Originally published on US-China Today on October 20, 2015. Written by Alexis Dale-Huang.

Those familiar with gender issues in China have likely heard about the discrimination infant girls face: from sex-selective abortions to child abandonment, the perils of being born female in China are real and immediate. As a result, international adoptions of Chinese girls have been on the rise since the early 1990s, with more than 71,000 babies being raised in U.S. households. Former TIME correspondent Melissa Ludtke is bringing these girls’ stories to light with her project, “Touching Home in China: In Search of Missing Girlhoods.” With the help of a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, Ludtke and her co-creators recently launched a vibrant multimedia website to give readers insight into some of the core questions these families wrestle with as their daughters come of age. This complements a curriculum on Chinese women and girls’ lives she has developed, along with six iBooks in the works. US-China Today interviewed Ludtke to learn more about the origins of her project, and where she hopes to take it in the coming years. What motivated you to focus on abandoned female babies in China and ultimately start Touching Home in China?

What motivated you to focus on abandoned female babies in China and ultimately start Touching Home in China?

Well, it’s interesting. One of the great motivating factors was that as soon as I adopted my daughter from China in 1997 I got engaged in learning so much about how she became my daughter. If you look into my past, you will see that I did a lot of reporting for TIME magazine on girls’ and women’s lives. So I’ve always felt incredible affiliation with the lives of girls and women, and really the struggles that women and girls in my lifetime here have and don’t have in common with those in China. So my daughter really was my inspiration.

How did you go about the process of reconnecting the girls in your story to their original hometowns?

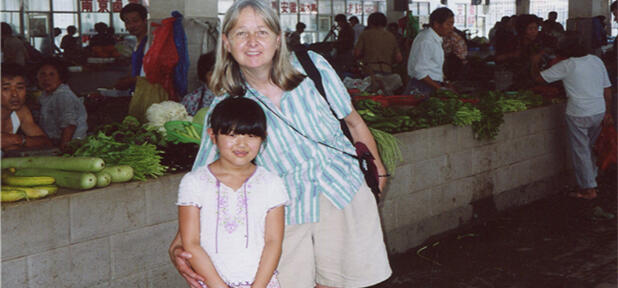

I took her [Maya, my daughter] back on our first homeland journey when she was seven, and we were very fortunate in that I had a number of people I knew who lived in China or knew people there. So we set up our own homeland tour, and at the end of that tour, we went back to her orphanage in Changzhou for a visit that we had arranged.

We did not go back to China again for a long time. In high school, she made the decision in ninth grade to study Mandarin. It gave her confidence, and she began to put pieces of her identity together. So I came to her one evening and said, “Maybe it’s time that you would like to go back to China. If you’re interested, I will try to find a way that you could meet girls there and spend time getting to know what your life would have been like.” A couple of days later, she said she wanted to go.

About a week or two later, we went to see the movie Somewhere Between with [the organization] Families with Children from China. Jennie, who had been Maya’s orphanage crib neighbor for nine months, also came to this film, and the two sat together during the screening and the presentation afterwards. About five days later, Jennie’s mother called me and said, “Jennie and Maya were talking about Maya’s trip back to Xiaxi. Jennie would like to go with her.”

Was this complicated? How long did it take to prepare everything?

I turned to friends of mine who are in China, and asked one of them to go to the towns and look for girls who were their [Maya and Jennie’s] age and who might be interested in becoming guides. They would be guides not because they were trained, but because they were the experts and had lived these girlhoods that Jennie and Maya were missing.

Before we were introduced to the guides, my friend sent us pictures and memos about the towns so Maya and Jennie would be prepared. That was in the spring of 2013, and we went back that August. They were about to start their senior year of high school then, and I think their level of maturity, what they could get from the experience, and what they could give to the girls there were really powerful.

Having studied the cases of many different girls, have you found that most young girls that were adopted from China have a desire to return?

I can only speak from my experience as a 19-year member of Families with Children from China in New England, so I know a lot of people from that as well as ones that are scattered throughout the country. The answer would be overwhelmingly yes. I know very few families that haven’t gone back to China in some way with their children. Most trips would be through organized homeland tours, and many of these tours give an add-on feature to return to the orphanages as a part of their tours.

The next level is young, mostly girls, that go back in search of birth parents with no paperwork. These children have been abandoned anonymously, so it is an exceedingly challenging emotional, as well as physical enterprise. There are documentaries that have been done on the Chinese and Korean adoptive experiences, but they usually focus on the birth parent search. So the project that we set out to do is a very rare experience.

In your newest iBook, Daughter. Wife. Mother., you mention that a woman’s role in the family is rapidly changing. What kinds of changes are you referring to?

One of the things you discover is irony – the One Child Policy that led to me raising Maya, has led to more families raising girls as only children.

When you raise a girl as an only child, your resources go solely to that girl. In China, those funds often went to sons, because families believed their daughter was going to be the outside daughter [in China, traditionally the daughter, once married, lives with the husband's parents] as soon as she got married. Now you have a generation, especially in Jiangsu province where Maya and Jennie came from, where every family is restricted to one child with a few exceptions.

What does this mean? This means they are graduating from high school and college, and all of the resources, attention, and determination for them to succeed is going to them.

However, cultural traditions still push on them, through government messages and the traditions of families after they graduate from college. So you have this change brought about by the educational advancement of women, but you find that traditional attitudes towards women are very much in play as they move into their work lives.

What kinds of lessons are you thinking about teaching with your project? Are you hoping they reach schools in the United States and China?

It’s going to be more difficult for them to reach China. The Chinese curriculum is rigid, and this is not necessarily the thinking and deep inquiry that schools in China look for.

In terms of here, I need to find the right person to partner with to write this curriculum. I was surprised to learn how many educators that teach lessons on China are desperately looking for curriculum on the One Child Policy. Our first chapter, Abandoned Baby, would certainly fit that. It begins to raise questions about gender and, with its timeline from 1949 to 2014, shows fertility rates in China for each year. This is the first time in which you have a resource for school that puts the One Child Policy into a broader historical context.

Meanwhile, in the Touching Home chapter, it introduces the story of the American girls arriving and meeting the girls who will be their guides. This leads to questions of identity such as, ‘How do I define identity? How do you figure out who you are?’

What is one thing that you want your readers or viewers to take away from your project?

I firmly believe this is not a story only for Chinese adoptees. It has far more resonance, and I think it is being well received by communities of families with children from China. I really believe, through the experiences that I have had, that there will be people who can relate to this that have nothing to do with adoption and have never been to China.

We are constantly trying to understand China better as a nation. We often see it through the geopolitical lens or the military lens, so we took it through the lens of girls’ lives at a more personal level. I’ve always believed that if you tell a good story, people will come.

What are your future plans or hopes for your project? How could those that are interested in the story contribute or possibly learn more about it and do more research on their own?

I am hoping that we will have the iBook series published within a year. We will also be moving all of that content onto our website, making it globally accessible. I also hope we have the curriculum built within a year, so we can get it into classrooms. And as a part of my Henry Luce grant, we have a portion to partner with an educational outreach person who will teach us how make teachers aware of our curriculum.

I also have a student intern that keeps journal articles, reports, and broadcast videos that relate to the topics. With these, we will make a curated link library of resources that are associated with each of our stories and our curriculum. In addition, we maintain a Facebook page devoted to topics of women’s and girls’ lives, a Twitter feed, a YouTube channel with our videos, and an Instagram account.

These girls who are now in their teen years and moving in through college are really an extraordinary bridge between America and China; this project is just one of the portions of the bridge between our countries and cultures.