenced include: technology transfer agreements, inbound investment, technology imports, establishing foreign R&D centers, outbound investment, and the collection of market intelligence by state entities for the benefit of Chinese companies. Technology to be “introduced” from overseas includes “major equipment that cannot yet be supplied domestically”, as well as “advanced design and manufacturing technology”; conversely, the government discourages imports of technologies for which China is already deemed to “possess domestic R&D capabilities.”

Digest:

Following the acquisition of foreign technology, the Chinese government should collaborate with China’s domestic industry to collect, analyze, and disseminate the information and technology that has been acquired.

Absorb:

The Chinese government and China’s domestic industry should collaborate to develop products using the technology that has been acquired. The Chinese government should provide financial assistance to develop products using technology obtained through IDAR, including foreign trade development funds, government procurement, and fiscal incentives. To absorb foreign technologies, authorities have established engineering research centers, enterprise-based technology centers, state laboratories, national technology transfer centers, and high-technology service centers.

…

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.