By Sasha Tsui

Catastrophe can bring out the best or the worst in people. A murderer might save a child from danger. An ordinarily good and generous person might act selfishly under stress. This is also true in public diplomacy. During a disaster, a traditional rival could be a genuine friend by offering timely help while a customary friend could diminish its reputation by failing to offer much help. In the eyes of many Chinese, this has happened due to how Japan and the United States responded to the novel coronavirus outbreak.

|

|

| Japanese embassy post, netizen comments |

|

|

| US embassy post, netizen comments |

Since the outbreak, Japan has sent a number of charter flights carrying relief goods to Wuhan, the epicenter of the crisis. The shipments include supplies provided by the Tokyo metropolitan government and Wuhan’s sister city Oita. Instead of celebrating the 40th anniversary of the sister-city relationship on March 8, Oita’s government donated 30,000 face masks. The official message is clear: Japan is there to help.

Japan has a clever strategy. Commit to aid diplomacy and publicize the aid. By Feb. 6, the Japanese government had offered 11 posts about the virus and what it was doing via its official Weibo account (Chinese Twitter). Seven of them included the hash-tag “Hang on! Wuhan” (Wuhan jiayou 武汉加油). Three are detailed lists of donations from 60 city governments, mentioning approximately 130,000 masks, 23,000 pieces of protective clothing, 33,000 pairs of goggles, 50,000 pairs of gloves and 3,000 sterilization-related supplies.

These actions are seen by Chinese as Japan demonstrating awareness of and sympathy toward China. Chinese see this as the behavior of a good neighbor. Within China, the online discussion has mainly about a new understanding of the Japanese government and the appreciation of the Japanese people. Surprisingly, more than one blogger offered to temporarily restrict the entry of Chinese citizens to ensure that the 2020 Tokyo Olympics can go forward. In fact, Japan’s aid diplomacy is helping both sides soften their hard positions and warm frosty relations. Similarly, its respectful treatment of corpses at the time of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake won Japan much praise in Chinese social media.

While Japan is seen as a rival burying the hatchet, the United States is losing the hearts of Chinese netizens. This may be a slight exaggeration, but is definitely evident. Weibo news feeds emphasize the U.S. evacuation of 195 U.S. nationals, U.S. airlines suspending flights to China and denying entry to non-citizens who recently traveled to China. Netizens are disappointed. Several other countries also airlifted citizens out of China and imposed travel restrictions. Why, then, does United States alone draw much of the dissatisfaction? The main reason is the United States has been at the center of Chinese attention for decades. Chinese expect the U.S. to come to their aid, especially when other nations line up to notify their donation of face masks and test kits along with those safety measures, such as the United Kingdom, France and South Korea.

The U.S. government also has a Weibo account. By Feb. 2, there were 37 posts about the virus, 27 of which were travel alerts and three were safety tips. None of the posts mentioned the scientific collaboration between Chinese scientists and American researchers for vaccine development or the planned aid from Pittsburgh, another sister city of Wuhan. Silent aid diplomacy is not effective.

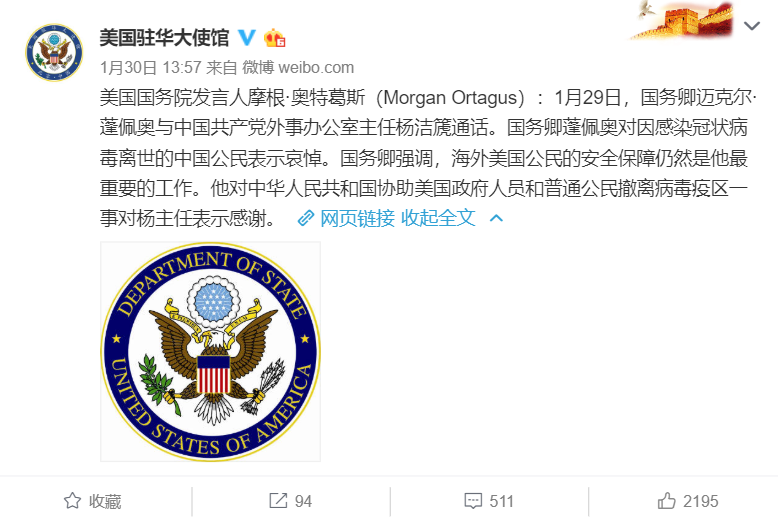

One of the remaining seven posts directly articulated the priority of the U.S. government. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo emphasized that the security of U.S. citizens overseas was his principal concern and he expressed appreciation for China’s assistance in evacuating U.S. citizens. The official message to Chinese people is shocking: the United States only cares about Americans and despite its suffering, China is there to help U.S. citizens flee.

This is a bad move and disappoints Chinese. Because during a crisis, people are more sensitive about such actions. People tend to draw a sharper line between those who prove to be friends when you are in need and those who do not. Such judgments generally follow official statements and actions rather than the work of companies, organizations or individuals. In this case, Chinese people had not expected Japan to be so warm-hearted, so the goodwill and generosity made a deep and positive impression. In contrast, Chinese expect more of the United States and they feel the U.S.government fell short. Actions and words both were inadequate. This has brought a great psychological letdown.

On February 3, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying commented, “the US government has not provided any substantial help to China” during an online press conference. In the following three days, US government’s Weibo account has posted eight threads, one of which quoted U.S. Department of State spokesperson Morgan Ortagus, “the US Department of State is working with US companies and charitable organizations to assist the delivery of donated medical supplies to teams working on the novel coronavirus in China. Flights to bring people out carry critical supplies.” Online public opinion towards US may improve, especially as details of the help are shared as Japan has done.

Social media is more open in China than traditional media. Twitter-like Weibo is a nice channel to observe Chinese perceptions of international responses to the coronavirus outbreak. Generally, Chinese feel Japan’s response to the coronavirus outbreak is better than America’s, especially when US aid efforts and Japanese worries in Japan were not widely known.

It is worth noting that reception of Chinese abroad is different from support for suffering or threatened Chinese within China. The former does however reveal much bias and the darker aspects of international attitudes. Many Chinese are also aware that those attitudes includes questions regarding the need for the lunar new year mass migration and the necessity of wearing a mask every day, criticism of Chinese eating habits, raising bio-weapon conspiracy theories and even worse, spreading anti-China fear and racism sentiments.

Sasha Tsui is a doctoral student at Renmin University in Beijing. She is currently studying public diplomacy at USC.