Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get them delivered straight to your inbox!

The COVID-19 pandemic reconfigured human activity across the globe. Differing political systems, priorities and social norms have yielded significantly different outcomes between China and the U.S. and within the two countries. Ahead of our two upcoming webinars (today with Lucy Hornby of the Financial Times, on Tuesday with a US Heartland China Association panel of Chinese and American public health experts), we offer this quick look at the varied responses and outcomes to the challenge of covid-19.

In early December 2019, a patient in Wuhan sought medical help for pneumonia-like symptoms. By the end of the month, Wuhan Municipal Health Authorities reported a string of these pneumonia-like cases in the city and, on January 3, 2020, China officially notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of a pneumonia outbreak. At that time, the heads of the Chinese and American centers for disease control talked about the outbreak. By this time, Wuhan authorities had shuttered the market thought to be the source of the virus. Local authorities also reprimanded several medical personnel for posting unauthorized information about a new SARS-like disease. Dr. Li Wenliang was among them and in a written statement he acknowledged that he could be punished if he posted such information without permission. He was among the first to die from covid-19. As China’s lunar new year holiday approached, China’s largest media outlets focused on the work of Communist Party Secretary-General and State President Xi Jinping. In Wuhan, officials permitted life to go on as normal, including a famous potluck banquet attended by tens of thousands of residents. In the U.S., the CDC warned against travel to Wuhan. Chinese scientists determine the genetic sequence of the virus and share it via the net, allowing scientists worldwide to study it. Human to human transmission was confirmed.

Chinese state media begin focusing on the outbreak. On Jan. 23, CCTV included a call to action in the widely-viewed “Spring Festival Gala.” That same day Chinese authorities shut down transportation within Wuhan. People are barred from leaving the city. The restriction on movement is gradually expanded to include tens of millions of people. By this time, 17 had died, though the Chinese government subsequently adjusted the number of cases and deaths upwards. Hospitals in Wuhan were soon overwhelmed, medical personnel were rushed in and construction crews worked to erect new buildings to accommodate the rush of patients.

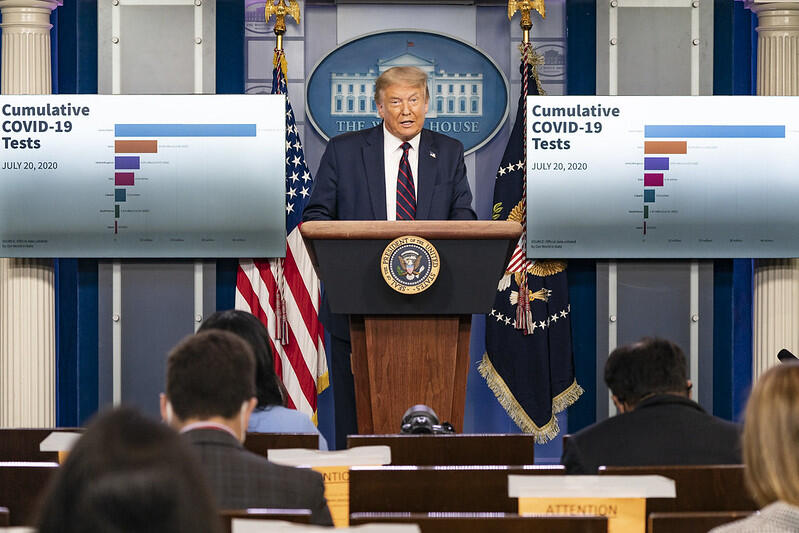

The U.S. CDC confirmed on Jan. 21 the first domestic case of the novel coronavirus, an individual who returned to the U.S. from Wuhan a week before. In Davos for the World Economic Forum, President Donald Trump assured an interviewer that the U.S. had the threat under control. Cases in the U.S. emerged in several locations, including a Seattle nursing home and a cruise ship in San Francisco. On Jan. 30 WHO declared the outbreak a global health emergency. The next day, Pres. Trump imposed a ban on visitors who had been in China within two weeks from entering the U.S. American citizens, residents or their family members were exempt. By this time, however, the virus had spread to other parts of Asia as well as Europe. Screening of passengers was limited and haphazard. The initial covid-19 test developed and distributed by the CDC was eventually found to be flawed due to contamination in the CDC lab.

In China, central and local authorities moved to restrict movement far beyond Wuhan. Most people in China’s cities were directed to shelter in place and were only permitted occasional trips to secure groceries. Delivery services, already robust, expanded. Mask wearing, already a norm for many, became mandatory. Temperature screening was imposed at shops, residential complexes, and other locations. Those thought to be infected were quarantined, often away from their families. City streets were nearly deserted and much of China’s economy, including the global supply chains tied to it, ground to a standstill.

These measures were often described as draconian, but over two months largely worked to contain the virus and keep health system from collapsing. During this time, Taiwan and South Korea, both tightly tied to the Chinese economy, imposed vigorous detection and quarantine measures and also contained covid-19. Neither shut down public transit or imposed a full lockdown. As in China, South Korea and Taiwan employed tech tools and active contact tracing and isolation monitoring. Again as in China, people in both countries already had the habit of wearing face coverings to prevent the spread of viruses and readily complied with mask mandates as public transit systems ramped up cleaning routines. As China made progress against the disease, it ramped up its internal and external propaganda efforts to trumpet its successes and highlight problems elsewhere.

Health experts, including those working for the U.S. government were alarmed at how covid-19 was spreading here and elsewhere. On Feb. 26, Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters “the disruption to everyday life might be severe.” In short order, U.S. stock markets plummeted. Masks and other protective gear were in short supply. Shoppers began emptying store shelves of food staples, cleaning supplies and toilet paper. Experts encouraged social distancing, hand washing, and avoiding crowds. Some advocated wearing face coverings. Worried that a run on masks might make supplying health care and first responders difficult, Anthony Fauci said most people didn’t need them. Visiting the CDC on March 6, Pres. Trump praised the agency for starting work to combat the virus “before anybody ever heard of it.”

On March 13, Pres. Trump declared a national emergency, but did not issue national guidelines. By this time, New York had over half of all the confirmed cases in the U.S. By the first week of April, governors of 42 states had issued stay at home orders, covering, 95% of the American population. In New York, the lockdown eventually slowed the rise in cases. From a peak of over 12,000 new cases on April 3, New York cut the daily increase in half by April 22 and is now averaging about 700 new cases a day. In California, “the curve” began to flatten in April, but has risen since then and spiked up in late June and July. California is now averaging 10,000 new cases a day. Adjusting for population size several states are doing worse than California.

By mid-March, Chinese and U.S. leaders and diplomats were offering up unproven theories of covid-19’s origin and spread. PRC Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijun tweeted, “It might be US army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan.” Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo started calling the disease the “Chinese flu” or the “Wuhan virus.” In June, the President used the term “Kong flu.” On March 26, Pres. Trump sought to reassure the country, “we’re doing a great job with it. And it will go away. Just stay calm.”

China was beginning to reopen, though many people were worried and hesitant. It’s economy is starting to recover though many, especially migrant workers, aren’t yet back at work.

It was only in early April that the U.S. CDC began promoting masks as a voluntary measure when people could not practice social distancing. Pres. Trump resisted wearing a mask in public until last week. Rather than being universally understood as an individual effort to prevent the spread of covid-19, mask wearing became part of America’s political/cultural struggles. Recognizing that a clear universal standard served their corporate needs and the public interest, many of America’s largest companies instituted face covering requirements.

The outbreak started in China, took thousands of lives there, and produced China’s first economic downturn in decades. There are still travel restrictions in place (and concern about the disease being reintroduced from abroad is hampering the return of more than 1,000 U.S. diplomats and their families to China).

In the U.S. however, the decentralized and inconsistent response to the covid-19 remains a work in progress. In some states, governors and mayors are at odds over restrictions and mandates. More than 143,000 people have been killed by the disease and tens of millions remain unemployed. Trillions of dollars of federal spending has staved off an economic meltdown, but recovery remains uneven and uncertain. This week Pres. Trump warned that things will get worse and encouraged mask wearing.

The Wall Street Journal reported a possible bright spot. In the southern hemisphere, where the traditional flu season is underway, measures taken to keep covid-19 at bay have also reduced the spread of other viruses. This fall, doing the right things to contain covid-19 could help people in the northern hemisphere avoid more traditional flu strains. Vaccine development efforts in many countries are well underway and should eventually help stem the spread of covid-19. But the outbreak in the U.S. has exacerbated inequalities and tensions. Some people of Asian descent have been subjected to racist language and even physical assault. And the disease has been especially destructive in Latino and Black communities and the poor have experienced the greatest economic pressure.

U.S.-China relations are obviously frayed. The U.S. has ordered the closure of China’s Houston consulate. China has vowed to retaliate. The FBI says the San Francisco consulate is harboring someone it believes concealed her links to China’s military in getting a visa to the U.S. and working at a California university. The trade pact signed in January may be in jeopardy. But the covid-19 pandemic demonstrates that greater cooperation is essential to combat shared challenges.

Watch this space.

And please join us for our upcoming webinars.