Andrew Plaks is Professor of East Asian Studies at Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He was Professor of East Asian Studies and Comparative Literature at Princeton University until his retirement in 2007. He is an internationally recognized authority on Classical Chinese literature. His major works include Archetype and Allegory in the Dream of the Red Chamber, The Four Masterworks of the Ming Novel (winner of 1989 Joseph Levenson Book Prize), The Highest Order of Cultivation and On the Practice of the Mean, etc.

As in the Biblical Song of Songs, the "enclosed garden" of the Daguanyuan in Honglou meng serves as a symbolic construct signifying a self-contained world of virginal purity and innocence. But in the course of the novel the walls of this inviolable space are breached in a number of ways: both from within, through the psycho-social dynamics of human interaction, and from without, by the forces of power and corruption of the "real" world outside its gates. Together with its primary literary model Jin Ping Mei, Honglou meng presents an essentially imaginary world that occasionally provides a surprisingly accurate reflection of certain details of the social and economic history of, respectively, the Wan-li and Qianlong periods. In the latter case, this has much to do with the largely autobiographical, confessional impulse informing the composition of the fictional text, but it is also grounded in the novel's basic mimetic stance of verisimilitude, within which even the more anti-realistic aspects of the narrative are anchored in a recognizable frame of contemporary reality.

In this talk, I will focus on two aspects of the fictionalized reality reflected in the pages of Honglou meng. First, I will address the direct and indirect presentation of the social status of the Jia family, both as embodied in specific circumstances of the narrative, and as expressed in the words of the characters themselves. In reconsidering the special elite position of the masters of the private realm within which the story unfolds, I will pay special attention to the degree to which the fading recollections of the forefathers who first acquired wealth and prestige through military exploits, and the extraordinary access of their descendants within our story to the Throne and to the extended Imperial family, correspond to the picture of bannermen/bond-servant connections associated with the forebears of Cao Xueqin. I will also look at the internal hierarchies within the Jia compound itself, with respect to the blurring and crossing of lines between servants of varying levels of seniority and competence, between members of the urban and rural branches of the extended clan, and between lower-ranking relatives of the family vis-à-vis the higher-ranking servants, as well as the avenues of social line-crossing afforded by the various modes of secondary marriage and concubinage we observe in the text.

Secondly, I would like to take a more careful look at the legal status, and particularly the privileges and prerogatives, conferred by the hereditary titles and nominal ranks, as well as the actual government service, of the central male characters. This is of special relevance to those places in the story that depict milder application of the legal codes, commutation of penalties, or even immunity from prosecution in certain cases, as opposed to the waiving of such privileges in cases of impeachment for gross malpractice in government service, or the more severe application of penal strictures in instances of egregious or potentially subversive criminal behavior, with special attention to the crime of possessing luxury goods reserved for Imperial use.

Leaving the technical analysis of these questions to scholars of Qing legal and social history, I hope that the bits of information about these matters to be gleaned from Honglou meng may help to sharpen our understanding of the broader historical significance of broader issues of self-identity and group affiliation in late-Imperial China.

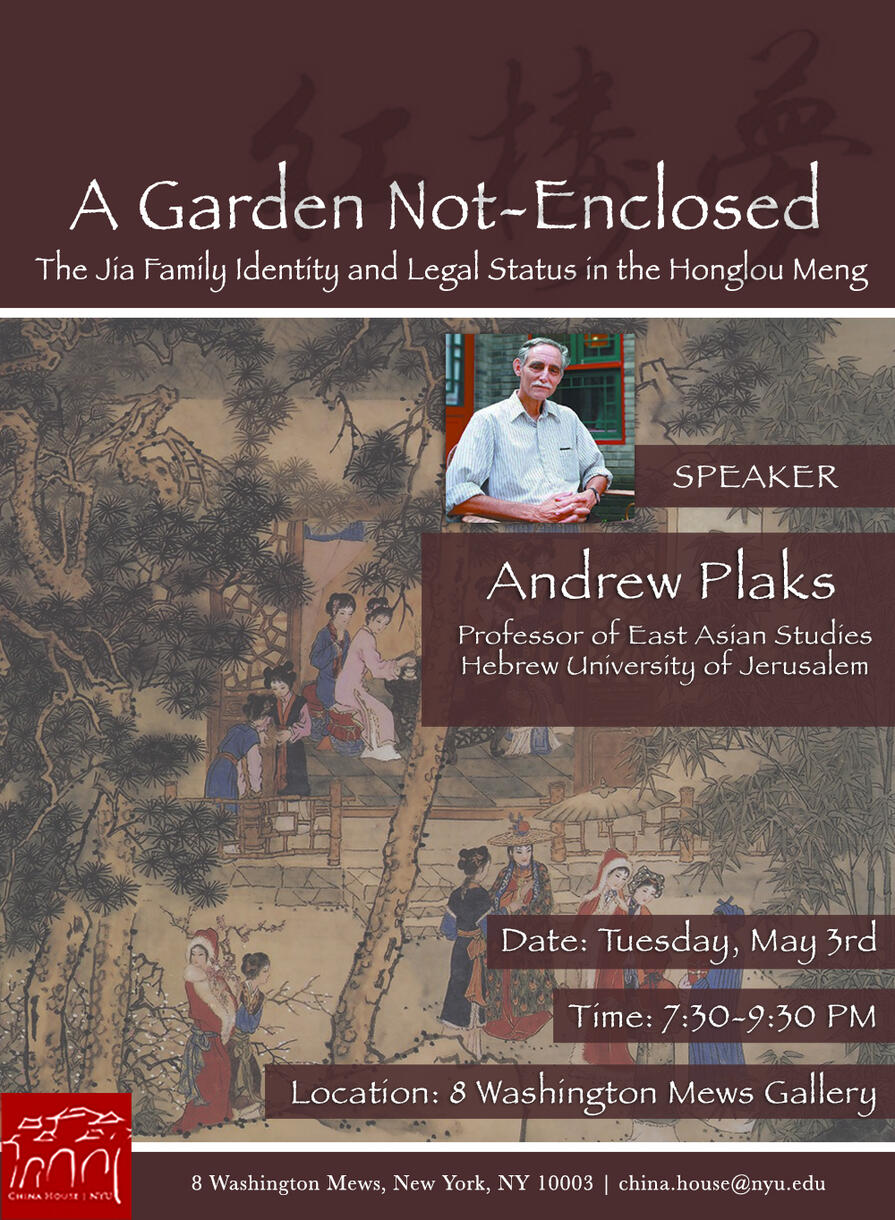

Image