Originally published by US-China Today on September 15, 2021. Written by Caleb Huang.

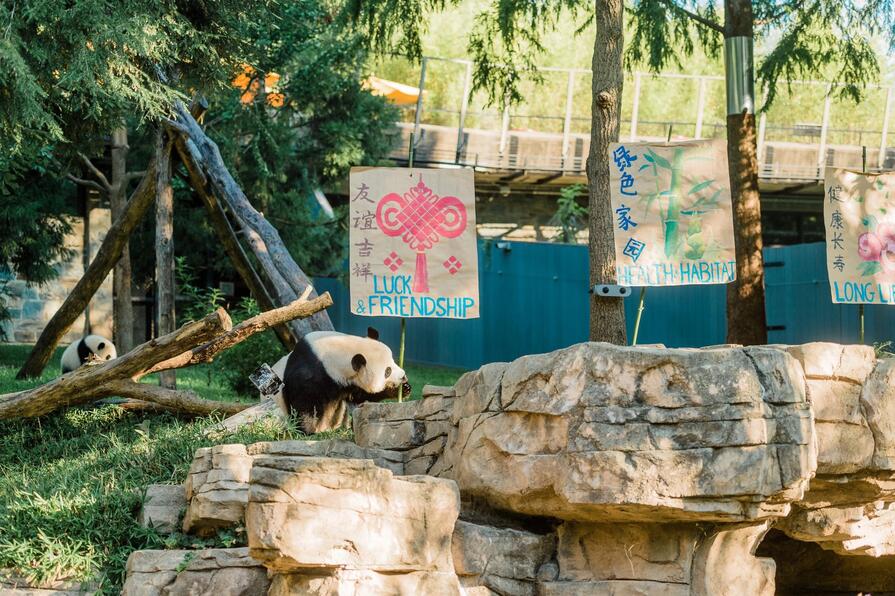

Pandas at the San Diego Zoo, the 2008 Olympics Games and Chinese state media on Youtube all have one thing in common: they are displays of Chinese “soft power” that aim to foster positive views of China among foreigners. These are only a few high-profile examples of a campaign to challenge existing perceptions about China and win hearts and minds around the world.

The outbreak of COVID-19, which originated in Wuhan, China, has thrown a wrench in this plan and drastically lowered the international favorability of the Chinese government. According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 14 different countries, a median of 61 percent of respondents say China has done a bad job dealing with the outbreak. Confidence in China’s president, Xi Jinping, also fell drastically in surveyed countries — the poll shows a median of 78 percent of those surveyed have little or no confidence in the leader.

However, recent events and politics may suggest that the Chinese government’s primary concern is its own citizens and not global perceptions. In this time of international unpopularity, China remains more focused on maintaining a stable domestic image than using soft power to furnish global popularity.

What is Soft Power?

Soft power, a term coined by Harvard University Professor Joseph S. Nye Jr. in 1990, is the means by which a country gets other countries to “want what it wants”. In contrast to hard power tools, like diplomatic envoys, military power and geopolitical leverage, soft power is the values and ideals a country promotes. Soft power is an important tool for countries to attract tourism, business and international students and also boosts credibility by allowing one country to persuade another country to follow its lead.

Historically, soft power has not been China’s strongest attribute. The 2019 Soft Power 30, an index created by Portland Strategic Communications Consultancy and the USC Center on Public Diplomacy to measure the soft power of 30 countries ranks China 27th on their list. The index lists China far behind countries such as France, the United Kingdom and the United States, which rank first, second and fifth respectively. Furthermore, China lags behind regional rivals such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore who rank eighth, 19th and 21st respectively.

The summer protests of 2019 and the ongoing subsequent crackdown on Hong Kong pro-democracy demonstrations have damaged China’s international image. Further human rights abuses of the Uighur ethnic minority group in the Western province of Xinjiang have had a similar effect on the international stage. These extensive campaigns have reinforced an international perception of China as repressive and heavy-handed.

Joshua Kurlantzick, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, notes that it is difficult to erase people’s views of China given its past actions.“Broad global views are shaped by how China has acted in the last year or two,” Kurlantzick says. “I don’t think you can necessarily just remove that by giving a few countries pandas. You can change people’s views probably over time with an effective soft power campaign, but they need to be connected to some sort of reality.”

Some critics argue that China is not able to project soft power as effectively as other countries. Nathan Park, an East Asian politics and economics expert, has written in a Foreign Policy article that “China is bad at soft power.” China has not been successful with using soft power at any point “in the past ten years. The thing that came the closest was the Three Body Problem (三体), novel. But that really was more of an outlier,” Park says. Buy and large, China has lagged far behind other countries in utilizing soft power as a tool of statecraft.

Effects on Global Ambitions

In the past few decades, China has paid increasing attention to the image it portrays to the world. China began to invest in soft power when former President Hu Jintao pushed for it in an address to the 17th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in 2007. In 2014, President Xi expressed similar sentiments, stating, “We should increase China’s soft power, give a good Chinese narrative and better communicate China’s message to the world.”

“[China] thinks [soft power] is a valuable way of persuading other countries, generally boasting their public image in other countries and it can have a generally positive effect on other countries and at some point, aligning with the state’s policies,” says Kurlantzick.

China’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic has been strongly criticized

According to David Shambaugh, a leading sinologist at George Washington University, China is expected to spend $10 billion a year as part of its soft power campaign. Experts feel China is aware that its increasing economic and military might are not enough to lead and attract the world. “[Economic and military power is] more effective if you combine that with soft power,” says Joseph Nye, professor of international relations at Harvard University, in an interview with China Power.

In recent years, China’s focus has been on extending its economic influence abroad. Beijing has funded investment projects from highway construction in Montenegro, invested $660 million into the Greek port Piraeus, and purchased a 25 percent stake in the Portuguese national grid operator. Elsewhere in Europe, Italy has become the first major European power to join the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s global infrastructure project aimed at recentering world trade.

The pandemic and human rights abuses in Xinjiang, though, have shown that economic domination does not make China impervious to criticism from leaders and the citizens worldwide. “I think it’s challenging for China to wield global influence with such generally negative public views in so many countries. Just having a more prosperous economy doesn’t necessarily mean that much if you have incredibly negative evaluations,” says Kurlantzick. With slipping favorability amid human rights abuses and lingering pandemic mistrust, only time will tell if China embraces soft power more than it already has.

Does China Really Care About Soft Power?

Yao Ming

China certainly has no lack of soft power tools; it has the second most UNESCO World Heritage sites in the world at 56 total sites, trailing only Italy’s 58. Chinese athletes routinely excel at Olympic games and the country is home to world-famous athletes such as Yao Ming and Li Na. Interestingly, unlike in South Korea and Japan, Chinese media and entertainment does not seek to appeal to international audiences.

Despite this, and even with Chinese leaders stressing the need to change global opinions of the country, it is unlikely that China will embrace soft power more than it already has. China does invest in soft power, but it seems to be at a level with an imperceptible impact on perceptions tarnished by China’s handling of COVID-19 and human rights abuses. Despite the promise soft power holds, “they’re much more interested in influencing the behavior of other countries than gaining friends, particularly in Western countries. I think they’ve realized they’re never going to do well in soft power because the concept was created by Joseph Nye to argue [for] the continuing influence of liberal democracies in the world,” says Stanley Rosen, professor of political science at the University of Southern California.

“China’s highest priority remains domestic, the maintenance of political and social stability within China,” writes Rosen in his book “Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics.” This has been shown through strong crackdowns on political protests in Hong Kong and suppression of Uighurs in the western province of Xinjiang. Chinese soft power is a case of “negative soft power,” a term coined by William Callahan. The display is geared for a domestic audience and to promote legitimacy for the government — not for foreigners.

At the same time, China is not attempting to bolster its legitimacy through the promotion of shared values with other nations of the world. China has long held a “one world, many systems” perspective. Given this, Nathan Gardels, a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute, has stated the Chinese world order will be one based on the convergence of interests rather than values.

Moreover, many citizens of China also are not concerned with China’s negative relationship with the West and the United States. Citizens see the U.S. in decline and negative perceptions as “a sign of its existential angst at being overtaken by China.” It is therefore unlikely that China will shift its policy. According to Rosen, China sees the issue with Western mass media, not themselves. In a recent statement, government spokesperson Hua Chunying stated, “If the West is adamant on framing our defense of our sovereignty and core developmental interests as ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy,’ then so be it—what’s wrong with being ‘wolf warriors’ in that sense?”

“The attitude of the Chinese propaganda department is that this is a problem with western media. ‘It’s not really our fault,’” Rosen says. This cavalier attitude about negative international perception seems likely to hold, even in the face of global outrage over a number of issues. It would seem that Beijing has weighed its options and decided that economic might outweighs lingering western suspicion; time will tell if this approach proves effective.