Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

Esotericism in the Late Ming — Early Qing Buddhist Revival

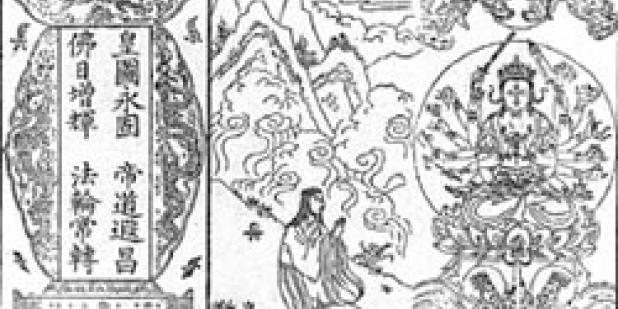

UC Berkeley's Center for Chinese Studies presents a talk by Robert Gimello on the Cundī literature and iconography of 17th century southern China and the importance of esoteric Buddhism during the 16th–17th century.

The goddess Cundī (准提, a.k.a. Saptakoṭi Buddhabhagavatī 七俱胝佛母) — held in Japan and in modern (but not pre-modern) China to be a form of Avalokiteśvara (觀音) — came to be a, if not the, central focus of esoteric Buddhist practice in late traditional Chinese Buddhism. She is still a significant presence in Chinese Buddhism today. The textual and iconographical foundations of her cult were established in the late 7th and early 8th centuries with multiple Chinese translations of the Cundīdevīdhāraṇī (e.g., 佛說七俱胝佛母心大准提陀羅尼經, T1077) and attendant ritual manuals (e.g., 七俱胝佛母心大准提陀羅尼法, T1078). Late in the 8th century, or early in the 9th, she was assigned a prominent place in the configuration of the Mahākaruṇāgarbhôdbhava maṇḍala (大悲胎藏生大漫荼羅王) — in the "Chamber of Pervasive Knowledge" (遍知院) and, especially in that latter capacity, she then made her way to Japan where her career would develop, in tandem with that of Cintāmaṇicakra (如意輪), in distinctively Japanese directions. The corpus of Cundī scripture in Chinese was expanded in the early Song with translations of the Kāraṇḍavyūha sūtra (大乘莊嚴寶王經, T1050), the Māyājāla tantra (佛說瑜伽大教王經, T890), and a fully fledged Cundī (Cundā) tantra (佛說持明藏瑜伽大教尊那菩薩大明成就儀軌經, T1169), but it was not until the late 11th century, in the Buddhism of the Liao 遼 dynasty, that her cult came truly into prominence and was given its classical formulation. That accomplishment may be credited especially to the monk Daoshen (道蝗) and his Xianmi yuantong chengfo xinyao ji (顯密圓通成佛心要集 Collection of Essentials for the Attainment of Buddhahood by Total [Inter-]Penetration of the Esoteric and the Exoteric, T1955), which treatise also served to "locate" Cundī in the broader Chinese Buddhist tradition by arguing for the deep mutual complementarity of Cundī practice (especially dhāraṇī recitation and visualization) with Huayan (華嚴) Buddhist thought. Daoshen's work was the mainstay of what came to be called "Cundī Esotericism" (准提密教) down to the 21st century. It is particularly noteworthy, however, that the development of the Cundī cult was not a steady and gradual process. There was an intriguing period of especially rapid acceleration in its growth, in southern China, at the very end of the Ming and the beginning of the Qing dynasty, that is to say, in the 17th century. From that one period and region there survive today, in the addenda to the Jiaxing Canon (嘉興大藏經) and in the Supplement to the [Kyoto] Buddhist Canon (續藏經), no fewer than six substantial texts devoted entirely to the exposition and interpretation of Cundī practice (弘贊。七俱胝佛母所說準提陀羅尼經會釋, SSZZ 446, 謝于教。准提淨業, SSZZ 1077, 施堯挺。準提心要, SSZZ 1078, 弘贊。持誦準提真言法要, SSZZ 1079, 受登 (a.k.a. 景淳)。天溪准提三昧行法, SSZZ 1481, 夏道人 (a.k.a. 埽道人默)。佛母淮提焚修悉地懺悔玄文, SSZZ 1482). Some of these texts include prefaces rich in pertinent historical information. Moreover, the extracanonical literature of the same period (e.g., 澹歸。遍行堂集, 袁黄。了凡四訓, etc.) also abounds in references to Cundī, and we have numerous examples of painted and cast images of the deity that appear to date from the same era. It is especially noteworthy that many of the figures revealed in this literature to have been most engaged in Cundī practice were also affiliated with the better known leaders of the late Ming Buddhist revival, i.e. with figures like Yunqi Zhuhong (雲棲祩宏 1532-1612), Hanshan Deqiing (憨山德清 1546-1623), Ouyi Zhixu (蕅益智旭 1599-1655), and their progeny. This talk will survey the Cundī literature and iconography of 17th century southern China and will draw attention to the fact that esoteric Buddhism — as well as Chan, Tiantai, and the challenges of Confucianism and Christianity — was an important part of 16th–17th century efflorescence of Chinese Buddhism.

Robert Gimello is an historian of Buddhism with special interests also in the Theology of Religions and in Comparative Mysticism. He concentrates especially on the Buddhism of China, Korea, & Japan, most particularly on the Buddhism of medieval and early modern China. The traditions of Buddhist thought and practice on which most of his work has focused are Huayan (The "Flower-Ornament" Tradition), Chan (Zen), and Esoteric (Tantric) Buddhism, in the study of all of which he is particularly concerned with the relationships between Buddhist thought or doctrine and Buddhist contemplative and liturgical practice. In the area of Theology of Religions, he is concerned chiefly with the question of what Catholic theology can, should, or must make of Buddhism. In the field of the study of mysticism he is engaged with debates about the differences and similarities among various mystical traditions and about the relationship between mystical experience and religious practices and beliefs. In addition to his previous employment at Dartmouth College, UC-Santa Barbara, the University of Arizona, and Harvard University, he has held many visiting appointments around the world. In the spring/summer term of 2010 he will serve as the Shinnyō-en Visiting Professor of Buddhist Studies at Stanford University. Gimello has served in the past as President of the Society for the Study of Chinese Religion, was a founding member of the Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism, and has recently joined the editorial board of the journal Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture. Among his current research/publication projects are: 1) completion of "Philosophy and the Occult in Later Chinese Buddhism: A Study and Annotated Translation of Daoshen's Xianmi yuantong chengfo xinyao ji (Essentials for the Achievement of Buddhahood in the Perfect [inter]Penetration of the Exoteric and the Esoteric)"; 2) preparation of a volume of essays entitled "A Flowering of Chinese Buddhism: Essays on the Huayan Tradition," co-edited with Imre Hamar and Frédéric Girard; and 3) completion of an annotated translation of Ŭisang's Diagram of the the Realm of Truth according to the One Vehicle of the Huayan Scripture.

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.