Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

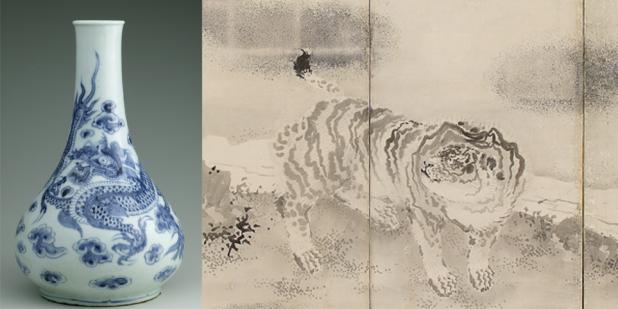

Dragon/Tiger

Significance of Dragons and Tigers as symbolism in East Asian art.

Dragons and tigers are ubiquitous in East Asian art. The two animals have been paired together since distant antiquity, with the earliest example coming from a Neolithic tomb in China, in which the shapes of both creatures were outlined in shells on either side of the deceased. With the development of cosmological theories on the order of the universe, dragon and tiger became associated with the active principle of yang and the passive principle of yin, respectively, and dragons were further related to spring and its life-giving rains, while tigers were connected with autumn and death. Appropriately, the dragon was assigned the color green, symbolic of new growth, and the tiger was assigned the color white, symbolic of the snow that brings the end (death) of the yearly cycle.

With the rise of an imperial government system in China, the dragon became identified with the Emperor, in particular the lofty five-clawed dragon, which often was limited in the arts to items used directly by the ruler. The introduction of Buddhism from South Asia added further nuances, as the Chinese term for dragon (long) was used to translate the South Asian word naga, mythical serpentine water spirits. Naga were capricious, but also connected to the historical Buddha through a story that a naga spread its nine-headed hood over him during a rainstorm. Similarly, dragons in China were auspicious images representing the yang energy of spring, but they could be terrifying, in the same way that a thunderstorm might be welcomed for bringing much needed rain to crops, yet feared for its destructive capacity. This symbolism spread from the Chinese mainland to the Korean peninsula and the Japanese archipelago, where it influenced the development of the arts at the same time that it acquired further culturally distinct nuances.

While the tiger was associated with the yin energy of autumn and death, it could also be a powerful protective symbol. In particular, as Buddhist eremitism developed in East Asia, and stories spread of famous monks who retreated to the mountains to meditate, tigers were often depicted as guardians of these holy figures. This tradition was particularly strong in Korea and Japan, where charming folk stories of tigers added new layers of meaning.

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.