Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

John Demers, China’s Non-Traditional Espionage Against the United States, December 12, 2018

A statement by the Assistant Attorney General of the National Security Division before the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate.

Statement of John C. Demers

Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division

U.S. Department of Justice

Before the Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

December 12, 2018

China’s Non-Traditional Espionage Against the United States: The Threat and Potential Policy Responses

December 12, 2018

Good morning Chairman Grassley, Ranking Member Feinstein, and distinguished Members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to testify on behalf of the Department of Justice (Department) concerning China’s economic aggression, its efforts to threaten our national security on several, non-traditional fronts, and our efforts to combat them. The Department views this threat as a priority, and last month the former Attorney General announced an initiative to marshal our resources to better address it. This initiative continues, and I am privileged to lead this effort on behalf of the Department. I especially appreciate the Committee’s interest in this area of growing concern.

I will begin by framing China’s strategic goals, including its stated goal of achieving superiority in certain industries, which, not coincidentally, corresponds to thefts of technology from U.S. companies in those industries. I will then describe some of the unacceptable methods by which China is pursuing (or could pursue) those goals at our expense. Finally, I will explain what the Department is doing about it, including through our China Initiative.

I. China’s Strategic Goals

Official publications of the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party set out China’s ambitious technology-related industrial policies. These policies are driven in large part by China’s goals of dominating its domestic market and becoming a global leader in a wide range of technologies, especially advanced technologies. The industrial policies reflect a topdown, state-directed approach to technology development and are founded on concepts such as “indigenous innovation” and “re-innovation” of foreign technologies, among others. The Chinese government regards technology development as integral to its economic development and seeks to attain domestic dominance and global leadership in a wide range of technologies for economic and national security reasons. In pursuit of this overarching objective, China has issued a large number of industrial policies, including more than 100 five-year plans, science and technology development plans, and sectoral plans over the last decade.1

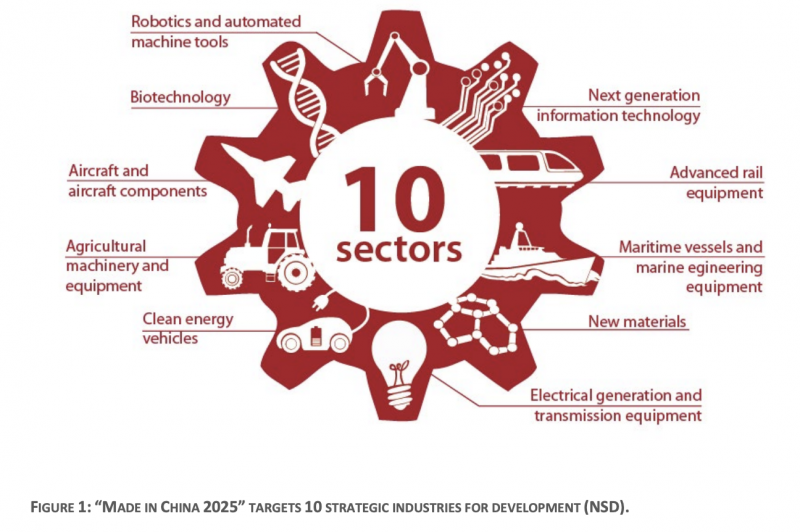

In 2015, China’s State Council released the “Made in China 2025 Notice,” a ten-year plan for targeting ten strategic advanced technology manufacturing industries for promotion and development: (1) next generation information technology; (2) robotics and automated machine tools; (3) aircraft and aircraft components (aerospace); (4) maritime vessels and marine engineering equipment; (5) advanced rail equipment; (6) clean energy vehicles; (7) electrical generation and transmission equipment; (8) agricultural machinery and equipment; (9) new materials; and (10) biotechnology. The program leverages the Chinese government’s power and central role in economic planning to alter competitive dynamics in global markets and acquire technologies in these industries. To achieve the program’s benchmarks, China aims to localize research and development, control segments of global supply chains, prioritize domestic production of technology, and capture global market share across these industries. In so doing so, China has committed to pursuing an “innovation-driven” development strategy and prioritizing breakthroughs in higher-end innovation. But that is only part of the story: “Made in China 2025” is as much roadmap to theft as it is guidance to innovate.

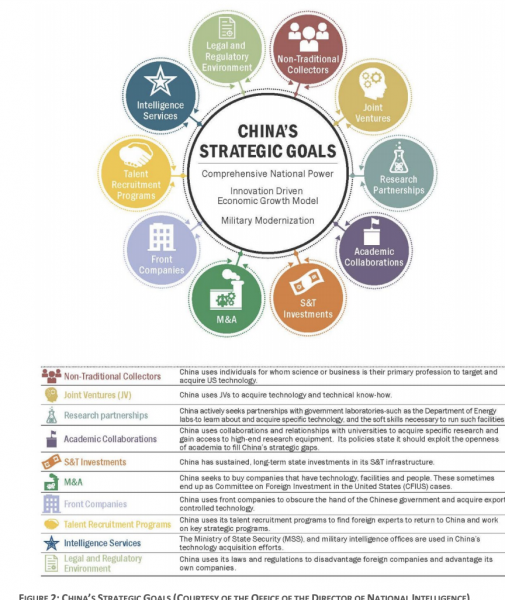

No one begrudges a nation that generates the most innovative ideas and from them develops the best technology. But we cannot tolerate a nation that steals our firepower and the fruits of our brainpower. And this is just what China is doing to achieve its development goals. While China aspires to be a leading nation, it does not act like one. China is instead pursuing its goals through malign behaviors that exploit features of a free-market economy and an open society like ours. As depicted in Figure 2 (and described in more detail below), China is using a variety of means, ranging from the facially legal to the illicit, including various forms of economic espionage, forced technology transfer, strategic acquisitions, and other, less obvious tactics to advance its economic development at our expense.

This multifaceted approach by China requires a whole-of-government response by the United States. While some of China’s tactics violate criminal laws, not all of them do, and even the violations may be difficult to detect and the offenders even more difficult to apprehend. For this reason, the Department must follow the same approach here that we follow with terrorism or classic espionage: we must cultivate traditional law enforcement responses (like investigations and prosecutions or civil suits) to disrupt specific actors while at the same time supporting other 4 departments and their authorities in a long-term, whole-of-government effort to raise the costs of bad behavior and advance the Administration’s national security strategy.

II. Economic Espionage and Trade Secret Theft

Espionage, as that term is traditionally used, involves trained intelligence professionals seeking out national defense information, typically contained in classified files. State-on-state spycraft conducted by intelligence services has existed for millennia, and we will continue to do our best to fight it. In fact, the Department now has three pending cases against former U.S. intelligence officers who are alleged to have spied for China—which is an unprecedented number.

But China now uses the same intelligence services and the same tradecraft—from co-opting insiders, to sending non-traditional collectors, to effectuating computer intrusions— against American companies and American workers to steal American technology and American know-how. Our private sector is at grave risk from the concerted efforts and resources of a determined nation-state.

Our recent cases bear this out. Over the course of just a few months, the Department’s National Security Division (NSD) and U.S. Attorney’s Offices across the country announced three cases alleging crimes committed by the same arm of the Chinese intelligence services, the Jiangsu Ministry of State Security, also known as the “JSSD.”

- In October, the Department announced the unprecedented extradition of a Chinese intelligence officer, Yanjun Xu, who allegedly sought technical information about jet aircraft engines from leading aviation companies in the United States and elsewhere. To get this information, he is accused of concealing the true nature of his employment and recruiting the companies’ aviation experts to travel to China under the guise of participating in university lectures and a nongovernmental “exchange” of ideas with academics. In fact, the experts’ audience worked for the Chinese government. Fortunately, thanks to swift action by one of the companies he targeted, we were able to identify Xu and build a criminal case while helping the company protect its intellectual property. And thanks to close cooperation from our foreign law enforcement partners in Belgium, where Xu traveled for business, we secured his arrest and extradition to the United States.

- That same month, the Department unsealed charges in another case targeting commercial aviation technology. According to that indictment, JSSD officers managed a team of hackers to conduct computer intrusions against at least a dozen companies, a number of whom had information related to a turbofan engine used in commercial jetliners. Meanwhile, a Chinese state-owned aerospace company was working to develop a comparable engine for use in commercial aircraft manufactured in China and elsewhere, and the stolen data could save the Chinese company substantial research and development expenses. And to accomplish their objectives, the conspirators successfully co-opted at least two Chinese nationals employed by one of the companies, who infected the company’s network with malware and warned the JSSD when law enforcement appeared to be investigating.

- Finally, in September, the Department charged a U.S. Army reservist, who is also a Chinese national, with acting as a source for a JSSD intelligence officer. According to the complaint in that case, the Chinese intelligence officer prompted his source (the defendant) to obtain background information on eight individuals, including other Chinese nationals who were working as engineers and scientists in the United States (some for defense contractors) for the purpose of recruiting them.

Our private sector finds itself the target of one of the most well-resourced nation-states in history and tactics that go far beyond the normal rough and tumble of capitalism. American businesses need the backing of the U.S. government to survive this threat.

As these cases also illustrate, to find what the Chinese are after one need look no further than the “Made in China 2025” initiative: from underwater drones and autonomous vehicles to global navigation satellite systems used in agriculture, from the steel industry to nuclear power plants and solar technology, from critical chemical compounds to inbred corn seeds. Chinese thefts target all kinds of commercial information, including trade secrets, as well as goods and services whose exports are restricted because of their military use.

From 2011-2018, more than 90 percent of the Department’s cases alleging economic espionage by or to benefit a state involve China, and more than two-thirds of the Department’s theft of trade secrets cases have had a nexus to China. To be sure, in this second category, there have been cases in which we did not have admissible proof that the Chinese government directed the theft. One example was the conviction of a Chinese company—the Sinovel Wind Group Company—for stealing wind turbine technology from a U.S. company resulting in the victim losing more than $1 billion in shareholder equity and almost 700 jobs, over half its global workforce. Another recent example was the conviction of a Chinese scientist for theft of genetically modified rice seeds with biopharmaceutical applications, providing a direct economic benefit to the Chinese crop institute that was the intended recipient of the seeds. And while we could not prove in court that these thefts were directed by the Chinese government, there is no question that they are in perfect consonance with Chinese government economic policy. The absence of meaningful protections for intellectual property in China, the paucity of cooperation with any requests for assistance in investigating these cases, the plethora of state sponsored enterprises, and the authoritarian control exercised by the Communist Party amply justify the conclusion that the Chinese government is ultimately responsible for those thefts, too.

In all of these cases, China’s strategy is the same: rob, replicate, and replace. Rob the American company of its intellectual property, replicate the technology, and replace the American company in the Chinese market and, one day, the global market. One of the best illustrations of this is the recent Micron case.

Until recently, China did not possess the technology needed to manufacture a basic kind of computer memory, known as dynamic random-access memory (“DRAM”). The worldwide market for DRAM is worth nearly $100 billion, and an American company in Idaho, Micron, controls about 20 to 25 percent of that market. In 2016, however, the Chinese Central Government and the State Council publicly identified the development of DRAM as a national economic priority and stood up a company to mass produce it. How did they set out to meet that goal? According to an indictment unsealed in San Francisco in November, a Taiwan competitor poached three of Micron’s employees, who stole trade secrets about DRAM worth up to $8.75 billion from Micron. The Taiwan company then partnered with a Chinese state-owned company to manufacture the memory. And in a galling twist, when Micron sought redress through the courts, the Chinese company sued Micron for infringing its patents, which were based on the very technology it is accused of stealing.

For now, we may have mitigated the damage to Micron. Days before our charges were announced, the Commerce Department placed the Chinese state-owned enterprise on the Entity List, which should prevent it from acquiring the goods and services required to manufacture DRAM based on the stolen trade secrets. And, in addition to the criminal indictment, we sued both the Chinese and Taiwan competitors, seeking an injunction that would bar them from exporting any products based on the stolen technology to the United States.

But the case has revealed gaps in the statutes we use to protect companies like Micron. For one thing, our ability to prosecute trade secret theft depends on having either a U.S. defendant or proof that an act in furtherance of the offense took place within the United States. 18 U.S.C. § 1837. Here, the defendants are accused of accessing trade secrets stored on Micron’s systems within the United States, but I can easily imagine circumstances where a U.S. company is robbed abroad, and criminal charges are unavailable here. And although one exMicron employee is accused of removing hundreds of the company’s files from its servers in the United States, without authorization and to benefit its competitor, and of running software to mask his activities, we could not charge him with a computer crime under Ninth Circuit precedent. See United States v. Nosal, 676 F.3d 854 (9th Cir. 2012).

III. Foreign Direct Investment and Supply Chain Threats

While theft is a major concern, it is not the only vector China can use to achieve its goals at the expense of our national security. Through its direct investment in U.S. companies and its sales of goods and services to our telecommunications sector, among others, China has sought to exploit our open markets for its national security gain. Both of these predatory Chinese tactics present a corresponding national security risk for the United States.

First, although we welcome foreign investment, we must be wary that what can be stolen can also, often, be bought. NSD’s Foreign Investment Review Staff represents the Department on the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), and the Committee’s work addresses the threat posed to our country through certain foreign investment from China where other U.S. Government authorities are not sufficient. China has been a rapidly expanding investor in the United States, becoming the largest single source of CFIUS filings in the last few years. While foreign direct investment helps our economy, some investments do pose an unacceptable national security risk.

Last year, for example, an investor owned and controlled by the Chinese government sought a $1.3 billion acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corporation, a chipmaker whose products are used by the U.S. government. The President prohibited the transaction, citing the national security risk posed by the deal. Earlier this year, the President blocked the attempted hostile takeover of the semiconductor and telecommunications equipment company Qualcomm by Broadcom. His action was based on the national security risks presented by such an acquisition, as detailed by the Department and others before CFIUS.

Technology transfer, particularly that which could violate export controls, can be a national security concern, but so can access to personal information, even that which initially appears to have no connection to national security. Increasingly, the Department has reviewed foreign investments with an eye towards protecting personal identifying information, health information, and other sensitive electronic information, which can be used to target individuals for espionage, especially if large datasets can be cross-referenced. As more devices are connected to the Internet, and more data is collected, it becomes possible to use that information for purposes never foreseen or intended. As one story from the last year illustrates, what looks like a map of fitness trackers might be a key to identifying national security installations; and the street you grew up on and the name of your first pet could be the clues to access your e-mail account (or more). Accordingly, as the Department has served as a co-lead agency in CFIUS in an increasing number of cases during this Administration, we bring to bear the Department’s understanding of how privacy, data security and integrity, and the rule of law can implicate national security in evaluating transactions for national security risk.

Second, we are increasingly concerned with supply chain threats, especially to our telecommunications sector. In July, the Administration recommended that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) deny an application by the indirect U.S. subsidiary of China Mobile Communications Corporation (a Chinese state-owned enterprise and the world’s largest telecom carrier) for a license to offer international telecommunications services in the United States, under Section 214 of the Communications Act of 1934. The Department led the national security and law enforcement review of the application, and the Executive Branch’s recommendation highlights the risks to U.S. law enforcement and national security from granting the indirect subsidiary of a Chinese state-owned-enterprise the status of a common carrier provider of telecommunications services. Such a status would give China Mobile access to trusted, peering relationships with American carriers.

In evaluating whether the China Mobile application was in the public interest, the Department considered a number of factors, including whether the applicant’s planned operations would provide opportunities to undermine the reliability and stability of our communications infrastructure, including by rendering it vulnerable to exploitation, manipulation, attack, sabotage, or covert monitoring; to enable economic espionage; and to undermine authorized law enforcement and national security missions. As the recommendation puts it, in light of those factors, “because China Mobile is subject to exploitation, influence, and control by the Chinese government, granting China Mobile’s [application] in the current national security environment, would pose substantial and unacceptable national security and law enforcement risks.”

IV. The Department’s China Initiative

As these prosecutions and other actions show, the Department has long taken the threat from China seriously and worked to confront it. But they also show the diversity and magnitude of the challenges we face and the need to prioritize our response. I will close by describing the purpose of the Department’s China Initiative and some of its principal goals.

Broadly speaking, the China Initiative aims to raise awareness of the threats we face, to focus the Department’s resources in confronting them, and to improve the Department’s response, particularly to newer challenges. I will chair a Steering Group, composed of my counterpart in the Criminal Division, Assistant Attorney General Brian Benczkowski, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Executive Assistant Director for National Security Jay Tabb, and five U.S. Attorneys, from Alabama, California, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas, to direct its efforts. We convened for the first time recently, and we have begun our work.

Investigating and prosecuting economic espionage and other federal crimes will remain at the heart of our work. We will ensure that these investigations and prosecutions are adequately resourced and prioritized. We will share enforcement approaches and best practices across the country. But as important as it is to investigate and prosecute trade secret theft like the kind I have described here, we must broaden our approach.

- First, we need to adapt our enforcement strategy to reach non-traditional collectors, including researchers in labs, universities, and the defense industrial base, some of whom may have undisclosed ties to Chinese institutions and conflicted loyalties;

- Second, we will work with U.S. Attorneys and their Assistants across the country to develop a broad outreach campaign to engage with companies, universities, and others in their Districts, both to raise awareness of the kinds of the threats I have described and to reinforce the trust that leads to cooperation with law enforcement and the enforcement actions I have described. (Congress, too, can help raise wholeof-society awareness through outreach to constituents, businesses, and universities.);

- Third, we will identify violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act by Chinese companies, to the disadvantage of American firms they compete with;

- Fourth, we will continue to work to improve Chinese responses to our requests for assistance in criminal investigations and prosecutions under the Mutual Legal Assistance Agreement we have with China; and

- Finally, as the Micron case shows, among others, in addition to making good cases, we must look for ways our investigations can be properly leveraged to support our federal partners’ tools, including economic tools available to the Departments of the Treasury and Commerce and the U.S. Trade Representative, diplomacy by the State Department, and engagement by the military and intelligence community.

The second prong of our China Initiative is focused on preventing threats from without, through foreign investments and supply chain compromises. The Administration was pleased to support recent legislation, the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), which adapts CFIUS to address current threats. We look forward to working with the Department of the Treasury to implement the newly launched pilot program under the statute, and to developing regulations to implement appropriately CFIUS’s expanded authority, and processes for the long-term success of the Committee in light of increased workflows. We must also work to reform the ad hoc process by which the Executive Branch advises the FCC on license applications, known as Team Telecom. Although I am pleased with the ultimate recommendation in the China Mobile matter, which sets an important precedent, we should continue to explore ways to make this process more efficient and expedient. Team Telecom reform is clearly needed. And we will work with our interagency and foreign partners on a strategy to ensure the security of our telecommunications networks as we transition to 5G.

Finally, we are cognizant that China’s game is a long one, and that it is working to covertly influence American public opinion in its favor. As the Vice President recently said, quoting the Intelligence Community, “China is targeting U.S. state and local governments and officials to exploit any divisions between federal and local levels on policy. It’s using wedge issues, like trade tariffs, to advance Beijing’s political influence.” At the Department, we are concerned that Beijing may use its economic leverage over businesses to covertly influence American policy, may covertly influence student groups on campus to monitor or retaliate against fellow students, or may exercise undisclosed control over media organizations in the United States, all without proper registration under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) and the accountability it brings. Under the Initiative, we will work to educate colleges and universities about potential threats to academic freedom and open discourse from covert Chinese influence efforts, raise awareness among the business community that acting as the covert agent of the Chinese government could trigger obligations to register under FARA, and continue to evaluate foreign media organizations for compliance with FARA.

In all of these efforts, we will be alert to ways that legislative reform may be helpful, and my staff and I would welcome the opportunity to work with the Congress on these issues.

Done well, our China Initiative will not only improve the way law enforcement responds to China’s economic aggression, but also will raise our country’s awareness of the threats and how we as a people can work to protect ourselves and our assets from them.

Even a whole-of-Executive-Branch effort will not succeed alone, however. We must work together with you in the Congress, as well as with the private sector, academic institutions, and foreign partners. For this reason, I am grateful to the Committee for providing me the opportunity to discuss these important issues on behalf of the Department, and for working with us to bring attention to and counter this national security threat. I am happy to answer any questions you may have.

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.