Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

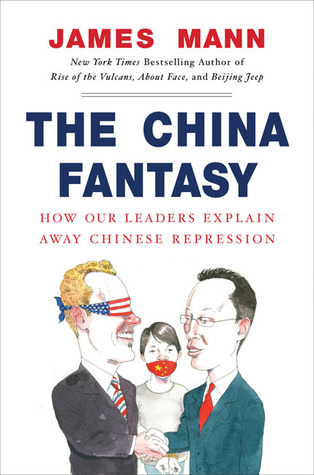

Mann, The China Fantasy: How Our Leaders Explain Away Chinese Repression, 2007

This review was originally published by AsiaMedia on March 6, 2007. Republished by permission

The China Fantasy: How Our Leaders Explain Away Chinese Repression

James Mann

144 pages: Viking Adult: 2007. US$19.95.

Former Los Angeles Times Beijing bureau chief James Mann's new book, The China Fantasy, is getting lots of attention. This suggests that Americans are eager, as we should be, to move beyond the fantasy-skewed vision of the People's Republic of China that has long clouded our understanding of the world's most populous country.

Former Los Angeles Times Beijing bureau chief James Mann's new book, The China Fantasy, is getting lots of attention. This suggests that Americans are eager, as we should be, to move beyond the fantasy-skewed vision of the People's Republic of China that has long clouded our understanding of the world's most populous country.

Too bad that Mann's book is such a flawed effort to move us in that worthy direction.

One problem is his overstating the novelty of his own view of China as a country that, politically, hasn't changed much lately and is unlikely to change anytime soon. This stand, he insists, contradicts the established wisdom as articulated by "academic China hands," recent Democratic and Republican administrations, and prominent journalists.

According to Mann, most influential U.S. commentators on China have fallen under the spell of the "Soothing Scenario." They assume that China will become a liberal democracy once the market and the Web have time to work their magic. The only alternative view that gets any attention, he asserts, is the "Upheaval Scenario," which sees China nearing a destabilizing, perhaps catastrophic breakdown. Mann complains that both scenarios involve inaccurate predictions. He endorses a "Third Scenario" that posits the PRC simply remaining authoritarian.

He criticizes the established wisdom for a China policy that is too soft on human rights. Optimists want to reward Beijing for moving in the right direction, while pessimists suggest Beijing be treated gingerly, since at least it is a devil we know.

Mann effectively skewers the wishful thinking on which the Soothing Scenario depends and the tendency of proponents of the Upheaval Scenario to be overly alarmist. I admire his dismissal of "China Threat" hysterics even as he calls for a harder line. He wants more attention paid to human rights not out of paranoia, but simply because no regime's abuses should be overlooked.

But Mann goes badly astray on two fronts.

First, he insists that his "Unchanging Authoritarianism Scenario" (my term) is not already part of the debate. It got plenty of attention before his book came along. Second, he gives the impression that China can only be seen as Americanizing, imploding, or changeless. There are other options.

One specific incorrect claim of Mann's is revealing: He says that there is a consensus among influential voices on China that 1989's June 4th Massacre be dismissed as an irrelevant bit of history. In fact, prominent China specialists often continue to stress the significance of Tiananmen.

Take Andrew Nathan, an endowed professor at Columbia University who writes on China in influential venues such as Foreign Affairs, the New Republic and the New York Review of Books. He embraces neither the Soothing Scenario nor the Upheaval Scenario in his writings. And his introduction to The Tiananmen Papers -- a much-discussed 2002 publication that was published in part precisely to stress the ongoing relevance of the June 4th Massacre -- put forward a version of the Unchanging Authoritarianism Scenario. So much for Mann being a lone voice in the wilderness.

It is no surprise that China Fantasy comes endorsed by Nathan. What would be surprising would be considering Nathan so marginal a figure that his views are not part of the established wisdom.

More significantly, there are many China specialists, myself included, who do not embrace any of the three scenarios Mann mentions. Members of this loosely defined group, which includes academics and journalists alike, feel that the PRC has been changing a great deal, and not just economically. We stress in our writings that China still does not hold free elections, but neither is it the same kind of authoritarian state it once was. We do not ignore popular discontent, censorship, and human rights abuses. In fact, some of us write a lot about these issues -- and while doing so do not sugarcoat the regime's behavior.

But we think it important to try to understand better the myriad, often confusing transformations that have made today's China dissimilar from that of Mao Zedong's or even Deng Xiaoping's days. And because visions of China as unchanging as opposed to a much-altered authoritarian state often seem to fit too neatly into old Cold War categories, we also sometimes stress things that make the 21st century PRC dissimilar from former Soviet bloc countries. One telling shift I like to note is that Soviet bloc scholars with American doctorates almost never returned to teach in their homelands, but now some Chinese do.

We lament the persistence of old problems (such as official corruption) and the appearance of new ones (including forms of inequality linked to privatization that particularly disadvantage women). But we are heartened by the state's long-term shift away from micromanaging private lives and from punishing people simply for what their friends or relatives said or did.

The biggest problem with The China Fantasy may be the title's final word. Mann should have made it plural. The Americanization myth should be retired. But so should the fairy tale that China is a land strangely impervious to change. There's more than one China fantasy we need to put behind us.

*****************************************************************

The Los Angeles Times’s former Beijing bureau chief argues U.S. leaders promised that engagement with China would lead that nation to undergo significant political change. He argues China’s likely to continue under an authoritarian regime. Jeffrey Wasserstrom challenges this and the author’s neglect of the range of views regularly expressed by American China specialists. Prof. Wasserstrom has also edited other books, contributed commentaries to periodicals such as the Los Angeles Times and the Nation, and served as a consultant for influential documentaries on the 1989 Tiananmen protests and the Cultural Revolution.

Featured Articles

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

Events

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?