The article was originally published by USC News. Click here to watch the lecture.

by Cristy Lytal

Chinese authorities recently detained their country’s delegates to the Third Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, an international gathering of prominent Protestant leaders. But this action only served to underline an astonishing trend.

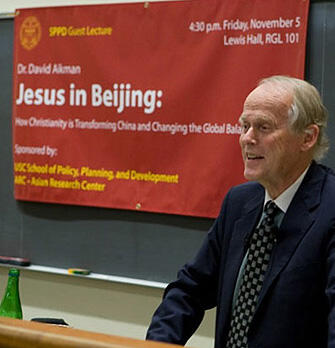

“Experts say that quite possibly, within a few years, China will be the world’s largest Christian country,” said former TIME magazine correspondent David Aikman, speaking to USC staff, faculty, alumni and students during his guest lecture “Jesus in Beijing: How Christianity Is Transforming China and Changing the Global Balance of Power.”

The USC School of Policy, Planning, and Development sponsored the event along with the USC Center on Public Diplomacy at the USC Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism, the USC East Asian Studies Center, the USC Knight Chair in Media and Religion, the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture, the USC Office of Religious Life, the USC School of International Relations, the USC U.S.-China Institute and the Asia Research Center.

"The importance of religious and cultural change in China is a huge issue for the economic and political development of the country,” said Jack H. Knott, the C. Erwin and Ione L. Piper Dean and Professor at SPPD. “The older Confucian values and more current socialist values are in interplay with Western values in creating an evolution in the relationship between individuals and the state."

Stanley Rosen, director of the USC East Asian Studies Center and professor in the Department of Political Science, added, "David Aikman's talk, in explaining the pattern of the past and the current realities, was an excellent introduction to how a conversation [about Chinese economic development, political reform and a new value system to replace the socialist ideology] might take place in the future."

Aikman began his tale with a description of Han Dynasty stone rubbings in the Hunan province depicting five loaves and two fish. "That doesn’t come from Buddhist scriptures," said Aikman, laughing. "It must have come from somebody who had knowledge of the Christian faith."

The first known missionaries in China arrived during the Tang Dynasty, when the Church of the East established congenial relations with the Chinese emperor's court.

The next major contact came when the Roman Catholic Church sent a group of Italian missionaries to meet with Mongol ruler Genghis Khan. Years later, Marco Polo delivered a letter to the pope in Rome from Genghis' grandson Kublai Khan, who requested that the church send advisers who could instruct the people of China and Mongolia in morality. The pope missed the opportunity, however, by taking a decade to respond.

In the late 1500s, Jesuit Matteo Ricci arrived in China, ushering in a new era of Sino-Christian relations.

"One of the amazing achievements of Ricci and the Jesuits was to master Chinese culture, particularly the Chinese written and spoken language, in such a way that it had a profound effect on all the scholars with whom Ricci met,” Aikman said. “Ricci could sit at a dinner table with Chinese fellow guests, listen to a Tang dynasty poem of 30 lines recited aloud in his presence and then repeat the poem perfectly word for word as though he had memorized it two hours earlier."

Johann Adam Schall von Bell and Ferdinand Verbiest, the Jesuits who headed the mission after Ricci, impressed the Chinese rulers with their abilities to predict astronomical events with more accuracy than Muslim or Chinese scholars. However, the Catholics were expelled from China in the early 1700s due to their squabbles over Chinese ancestor worship.

During the following century, several prominent Protestant missionaries arrived in China, including Robert Morrison and China Inland Mission founder Hudson Taylor.

The 1900s were not as kind to Christians in China, with the rise of nationalism and Marxism. Many Western missionaries fled, but the Christian churches were allowed a token presence in Beijing, Shanghai and other cities under an umbrella organization called the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, which was designed to supervise Protestant clergy.

From 1966 to 1976, Mao Zedong’s Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution banned all religious establishments, which ironically provided what Aikman described as “an astonishing new freedom for rural evangelists, who wandered from village to village quite clandestinely providing ministry, encouragement and support to families all over China.”

By the time that Deng Xiaoping established the new policy of openness and reform, China was poised for the rural Christian explosion that eventually reached the cities, where it influenced intellectuals, urban professions and even members of the Communist Party.

“There's no question that many in China feel that with the focus on economic development and the profound rise in materialism, that there's no longer any overarching, shared sense of mission,” said Clayton Dube, associate director of the USC U.S.-China Institute. “In this environment, Christianity has grown in popularity. It's important for students and scholars to monitor this, to understand the context of its rise, the government's response to it, and its social and political implications.”

Aikman believes these implications to be massive, given his estimate that Christians in China now number between 80 and 125 million in contrast to the four million in 1949.

“I think it’s going to have a huge impact on how China behaves, how China develops, whether China is able to make the transition from a one-party state to some form of pluralistic democracy,” Aikman said. “Whether it happens in a peaceful, orderly way depends on whether China’s Christians can persuade their fellow Chinese that the way to an orderly transformation of China is through restraint and respect and honor and peaceable-ness. And if that happens inside China, the rest of the world will have a lot to be grateful for.”

Video

Image