Join us for a free one-day workshop for educators at the Japanese American National Museum, hosted by the USC U.S.-China Institute and the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. This workshop will include a guided tour of the beloved exhibition Common Ground: The Heart of Community, slated to close permanently in January 2025. Following the tour, learn strategies for engaging students in the primary source artifacts, images, and documents found in JANM’s vast collection and discover classroom-ready resources to support teaching and learning about the Japanese American experience.

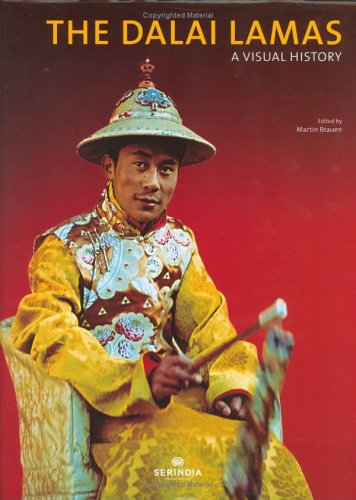

Brauen, The Dalai Lamas - A Visual History, 2005

Visual History of the Dalai Lamas

This magnificent book is the English version of the exhibition catalogue of "The Dalai Lamas," displayed at the Ethnographic Museum of the University of Zürich in early 2006.[1] The catalogue was originally published in German under the title Die Dalai Lamas: Tibets Reinkarnationen des Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (2005). The essays in this book provide what is arguably the most complete overview of the institution of the Dalai Lamas in a Western language. This alone would be enough to make this a  valuable contribution to the field of Tibetan and Buddhist studies. But the work is much more than written text and contains almost three hundred plates of exquisite tangkas, statues, and murals, as well as images of important historical documents and photographs. Taken together, these offer, as the subtitle promises, a "visual history" of the Dalai Lamas.

valuable contribution to the field of Tibetan and Buddhist studies. But the work is much more than written text and contains almost three hundred plates of exquisite tangkas, statues, and murals, as well as images of important historical documents and photographs. Taken together, these offer, as the subtitle promises, a "visual history" of the Dalai Lamas.

Martin Brauen--editor of the work and curator of the exhibition--is to be congratulated on a number of counts. Since many of the pieces whose images grace these pages are held in private collections, they are rarely seen in public. Brauen (and the institutions and collectors who gave their permission for these artifacts to be displayed) should be thanked for making these objects available to the scholarly community and broader public. In addition, the works selected for the exhibition were clearly chosen both for their beauty and for their importance as visual sources that illuminate the phenomenon of the Dalai Lamas. Finally, the publishers must be congratulated for the quality of the reproductions of the images, which is truly exceptional. In the case of the written documents--edicts, proclamations, inscriptions, and the like--the actual text is often legible, even when the formatting requirements render an image tiny. To put it succinctly, the visual part of this "visual history" is a veritable feast for the eyes.

In addition to the essays and artwork, the volume contains a two-page map of Tibet that shows where each of the Dalai Lamas was born. The book also comes with a folding insert that contains, on one side, a timeline of the Dalai Lamas, Panchen Lamas, regents, Mongol rulers, and Chinese emperors. On the other side, it contains beautiful reproductions of a series of seven lineage tangkas of nine Dalai Lamas and their previous incarnations (the subject of Per Sørensen's essay in the volume). The timeline, it seems to me, sets the standard for this type of work. Together with the map, it helps one to "visualize"--to put into perspective and to organize--the many details that are found in the essays.

The essays, written by well-known scholars in the field of Tibetan studies, are of two types: "biographical" essays on the fourteen Dalai Lamas and thematic essays. The latter treat such topics as the lineage of the lamas as a whole, the present Dalai Lama's hybrid modernist/traditionalist identity, the relationship of the Panchen and Dalai Lamas, the Dalai Lamas' protective deities, Western views of the Dalai Lamas throughout history, and the iconography of the Dalai Lamas. Many of these essays provide new and important information. Michael Henss's painstaking and important analysis of the iconography of the Dalai Lamas, Amy Heller's discussion of the Bektse cult, and Sørensen's close "reading" of the seven tangkas are good examples. Other contributions are more significant for their interpretive analysis. For example, Georges Dreyfus suggests that it would be a mistake to perceive the Dalai Lama as a strict modernist; Leonard van der Kuijp examines the importance of the 'Brom clan to the coalescence of the institution of the Dalai Lamas; Fabienne Jagou observes (although somewhat of an overstatement) that, because of age differences and average life spans, the Panchen Lamas made more of an impact on Tibetan history and culture than the Dalai Lamas (at least through the late nineteenth century); and, indeed, Brauen presents a fascinating discussion of how the Dalai Lamas have been the object of the Western gaze. Even the short essay on Tibetan epistolary style by Hanna Schneider, though arguably somewhat out of place in a volume like this, offers important information, including translations of the epistolary protocols for addressing the Dalai Lama, no small feat.

Taken together, the essays that survey the lives of the individual Dalai Lamas admirably accomplish the work that they set out to do. Each provides an overview of these figures, and a few also manage to touch on their literary achievements. Most also draw on original Tibetan texts. Although the authors are generally quite scrupulous about identifying their sources, in some instances they leave us guessing as to what their sources were, providing little or no information about the works they have consulted. Three essays, for example, have only a single endnote, suggesting, perhaps, an editorial oversight at some point. There is unevenness of another kind as well. In a volume such as this--which seeks to be accessible to a broad audience--the essays are most successful (or so it seems to me), when they balance three things: biography, hagiography, and historical context. They are least successful when they privilege one of these factors over the others. Hence, for example, something (the "magic," perhaps) is lost when an author sees his or her project as uncovering "just the facts" of a Dalai Lama's life. At the other end of the spectrum are essays that are content simply to rehearse the traditional hagiographies (the magic, without the facts). This approach offers minimal historical context--the broader social and political environment in which a particular Dalai Lama lived.

Finally, some contributors are exclusively preoccupied with that very context, and as a result it is the Dalai Lamas who then get "lost" in the details of the intrigues and power struggles of a given period. Of course, it is always easier to look with hindsight at the work of others and to make these kinds of judgments, quite another to be an author (or editor) struggling to balance these various factors while under the constraints of word limits and deadlines. So let me reiterate that as a whole the biographical essays provide a very adequate treatment of their subject matter. A few, however, go beyond mere adequacy, and succeed in achieving the kind of harmony I have just mentioned.

Of course, it is always possible to find a few inaccuracies in a work of this size. Doctrinal terms, and more specifically the Buddha's bodies, seem to confound a few of the contributors at more than one point. For example, van der Kuijp's claim that the "emanation body" of the Buddha, the trulku (sprul sku), "provides a basis for the various qualities associated with the sainthood of the bodhisattva" is a less than lucid characterization of this important notion (p.28). More problematic is Jagou's understanding of the sambhogakāya, the "blissful body" of the Buddha, which itself was, admittedly, somewhat problematically rendered into Tibetan by the term longku (longs sku), or longchö dzokpey ku (longs spyod rdzogs pa'i sku). Her transliteration of the term as lung sku, and her gloss (?) of it as "handle-like body," however, is baffling (p. 202). Equally baffling is her claim that "when Lopsang Chökyi Gyaltsen received the title Panchen Lama, the lineage of Ensa ended and a new one created," as if the first Panchen Lama's status as an incarnation of Ensapa Lobzang Döndrup (Dben sa pa Blo bzang don grub) had to cease, or to be negated, when he was given the title "Pan chen" (p. 281n1). A more minor point: Karénina Kollmar-Paulenz's claim that the third Dalai Lama (1543-88) was ordained by Mkhas grub Dge legs dpal bzang po (d. 1438) is of course impossible, although it is true that he was ordained by Dga' ldan khri zur Dge legs dpal bzang po. A final and more general observation: the system of phonetic rendering of Tibetan in the volume is not very helpful. It is at times inconsistent, and in some instances fails to come close to the way Tibetan words are actually pronounced.

These problems seem practically insignificant, however, in light of the mammoth achievements of this volume. The essays are informative, accessible, and at times insightful. The images are superb, and the visual aids amazingly useful. The exhibition was organized as a way of commemorating the Dalai Lama's seventieth birthday, and it is my understanding that the catalogue was presented to him at the opening as a birthday present. What a wonderful birthday celebration it must have been!

Note

[1]. This review was originally written for a volume on Dunhuang Tantric materials edited by Matthew Kapstein, to have been published as a special issue of Studies in Central and East Asian Religions (SCEAR). After problems arose with that publication, Kapstein negotiated for its release on H-Net, and we are delighted to be able to offer this excellent review on an important book.

Featured Articles

Please join us for the Grad Mixer! Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, Enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow students across USC Annenberg. Graduate students from any field are welcome to join, so it is a great opportunity to meet fellow students with IR/foreign policy-related research topics and interests.

RSVP link: https://forms.gle/1zer188RE9dCS6Ho6

Events

Hosted by USC Annenberg Office of International Affairs, enjoy food, drink and conversation with fellow international students.

Join us for an in-person conversation on Thursday, November 7th at 4pm with author David M. Lampton as he discusses his new book, Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War. The book examines the history of U.S.-China relations across eight U.S. presidential administrations.