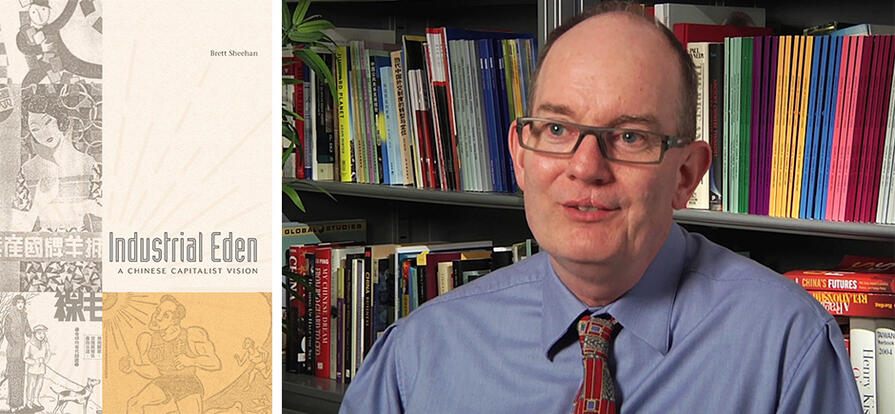

About the book:

Industrial Eden: A Chinese Capitalist Vision is an illuminating study of the evolution of Chinese capitalism chronicles the fortunes of the Song family of North China under five successive authoritarian governments. Headed initially by Song Chuandian, who became rich by exporting hairnets to Europe and America in the early twentieth century, the family built a thriving business against long odds of rural poverty and political chaos.

A savvy political operator, Song Chuandian prospered and kept local warlords at bay, but his career ended badly when he fell afoul of the new Nationalist government. His son Song Feiqing—inspired by the reformist currents of the May Fourth Movement—developed a utopian capitalist vision that industry would redeem China from foreign imperialism and cultural backwardness. He founded the Dongya Corporation in 1932 to manufacture wool knitting yarn and for two decades steered the company through a constantly changing political landscape—the Nationalists, then Japanese occupiers, then the Nationalists again, and finally Chinese Communists. Increasingly hostile governments, combined with inflation, foreign competition, and a restless labor force, thwarted his ambition to create an “Industrial Eden.”

Brett Sheehan shows how the Song family engaged in eclectic business practices that bore the imprint of both foreign and traditional Chinese influences. Businesspeople came to expect much from increasingly intrusive states, but the position of private capitalists remained tenuous no matter which government was in control. Although private business in China was closely linked to the state, it was neither a handmaiden to authoritarianism nor a natural ally of democracy.

This video is also available on the USCI YouTube Channel.

About the author:

Brett Sheehan is professor of Chinese history at the University of Southern California. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California-Berkeley in 1997. He is also the author of Trust in Troubled Times: Money, Banking and State-Society Relations in Republican Tianjin, 1916-1937 (Harvard University Press, 2003) and numerous articles and book chapters.

Reviews:

“Industrial Eden is a fascinating and important study of modern Chinese capitalism that tracks the long arc of a business family from its rise in the late-nineteenth century to the collapse of its fortunes in the 1950s. The documentary basis of the book is rich and exhaustive; no archival stone has been left unturned. The book offers a rare and revealing picture of political and economic change taking place in tandem, in alternating moments of rise and ruin.”—David Strand, Dickinson College

“Sheehan deftly handles a complex subject—the changing fortunes of one family’s enterprise through five political regimes spanning more than a century. Industrial Eden is a valuable addition to the literature on business–state relations in twentieth-century China and will remain important decades to come.”—Karl Gerth, University of California, San Diego