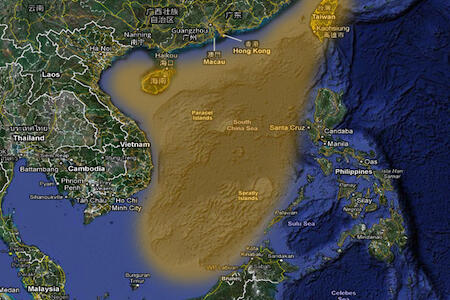

Bordered by ten nations and including some of the world’s most important shipping lanes and fisheries, the South China Sea is a vital region. Critically important mineral resources, including oil, are thought to be there in large quantities as well. The Chinese have long laid claim to nearly the entire South China Sea. That claim is contested by many nations and in some instances the conflict has turned violent. This summer the United States entered the fray.

|

| China claims most of the South China Sea. Many other governments also claim all or part of the South China Sea. |

In July, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said, "The United States has a national interest in freedom of navigation, open access to Asia's maritime commons, and respect for international law in the South China Sea.” This comment, made at a meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) regional forum held in Hanoi, triggered a vigorous response from Chinese authorities.

Chinese authorities argue that they and other nations in the region can work out their differences on a bilateral, nation to nation basis. They say that the U.S. is intruding into the discussion and attempting to make rights and use of the South China Sea an international issue. As Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi put it, “What will be the consequences to if this issue is turned into an international or multilateral one? It will only make matters worse and the resolution more difficult.”

This documentary from the USC U.S.-China Institute looks at the issue and includes interviews with distinguished Chinese and American specialists including Shen Dingli (Center for American Studies, Fudan University), Xie Tao (Beijing Foreign Studies University), Bonnie Glaser (Center for Strategic and International Studies), Daniel Lynch (USC). USCI senior fellow Mike Chinoy reports the story. USCI multimedia editor Craig Stubing handled the camerawork and editing. We look forward to your comments. Please send them to us at uschina@usc.edu.

The video is also available via our YouTube channel (http://www.youtube.com/user/uschinainstitute). The YouTube site also offers viewers the option of a higher quality video stream.

Resources:

Hillary Clinton, ASEAN Regional Forum press conference, July 23, 2010

Yang Jiechi, PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, July 26, 2010

United Nations, Oceans and Law of the Sea

PRC Foreign Ministry, Historical Evidence to Support China's Sovereignty over the Nansha Islands, 11/17/2000

U.S. Energy Information Administration, South China Sea Territorial Issues

University of British Columbia, South China Sea Informal Working Group

Transcript

MIKE CHINOY, Narrator: Could the navies of the United States and China be headed toward a show-down in the South China Sea? That’s the worse-case scenario but it’s not impossible. The reason, long-standing disputes between China and its Southeast Asia neighbors over control of the sea, have suddenly become a new source of tension between Washington and Beijing. Look at any Chinese map of the region. Almost all the waters of the South China Sea, nearly a million square miles and believed to contain vast underwater deposits of oil and natural gas, are marked as China’s maritime territory. According to Beijing, it’s a claim rooted in Chinese history.

SHEN DINGLI, Fudan University, Shanghai: For China, we say our ancestors used to occupy these islands. So I have this book to show. Look, and my fishermen used to use islands to avoid the typhoons. It’s all recorded. And there are so many vessels unearthed that carry Chinese porcelain. It’s not Vietnam’s porcelain. So we consider that a thousand years ago, these people already used this sea lane of communication for China’s interests. Therefore, the ancestors of them have the right to claim.

Mike Chinoy: But the South China Sea is also bordered by Vietnam, Taiwan, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, and most of them have their own territorial claims and for similar reasons. Not only the potentially rich natural resources, but the fact that a third of the world’s trade and much of Asia’s oil, pass through its sea lanes.

XIE TAO, Beijing Foreign Studies University: That area, why is China claiming sovereignty and some other countries are competing for sovereignty is because of the energy supply, potential energy supply.

MIKE CHINOY: Over the years, these rival claims have led to numerous clashes between China and Vietnam, China and the Philippines, Taiwan and the Vietnam, Vietnam and the Philippines, the Philippines and Malaysia. Despite its large naval presence in the Western Pacific, the United States has never taken sides in these disputes. Indeed, the South China Sea has been low on Washington’s list of Asian concerns.

But all that changed in July. Although still officially not taking sides, at an Asian regional forum in Vietnam, Secretary of State Hilary Clinton declared that the U.S. had a “national interest” in maintaining freedom of navigation in the area, in seeing disputes resolved in a “collaborative diplomatic process without coercion”, and Washington was opposed to “the use or threat of force by any party”.

DAN LYNCH, University of Southern California: What’s really astonishing about it, the statement itself sounds benign. It just sounds like a personal reasonable, responsible position that any state could take. What that implies is that the United States contests and will potentially seek to block China’s claim-the realization of China’s claim over the South China Seas. If you read between the lines, it was a sharp rebuke to China’s position and I’m sure that’s how it was read in Beijing.

MIKE CHINOY: China’s reaction was swift and angry.

CCTV ANCHOR: A defense ministry official says China has indisputable sovereignty over islands in the South China Sea and the surrounding waters.

SENIOR COLONEL GENG YANSHENG: We oppose the internationalization of the South China Sea issue.

MIKE CHINOY: An editorial in the Global Times, published by the communist party mouthpiece People’s Daily, was even tougher, warning that quote China will never waive its right to protect its core interest with military means.

Indeed, it was China’s use of the term “core interest” to describe the South China Sea that was a key factor in Washington’s new, tougher approach.

DAN LYNCH: In the spring, Chinese officials in conversations with American officials announced that the South China Sea was now a core interest of China along the lines of Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang, completely unnegotiable claim to sovereignty. China’s long-time claimed the South China Sea, but they had never elevated it before to a core national interest. You know you think of core national interest usually implies this is something we will fight for.

MIKE CHINOY: These comments followed what the U.S. saw as increasingly muscular moves in the South China Sea. These included China’s detention of Vietnamese fishermen in the disputed waters, warnings to U.S. oil companies not to engage in joint South China Sea exploration deals with other nations, and a Sino-American naval confrontation in the spring of 2009. Chinese vessels coming within just a few yards of the US navy surveillance ship, the Impeccable.

Beijing’s justification for harassing the Impeccable was that-in addition to sovereignty over most of the South China Sea, China has a 200 mile exclusive economic zone that extends from any land feature bordering the sea.

BONNIE GLASER, Center For Strategic and International Studies: There is a dispute about what kind of activities countries can have in their exclusive economic zone. From the Chinese point of view, military activities that are harmful to the country that claims that EEZ should not be allowed. From the U.S. point of view, the activities that can be conducted in an EEZ include military activities.

SHEN DINGLI: China’s argument is that U.S. Pentagon ships, even unarmed ships, even a military surveyor, inside the Chinese EEZ constitute not innocence, constitute a harm because it’s military. Why you make such a mapping of the sea bed in my economic zone. So China considers it I have a right to deny.

MIKE CHINOY: Beijing’s assertiveness was coupled with intense pressure on Southeast Asian nations to negotiate their differences with China bilaterally…where, of course, China, given its size and clout, would have a significant advantage.

XIE TAO: The assumption is that because you are so big, and the other side is so small, if you do bilateral, that means you are engaging unfair negotiations. So I think the South China Sea is becoming a sensitive spot today precisely because so many countries there are getting very uneasy about China’s presence.

MIKE CHINOY: China’s new attitude was coupled with a growing sense in Beijing of Chinese strength-and deepening American weakness.

SHEN DINGLI: When we grow more strong, why we have to be more subordinate, obedient to America. For China, we are getting more power, yes. We can more assert our rights.

BONNIE GLASER: In the aftermath of the financial crisis, there were some judgments in Beijing that the United States was weakened, distracted by Iraq and Afghanistan, and that this gave China more running room. China emerged from the financial crisis relatively unscathed and I do think there were some people in China who saw this as an opportunity to try to exert China’s influence and perhaps further, even weaken, U.S. influence in the region.

MIKE CHINOY: Under the circumstances, Vietnam and several other members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations-ASEAN-urged the Obama Administration to adopt a tougher line…something Washington was ready to do precisely to counter the impression of weakness.

BONNIE GLASER: The Obama administration, I think, realized that China had drawn this conclusion and was worried about the potential for miscalculation as a result of this judgment. And therefore, I do think that there has been a concerted judgment and decision in Washington to ensure that China understands that we are present in the Asia-Pacific region, we are not weaker, we are not distracted.

MIKE CHINOY: Indeed, Secretary of State Clinton’s declaration in Hanoi also coincided with joint U.S.-South Korean military exercises off the Korean Coast. Although aimed at deterring North Korea, an angry Beijing saw them as yet another example of American muscle-flexing in waters so close to China.

QIN GANG, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman: We firmly oppose any foreign warships and airplanes to conduct activities undermining China’s security interests in the Yellow Sea and any other close Chinese waters.

MIKE CHINOY: Taken together, the U.S. moves fueled a sense among many Chinese that Washington is trying to block China’s rise.

XIE TAO: I think this is a widespread concern. I think if you interview some of these military top brash that they would lambaste the United States for another imperialistic design against China. You know, they are trying to encircle China. They are trying to suffocate China. It’s strategic space.

DAN LYNCH: The United States is trying to shape China’s rise. It’s certainly trying to shape and constrain China’s rise so that it rises into one kind of power not another and especially a power I think that continues to respect and acknowledge American supremacy, American leadership, globally. That’s what it looks like the United States wants from a rising China and that’s what it looks like Chinese elites now at least want to contest.

MIKE CHINOY: In both Washington and Beijing, domestic politics limit the ability of either government to back down. President Obama can’t risk being accused of being “soft” on China. His Chinese counterparts have the same problem.

XIE TAO, Beijing Foreign Studies University: This has been a position of the Chinese government since 1949. So say, in the time of Chairman Mao, the central government says “We claim sovereignty over these islands.” And today, any leadership, if you come in and say “I think we probably need to give away that kind of sovereignty,” no leadership can do this.

BONNIE GLASER: This is a very complex relationship that needs to be managed very carefully on both sides. I think it’s important for both of our countries, the United States and China, to be very realistic and understand that we do have areas of interest that clash.

MIKE CHINOY: To a worryingly long list of divergent interests troubling US-China relations therefore-a new one can now be added-how to handle a potentially volatile conflict over the South China sea. I’m Mike Chinoy.