In August 1939, China was partially occupied by Japan and India was part of the British empire. Jawaharlal Nehru went to China’s wartime capital in Chongqing and spoke on Chinese radio, saying, China and India “have been countries of yesterday, but the future bekons to them, and tomorrow is theirs.”

The end of World War II did not bring peace to China or India. In China, the civil war resumed, with the Communists eventually prevailing in 1949. In British India, independence forces mobilized, military units mutinied, and ethnic tensions rose. The British hurried to leave, hoping that the creation of a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan would satisfy most. The 1947 partition produced horrific communal violence and the desperate migration of millions.

Hoping to win Indian support in the Cold War and isolate the new government in China, in 1950 the U.S. reached out to Nehru, suggesting India replace China as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. The Indian leader rebuffered the invitation, not wanting to antagonize China. India insisted then that India’s membership on the security council ought not to be discussed until after Beijing was admitted to the UN. That, of course, would not happen for two decades.

India adopted Britain’s recognition of Tibet as part of China, but also hoped that Tibet’s autonomy and close ties with India would continue. In 1947, a soon to be independent India hosted a pan-Asian conference. Organizers welcomed delegations from China and from Tibet and had a conference map that distinguished Tibet from China. The Nationalist government of China protested and mention of the Tibet delegation was excised from conference materials and the map was recolored. Nehru’s government signaled then and later that it acknowledged Tibet as part of China. Chinese forces moved to occupy and control Tibet in 1951. India protested controls placed on its nationals and offices in Tibet.

India was a principal leader of the non-aligned movement among newly independent nations. It accepted arms from the Soviet Union, but fiercely opposed military alliances such as the one the U.S., the U.K., Australia and New Zealand formed with Pakistan and Southeast Asian nations. Beginning in 1954, India and China began promoting “five principles of peaceful coexistence” (mutual respect, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and peaceful coexistence). Nehru met with Mao, who praised the prime minister’s repeated assertion that Beijing be admitted to the U.N. The two agreed that their two large populations should be seen as a decisive asset, not a burden.

In the early 1950s, India’s government promoted its Buddhist heritage, publishing India-centric materials on the history of Buddhism in English, Hindi and Tibetan. The main target was likely the Buddhist border regions claimed by India. In 1956, India hosted a Buddhist conference. It included the twenty-one year old Dalai Lama, accompanied by Chinese officials. China’s Premier Zhou Enlai also visited as part of a trip that included other Asian capitals.

The Dalai Lama (b. 1935), Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) and Zhou Enlai (1898-1976) in New Delhi in 1956.

Nehru asked to visit Tibet in 1958. Beijing refused to permit it and built a road to Tibet through a region that India claimed as its own. Indian recognition of Chinese suzerainty over Tibet didn’t reduce Chinese worries, especially after the Dalai Lama and many followers fled to India in 1959. China suspected that India was cooperating with CIA-orchestrated efforts to weaken Chinese control over Tibet. The Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Daily began attacking Nehru and others in India for criticizing its actions in Tibet and for calling for the U.N. to consider the case. “So long as you do not end your anti-Chinese slander campaign, we will not cease hitting back,” the paper stated. “We are prepared to spend as much time on this as you want to.”

Meanwhile China’s rivalry with the Soviet Union was intensifying. Moscow pulled its specialists from China, including those working to develop its economy and to build its first nuclear weapon. At the same time, Soviet assistance to India was increasing. In 1955, the Soviets initiated a series of long term loans to help India develop its steel and other industries. They no doubt appreciated that India did not support a U.N. resolution condemning its invasion of Hungary in 1956. Following Sino-Indian border clashes in 1959, the Soviets gave India a $375 million line of credit for non-military purchases.

China launched its 1962 war with India after several border clashes. It acted out of long simmering suspicions of India’s aims towards Tibet and the contested regions. Some of these worries, on Tibet for instance, were probably unwarranted, but some were nourished by India’s policy of strengthening its hold in disputed territory. Roughly 7,000 Chinese and Indian soldiers were killed, wounded, taken prisoner or went missing. The month-long struggle poisoned relations between the two countries for decades. It helped create the all-weather friendly ties between Pakistan and China, that were later crucial when the United States and China sought rapprochement. The India-China rivalry was exploited by some in the region and others outside it for their own agendas. Chinese leaders see the U.S.-led “Quad” (U.S., India, Japan and Australia) as part of a long-standing effort to encircle and contain China. Once centered in the Himalayas and, as the 2020 border skirmishes show, still being played out there, the rivalry now extends to the vital sea lanes in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

In recent years, however, trade and other links between China and India have grown. Still, the two giants remain at odds over many things, particularly where one country ends and the other begins. They each have about 1.4 billion people, accounting for about a third of the world’s people. In the late 20th century, demographers anticipated that India would become more populous than China, but the gender gap, accelerating urbanization and growing affluence and education levels in China brought the expected moment ahead by two decades. As the population pyramid charts below illustrate, China is aging more rapidly as well. The median age in China is about the same as in the U.S. (38.4 years old), while in India it’s almost ten years younger (28.7).

These charts are based on data from the World Bank and the U.S. Census Bureau.

We’ll take up Chinese and Indian economic ties, their military expansions, and their stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the next newsletter. We hope you’ll join us and the World Affairs Council of Orange County on April 14 for a discussion with Nirupama Rao, former Indian ambassador to both China and the United States and author of an important book on India-China relations and the 1962 war. The 1939 quote from Nehru above is one she unearthed in the British archives. Ambassador Rao will share her assessment of the current state of ties between these giants. You may also wish to watch Rong Ying’s 荣膺 appraisal of the relationship. He’s one of China’s top scholars on India and for more than a decade has been vice president of the China Institute for International Studies, the Chinese foreign ministry’s think tank.

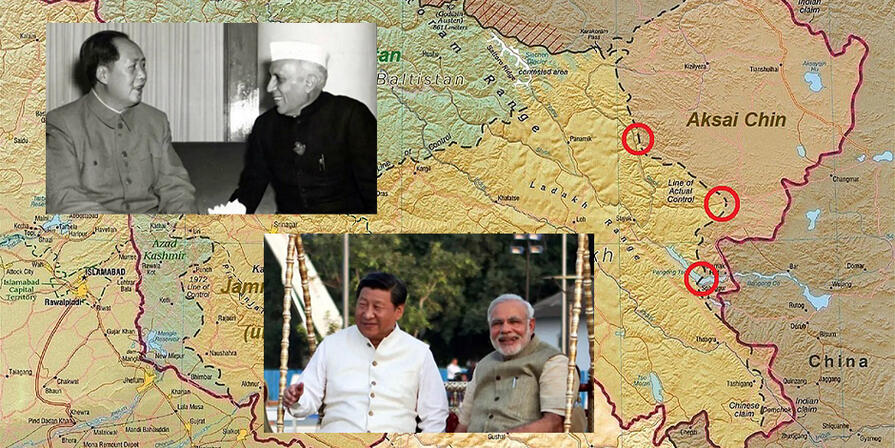

The featured image above includes photos above are of Mao Zedong (1893-1976) and Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) in Beijing in 1954 and Xi Jinping (b. 1953) and Narendra Modi (b. 1950) in Ahmedabad in 2014. The map in the background shows zones of contention on the border, including the sites of skirmishes in 2020.