Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get them delivered straight to your inbox!

Some of the avalanche of news this week concerning the U.S. and China has been about the news media itself. Both the U.S. and Chinese governments took action towards media organizations operating in each other’s countries.

On Feb. 18, the U.S. government notified five Chinese state media organizations that they were to be treated as foreign missions. The organizations are the Xinhua News Agency, CCTV’s international arm China Global Television Network, China Radio International, China Daily, and Hai Tian (People’s Daily’s U.S. distributor). The organizations are permitted to continue their reporting, but they would now need to:

- Identify all personnel working for their organizations in the U.S. and inform the U.S. State Department of any changes in personnel

- Identify all real estate holdings in the U.S. and inform U.S. State Department of any changes

Last fall, the U.S. State Department began requiring the Chinese staff of PRC missions in the U.S. to notify the U.S. State Department in advance if they were to meet with U.S. government officials of any level, if they were to visit public or private educational institutions or research institutions. The State Department exempted the staff of the media organizations from this requirement, but in briefing reporters, a State Department said the regulations highlight that the organizations are "not independent journalistic outlets" but are "effectively controlled by the [Chinese] government."

The Chinese Foreign Ministry decried this measure as “unjustified and unacceptable” and said it reflected the American “ideological prejudice and Cold War zero-sum game mentality.” It called for a reversal of this policy. In fall 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice ordered some Chinese state media organizations to register under the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act. CGTN registered last February.

To increase transparency, YouTube and Facebook have begun adding identifying CCTV/CGTN, Xinhua and China Daily as well as the Voice of America and Radio Free Asia as government-funded.

A couple of weeks before this change in U.S. requirements for Chinese state media, the Wall Street Journal published an opinion piece by Hudson Institute scholar Walter Russell Mead. Titled “China is the Real Sick Man of Asia,” the article was critical of how the Chinese government responded to the coronavirus outbreak, but went on to argue that “China’s financial markets are probably more dangerous in the long run than China’s wildlife markets.” Mead asked if China’s leaders could better cope with a financial shock.

China staffers and others at the WSJ knew “the Sick Man” label carried considerable historical baggage and would not be well-received in China. The fact that some Chinese reformers may have used the term themselves, for many Chinese, was irrelevant. They saw it as offensive, dating from an age when China was weak and exploited, and reflecting the views of people who could not see China or Chinese equals.

On Feb. 10, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said, “The WSJ article belittled our efforts to fight against the epidemic. Its editor also headlined the article with a racially discriminatory and sensational title… It hurts the feelings of the Chinese people and roused public anger and condemnation.” The spokesperson called for the WSJ to apologize. When no apology came, on Feb. 19 the Chinese government ordered three WSJ journal reporters to leave the country. A fourth reporter was earlier denied a visa to continue reporting from China. Observers have noted that China’s Great Firewall blocks the WSJ. None of those expelled played any role in deciding to publish the article and all produced highly respected stories over many years. Two of the expelled reporters have left. The third was reporting from Wuhan at the time of the expulsion order and cannot yet leave due to travel restrictions.

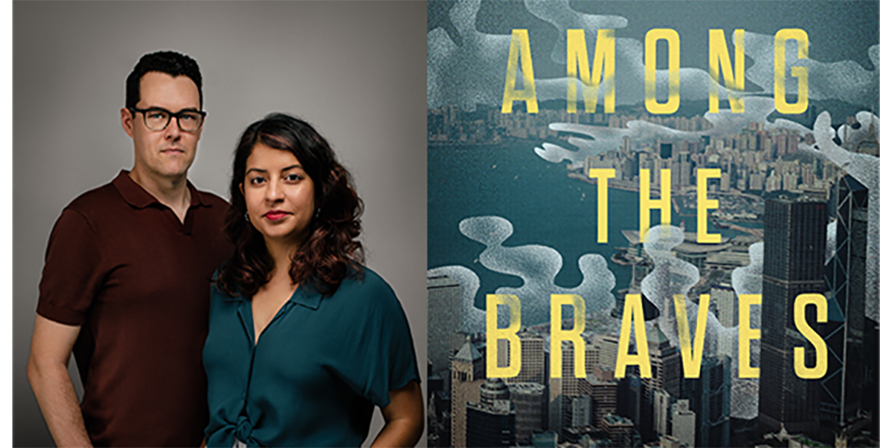

- Our Assignment: China series details the experiences of those reporting from China for American news organizations.