Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

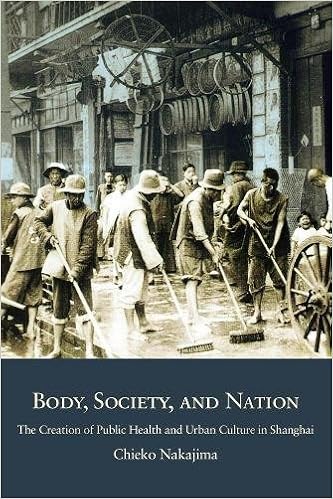

Nakajima, Body, Society, and Nation: The Creation of Public Health and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 2018.

Chieko Nakajima's book was reviewed by John Knight for the History of Socialisms discussion list. It is reprinted here by Creative Commons license.

Chieko Nakajima. Body, Society, and Nation: The Creation of Public Health and Urban Culture in Shanghai. Cambridge Harvard University Asia Center, 2018.

Public Health in Shanghai

Western medicine and modern hygiene practices entered China by way of imperialist assault. In 1861, following China's defeat in the Second Opium War (1856-60), the British-run Shanghai Municipal Council appointed the city's first health inspector so as to safeguard foreign residents from the "dirty" environment and "unsanitary natives" (p. 86). Chinese conceptions of "good health" gradually aligned with Western standards over the following decades, with native political and business leaders in the Republican era (1911-49) calling for the adoption of Western medical and hygiene practices as a way to demonstrate national and racial strength. Given the unequal balance of power in this exchange, it would be tempting to argue that China's traditional medical knowledge was negated by a colonizing force. Cheiko Nakajima, an independent scholar in the fields of Chinese and medical history, challenges such a rigid view. Her first monograph, _Body, Society, and Nation: The Creation of Public Health and Urban Culture in Shanghai_, asserts that even during the Republican period, Chinese and Western medical practices were mutually influential. Rather than being the passive victims of colonial aggression, Shanghai's Chinese residents maintained their creative agency, and "colonial medicine and hygienic modernity could become part of local culture without undermining Chinese identities or destroying local businesses" (p. 21). Nakajima bases her argument on institutional records gathered from the Shanghai Municipal Archives and the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan as well as medical journals, newspapers, and popular magazines from the era. Although at times a bit dry, there is no doubt that _Body, Society, and Nation_ helps to uncover "the complexity and plurality of China's unfolding modernity" (p. 1).

Western medicine and modern hygiene practices entered China by way of imperialist assault. In 1861, following China's defeat in the Second Opium War (1856-60), the British-run Shanghai Municipal Council appointed the city's first health inspector so as to safeguard foreign residents from the "dirty" environment and "unsanitary natives" (p. 86). Chinese conceptions of "good health" gradually aligned with Western standards over the following decades, with native political and business leaders in the Republican era (1911-49) calling for the adoption of Western medical and hygiene practices as a way to demonstrate national and racial strength. Given the unequal balance of power in this exchange, it would be tempting to argue that China's traditional medical knowledge was negated by a colonizing force. Cheiko Nakajima, an independent scholar in the fields of Chinese and medical history, challenges such a rigid view. Her first monograph, _Body, Society, and Nation: The Creation of Public Health and Urban Culture in Shanghai_, asserts that even during the Republican period, Chinese and Western medical practices were mutually influential. Rather than being the passive victims of colonial aggression, Shanghai's Chinese residents maintained their creative agency, and "colonial medicine and hygienic modernity could become part of local culture without undermining Chinese identities or destroying local businesses" (p. 21). Nakajima bases her argument on institutional records gathered from the Shanghai Municipal Archives and the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan as well as medical journals, newspapers, and popular magazines from the era. Although at times a bit dry, there is no doubt that _Body, Society, and Nation_ helps to uncover "the complexity and plurality of China's unfolding modernity" (p. 1).

Chapter 1 examines Shanghai's early hospitals, finding parallels between these "modern" institutions and traditional approaches to public health care. Renji Hospital, still very successful today, was founded by the London Missionary Society in 1844. Renji began as a philanthropic institution, providing free medical care and religious teaching to Shanghai's poorer inhabitants. Tongren Hospital, opened in 1866 by the Episcopal Church, likewise started as a charitable clinic. Nakajima sees overlap between these early missionary hospitals and benevolent halls (_shantang_), which, beginning in the late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), provided free medical care, clothing, and coffins to those in need. Perhaps it is because of this similarity that neither Renji nor Tongren were ever the target of antiforeign demonstrations, even in an era of rising nationalist sentiment. It is also important to keep in mind that Western medical techniques in the mid-nineteenth century were not necessary superior to those of China. However, by century's end, European science had made important breakthroughs in the fields of anesthesiology, radiology, and elsewhere. Renji and Tongren rebranded themselves as centers for "advanced research" with "state-of-the-art" technology, and began charging their patients in the process. Stepping in to fill the charitable void was the Chinese Infectious Disease Hospital (CIDH), a Chinese-run institution that included Du Yuesheng (1888-1951) and Huang Jinrong (1868-1953), members of Shanghai's nefarious Green Gang, among its donors. Like the benevolent halls, CIDH enjoyed elite backing and was open to all, regardless of age, residency, or economic status. By the early 1930s, CIDH had grown to be the city's preeminent cholera treatment center, handling nearly half of all cases. Chinese hospitals did not supplant traditional healthcare facilities, but built upon their strengths.

Chapter 2 covers the expanding role of government in public health during both the Republican and Japanese-occupied regimes, arguing that "good health" was a universal goal able to transcend national identities at the same time that it paradoxically brought the people within each nation under tighter government control. In April 1927, soon after securing power in a violent coup, Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975) opened the Shanghai Municipal Public Health Bureau (PHB) with the goal of making the Chinese-run section of the city comparable with that of the foreign settlements. Chiang and other Guomindang (GMD) leaders believed "a messy and polluted city would justify the presence of imperialists in China;[therefore] sanitation, cleanliness, and orderliness were prerequisite for a modern city and a key to successful recovery of foreign concessions" (p. 77). In its efforts to "sanitize" the city, the PHB "not only provided necessary services but also began to control people's behavior and intrude into their personal lives" (p. 23). Mandatory injection booths became a common sight on city streets, and the PHB sent injection teams to schools, factories, and prisons to combat cholera and smallpox. These highly visible campaigns "provided an opportunity for Chinese administrators to demonstrate their administrative capability to foreigners" (p. 108). Further, injection booths, "with their syringes, cotton balls, vaccines, and doctors and nurses in white coats embodied modern biomedicine and administrative authority" (p. 108). Such preventive measures continued during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), but, following the occupation of Shanghai, did so under foreign supervision. Although two Chinese commissioners of public health were imprisoned afterwards for treason, Nakajima does not think that Shanghai healthcare professionals saw their wartime work as collaborating with the enemy. Instead, "faith in biomedicine and the threat of an epidemic united the Chinese and Japanese" (p. 127). Such biomedical faith also expanded the reach of the government, making once-private bodies and behaviors public.

The focus of chapter 3 is on government-run hygiene campaigns (_weisheng yundong_) during the Republican era. These campaigns, which lasted from one to ten days, "confirmed that making a hygienic city was a responsibility that belonged to all Shanghai residents, regardless of social class" (p. 24). Nakajima finds precedence for these campaigns in the Confucian belief in "the perfectibility and educability of humans" (p. 130). In fact, before Shanghai's PHB held its first hygiene campaign in April 1928, similar drives were already being run by the city's YMCA, often timed to coincide with traditional holidays such as the Dragon Boat Festival. What distinguished government-run hygiene campaigns from these earlier ventures was their nationalist emphasis. The GMD employed hygiene campaigns not only to promote health, but "to transform the Shanghai populace into informed citizens, who would be a cornerstone of a modern city and a strong nation" (p. 130). The national and racial implications of health became especially clear during the New Life Movement, a government-sponsored mass movement launched in 1934 that combined Confucianism with patriotism alongside injunctions on cleanliness and orderliness. Subsequent hygiene campaigns were less concerned about the promotion of medical knowledge than "instruction on maintaining a correct personal mentality and spirit" (p. 144-45). By linking public health and personal habits with loyalty to the nation and the GMD, Republican-era hygiene campaigns inadvertently guaranteed the future public acceptance of similar campaigns launched by the Chinese Communist Party.

Chapter 4 investigates the marketing strategies of entrepreneurs, specifically those of Fang Yexian (1893-1940) and Chen Diexian (1879-1940), who realized that "good health" could add value to their wares. Nakajima deems manufacturers to be "even more successful than the state in localizing and popularizing hygiene modernity among Shanghai residents through their advertising and sales" (p. 25). Fang's Chemical Industries Company was the largest producer of toiletries and personal hygiene products in Republican China, and Chen's Household Industries Company was not far behind. Both companies "encouraged consumers to practice hygiene as prescribed by the state and to purchase their commodities as a means to do so" (p.

25). They also took on prominent roles in the National Products Movement, even though many of Fang's goods "were imitations of foreign brands and their ingredients and recipes were based on those of foreign companies" (p. 207). Although business ventures, like public health, assumed nationalist overtones during the Republican era, Nakajima believes that "the main interest of Shanghai's entrepreneurs still lay in sales of their commodities--not in supporting national salvation or spreading medical knowledge" (p. 224). However, considering that Fang was killed in 1940 for refusing to collaborate with Shanghai's Japanese occupiers, I wonder if Nakajima's assertion of a self-interested entrepreneurial spirit is accurate. Perhaps business leaders, like Shanghai's common citizens, also internalized a discourse that linked entrepreneurship, patriotism, and public health.

The conclusion examines the evolving status of healthcare in the People's Republic (1949-). Communist China's first hygiene campaign took place in 1952, in response to America's alleged use of germ warfare in the Korean peninsula. Leaving the veracity of such claims aside, "the campaigns provided an opportunity for the new state to penetrate into the local community and demanded personal dedication through workplace and neighborhood networks" (p. 243). Following the script laid down by the GMD in the 1930s, the Chinese Communist Party employed public health to secure the loyalty of the individual to the party and nation. Unlike the Republican period, however, there was no room for private hospitals or entrepreneurs in the early Communist regime. All hospitals were placed under government jurisdiction and businesses were nationalized. While the agency of healthcare officials and entrepreneurs was circumscribed, more Chinese got to experience "modern" healthcare than ever before. Nakajima considers that "lane hospitals, which had direct contact with local residents, best represent the socialist ideal of community health" (p. 234). Lane hospitals (_jiedao yiyuan_) were small clinics that offered both Chinese and Western medical treatment to outpatients and played a leading role in implementing government health campaigns. China's state-run medical system has markedly deteriorated since the advent of market reforms in the 1980s, and while the amount of services has increased, overall coverage has not. Yet, even in the contemporary era, rhetorical ties between body, society, and nation remain. For example, "the accusation that China's 'backward' practices contributed to the outbreak and spread of SARS caused 'global embarrassment' and threatened China's status as a modern state" (p. 245).

Finally, to make her study more approachable for a wider audience, the author includes an appendix explaining Republican Shanghai's system of foreign concessions, which divided the city into Chinese, French, and International zones, as well as a translation of a lecture outline for the 1942 summer public health campaign carried out under Japanese occupation. While I found Nakajima's account fascinating on the whole, there were times when I wondered if the author's institutional focus could have benefited from a more discursive approach. A fifth chapter tracing the development of popular and intellectual conceptions of public health in the Republican mediasphere, for example, would have helped to personalize the cultural, political, and technological changes Nakajima describes. I also would have liked more information on the private lives and motivations of Chen Diexian and Fang Yexian. Slight reservations aside, _Body, Society, and Nation_ is an important and meticulously researched work. It will interest scholars in East Asian studies as well as those working in urban studies, medical history, and multiple modernities more broadly.

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.