Originally published by US-China Today on June 22, 2017. Written by Huitong Zou & Kelly Qiu.

I swallowed an iron moon, we call it a screw

I swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms

Bent over machines, our youth died young

I swallowed labor, I swallowed poverty

Swallowed pedestrian bridges, swallowed this rusted-out life

I can’t swallow anymore

Everything I’ve swallowed roils up in my throat

I spread across my country a poem of shame.

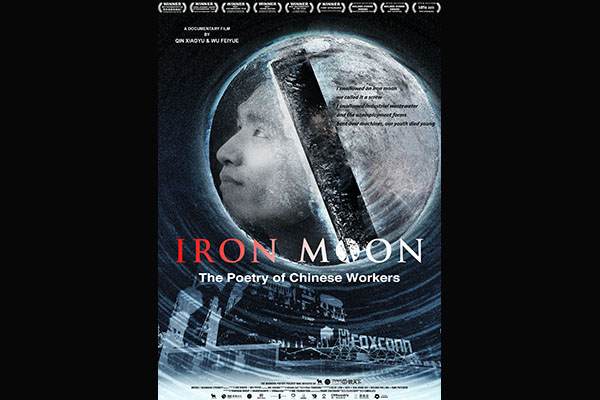

These words were written by Xu Lizhi, a 24-year-old migrant worker who committed suicide in 2014 due to the grueling and harsh working conditions at the Foxconn factory in Shenzhen. His haunting poem is not only featured in the title of Iron Moon, a documentary that won the best documentary category in several of China’s film festivals, but also serves as a centerpiece of the film that grapples with the moral dilemma facing contemporary China in an age of economic prosperity. Following the lives of working class migrants — Blackbird, Lucky, Dawn, Old Well and members of the Xu Lizhi family — Iron Moon presents a heartbreakingly honest tale of the lives of China’s industrial workers and how they use poetry to express their pain and be heard in a sea of muffled voices. US-China Today spoke with the director of Iron Moon, Xiaoyu Qin, to discuss the vision and stories behind the evocative documentary.

What was your inspiration for the film?

I was one of the judges at the 4th Poetry International Festival Rotterdam in 2013. The organizers would pick up poems from ArtsBeijing.com, translate them into English and post on their website. The poem “Going Home on Paper” was the best received.

I was shocked that this unknown poet won. As the author of “Jade Ladder: Contemporary Chinese Poetry,” I feel qualified to speak on the field of contemporary poetry. Yet I had never heard of Jinniu Guo, the poet behind “Going Home on Paper,” and was even more surprised to find out that Guo was a migrant worker who had worked as a construction worker, porter and store keeper in the Pearl River Delta. I recounted Guo’s story in an article titled “Moment of Poetry.”

In 2014, Xiaobo Wu, a financial writer in China, discovered this article. In his book “30 Year Storm,” he described the 30 years after Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening up” from an entrepreneur’s perspective. Wu realized that there are many working-class poets in today’s China, and that they continue to work at the front lines while writing poems about life and work.

Wu suggested that we compile a selection of the workers’ poems to record this history. I started creating “My Poetry: Collection of Poems of the Contemporary Working Class.” Wu later met with Feiyue Wu, the director who helped him with the documentary “30 Year Storm.” These two and I then started filming “Iron Moon,” to tell the stories of these working-class poets.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while filming “Iron Moon”?

There were plenty of difficulties. For instance, lack of funds was the main challenge. For some scenes we had to film in a coal mine. These scenes were particularly sensitive and had high safety risks, and it was difficult communicating with the mine’s management. The business owners of the coal mines were reluctant to let us film. Once we got into a mine, we saw that the tunnels inside had been created bit by bit with several rounds of explosives, so the structure was not stable and very dangerous. This happens whenever you are filming something in the documentary world. There are always inevitable risks for us, but we have to take them. Actually, the scenes that were fraught with difficulty have the most value and add depth to the film.

Documentaries’ plots often emerge during the editing process. Was this the case for “Iron Moon”?

We probably shot more than 10 worker poets and gradually formed our ideas during the process. We then picked six of them to include in our final film. These six workers represent diverse backgrounds: men and women; migrant workers and factory workers already living in the big cities; ethnic minorities; and workers with ages ranging from 20 to over 50. These six worker poets’ lives represent the lives of working class poets, and are both intriguing and enlightening. For instance, Nianxi Chen, who has worked in a gold mine his entire life, can be seen as the first in 2,000 years of poetic history to incorporate his own experience of digging in mines into the creation of poems. If he hadn’t written about his experiences, they wouldn’t have been addressed in literature. Lives like his thus spark the audience’s curiosity and they’re enthusiastic to learn what these workers’ lives are really like. So if the audience is moved by their stories and obtains a deeper perspective on their lives, we will feel that we have fulfilled our original intention.

To make a long story short, we hope that by presenting the lives of these six worker poets, all of whom represent the face of Chinese workers, we will be able to outline the lives of working people in China and make everyone better understand their situation. If viewers lack understanding of this group of people, we hope this film can spark conversation on the situation. Our original intention has been to extend the meaning of the film and make it more than just a piece of literary work.

“Iron Moon” exposes us to the hardships of China’s working class. What policies should society adopt in order to address this issue?

I think our focus is more on the extraordinary creativity of the Chinese working class rather than their hardships. Since they are regarded as “the silent majority” of society and are ignored, we hope this film will alter the stereotypical image that society has projected on them. The film inevitably illustrates the hardships in their lives. I am not a policy maker; I am just a director, so I cannot give specific policy recommendations. But if “Iron Moon” can initiate concern for this social group and then facilitate positive changes, we would be glad to see it happen. We think that in order for a society to function, there needs to be understanding and dialogue between all levels of society, and we think “Iron Moon” can provide an opportunity for this.

Some portions of the film have a critical lean to them. Were you concerned about government censorship because of this?

We had to pass a censorship examination in order to release the film. We decided to take it optimistically, meaning that we accept minor adjustments or cuts to ensure that the film would reach the public successfully. It would be a huge loss for both the film makers and the society if we insist on retaining everything we made. Fortunately, we chose to express our thoughts through poems. It is subtle and takes time to understand the deep meaning behind them. So it is far better than bare criticism.

As a filmmaker, do you find yourself having to compromise your art for commercial success?

First of all, we do not reject commerce. I think film is a commodity -- a cultural commodity. There are some entertainment films produced just for commerce; their cultural attributes and visual aesthetics are rather superficial. They are nothing more than commodities, existing just to stimulate our senses and emotions. Yet genuine literary work is far more than that. They are created from the heart, will broaden your horizons, and will push you to think. So I think that the few outstanding films do not necessarily need to shy away from being a commodity, but they still want to pursue genuine social and aesthetic values. We hope that the film we create will have a kind of “poetic and sincere” power. Thus a lot of movies don’t want to be categorized as commercial or non-commercial films, because they actually are all commodities, but some are more successful in the box office while some possess higher artistic value. Yet I think films can still be judged on a scale of good and bad, or outstanding and terrible. Personally, I prefer watching outstanding, thought-provoking films that will deepen my thoughts and enrich my life.

Where do you see Chinese documentary filmmaking going in the next couple of years?

One trend we can see is that more and more documentaries are being shown in theaters. This includes “Himalaya: Ladder to Paradise” last year, “A Bite of China” earlier this year, “Born in China” this summer and more recently, “Masters in Forbidden City” and “This is Life.” But even though “Iron Moon” won an award two years ago at Golden Goblet Awards and received two more awards afterwards, for a long time issuing corporations were not confident about releasing the film to the public. I think this is a current issue that documentaries face in China.

At the same time, we do see more documentaries entering movie theaters and exploring new ways to reach the public. For example, “Iron Moon” tried crowdfunding for one year before it was successfully shown in the theater. I think there are two lines of reasoning behind these changes: first, film audiences are becoming more and more interested in the industry, are getting tired of commercial films, and are seeking films of higher quality and individuality. Compared to commercial films, documentaries provide a greater sense of reality and power - providing a relatively new experience for the audience. On the other hand, the Internet has given us new tools. We are able to use not only WeChat, Weibo and other types of platforms, but also use new methods such as crowdfunding, paving the way for documentaries to reach the public.

The Internet era has given documentaries a new set of opportunities. People were unfamiliar with documentaries in the past, but are now able to raise funds for documentaries online, or even completely create films (like “Life in A Day” was filmed and edited by netizens) on the Internet, interact directly with the audience and promote our works. If we fully make use of the advantages, it is possible for us to take the Chinese documentary industry to a new level.

“Iron Moon,” your directorial debut, has done extremely well. Where do you see yourself going as a director?

Our next project is also a documentary. We would like to make “Iron Moon” a trilogy, and are busily filming and editing the other two. They will have poems as well, but we will also incorporate relevant elements and fields such as the new rural construction and the “laid-off tide” of coal and steel workers during the process of De-Capacity. We hope to increase attention to these issues through our films.

We are also shooting a film about hospice care. To be more specific, it would be about the experience of a girl in her 20s in a hospice care hospital, and would focus on her personal growth. We want to bring attention to China’s aging problem and death - something that everyone will meet one day. Another other documentary we are working on is about children in Xinjiang. We would like to present an original and genuine Xinjiang, showing the innocence of children and the harmony between humans and the natural world.

Why did you choose to focus on the plight of Chinese migrant workers?

Because they make up a huge portion of Chinese society, and have contributed and sacrificed a lot for China’s rise over the last few decades. However, their living conditions and salaries are terrible. So we believe if more films and books can focus on the working class, it would bring attention and help them. This kind of literary work is important, because in this era, you can say that this group of people’s future can determine the direction in which China is going. The prosperity of the whole country depends depends on the well-being of its working class. If they are able to live well, the whole society would prosper. Otherwise, there will be serious social problems.

What is the main message you hope to convey through your film?

What is the main message you hope to convey through your film?

As [philosopher] Walter Benjamin once said, “It is more difficult to memorize the nameless than celebrities.” The history is the memory created to commemorate the nameless. Nianxi Chen, one of the working-class poets we chose, also noted that even the humblest spine has its own universe. This film is a gift and a valuable memory for the humble and nameless.

We think that Chinese workers made not only the economic miracle for China, but also countless poems for the literal world. Outstanding ones are just as great as those written by famous poets, and are sometimes even better because they are deepened by the poets’ own experiences, thus deeply touching our hearts. It is a pity to neglect and underestimate their value. “Iron Moon” is unveiling the “silent majority” of Chinese society. They showed their mental power through their poems and life clips. These poems are the words of people living at the bottom of the society and are of great values to history and literature. We want to spread their words further, push people to think about the working class because we believe that serves as a catalyst to improving society.

I was one of the judges at the 4th Poetry International Festival Rotterdam in 2013. The organizers would pick up poems from ArtsBeijing.com, translate them into English and post on their website. The poem “Going Home on Paper” was the best received.

I was one of the judges at the 4th Poetry International Festival Rotterdam in 2013. The organizers would pick up poems from ArtsBeijing.com, translate them into English and post on their website. The poem “Going Home on Paper” was the best received. I think our focus is more on the extraordinary creativity of the Chinese working class rather than their hardships. Since they are regarded as “the silent majority” of society and are ignored, we hope this film will alter the stereotypical image that society has projected on them. The film inevitably illustrates the hardships in their lives. I am not a policy maker; I am just a director, so I cannot give specific policy recommendations. But if “Iron Moon” can initiate concern for this social group and then facilitate positive changes, we would be glad to see it happen. We think that in order for a society to function, there needs to be understanding and dialogue between all levels of society, and we think “Iron Moon” can provide an opportunity for this.

I think our focus is more on the extraordinary creativity of the Chinese working class rather than their hardships. Since they are regarded as “the silent majority” of society and are ignored, we hope this film will alter the stereotypical image that society has projected on them. The film inevitably illustrates the hardships in their lives. I am not a policy maker; I am just a director, so I cannot give specific policy recommendations. But if “Iron Moon” can initiate concern for this social group and then facilitate positive changes, we would be glad to see it happen. We think that in order for a society to function, there needs to be understanding and dialogue between all levels of society, and we think “Iron Moon” can provide an opportunity for this.

What is the main message you hope to convey through your film?

What is the main message you hope to convey through your film?