Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

Talking Points, February 8-20, 2013 Happy Year of the Snake!

|

Talking Points February 8 - 20, 2013 skip to the stamps | skip to the calendar Updated in 2022, originally published Feb. 8, 2013 Happy New Year! 祝您蛇年快乐! Every lunar new year we gather stamps issued in China, the United States, and by many other countries and regions to mark the occasion. On February 10 this year, we usher in the Year of the Snake 蛇年. Last year, several governments issued lunar new year stamps for the first time. This year, Gibraltar joins the mix. Relative newcomer Liechtenstein utilizes a traditional papercut design.Here we share stamps from the U.S. and China. Our complete collection of stamps from more than thirty governments is at the end of the newsletter.

Deng Xiaoping and his supporters were maneuvering to restore him to power. He challenged Hua’s assertion that Mao’s policies and directives were sacrosanct. In a letter to central party officials Deng insisted “There has never been a person whose statements are always correct or who is always absolutely right.” A central obstacle to Deng’s return was Mao’s verdict on the April 1976 demonstrations in Tiananmen Square. Interspersed with mourning for Zhou Enlai, the late premier, were poems criticizing other leaders. Those demonstrations were suppressed by the authorities and subsequently labeled counterrevolutionary. Mao and his circle blamed Deng for the unrest. In early 1977 Party elders presented evidence to Hua and others refuting this and Hua stopped public criticism of Deng. By summer, Deng was back in his old posts and by December 1978 he was fully in charge, initiating economic reforms and opening the country to foreign technology and investment.

Two other big shifts from that year of the snake continue to affect China today. The first was a renewed emphasis on developing China’s scientific capabilities. This would come through rebuilding higher education, including a return to competitive entrance exams and sending researchers and students abroad. In 1977, 5.7 million took the exam, with just 272,971 earning admission. Now, about three-fourths of the 9 million who take the exam are admitted. In fall 1978, a few hundred students went abroad, including four dozen to the United States. Three of those students came to USC. Today, more than 194,000 students from China are enrolled at U.S. universities, including more than 2,500 at USC. Deng was instrumental in this push to reinvigorate Chinese human capital. Renewed state attention to population growth was another 1977 development with long-reaching implications. The government publicized statements Mao made in 1957 supporting efforts to stem population growth. This was significant because Mao subsequently condemned the work of those who wanted state action to limit growth, arguing that growth was a

sign of socialism’s success in building China. Also in 1977, a book on population theory was published (the sensitivity of the subject caused its authors to initially withhold their names). Over the next couple of years, scientists weighed in and the discussion was increasingly framed in national security terms . By 1980, the one child limit was mandatory for nearly all families. Much of the drive to establish firm birth limits and rigorously enforce them (as opposed to the reliance on exhortations to delay marriage, extend the interval between births, and have fewer children: the wanxishao 晚 稀 少 slogan) stemmed from the 1960s baby boom. From 1962 to 1970, the crude birth rate was as high as 43/1,000 a year and never below 33/1,000 a year). Officials, though, were reacting to a trend that had already changed. By 1977, the crude birth rate had steadily dropped by more than a third to 19/1,000. The draconian enforcement measures and social responses that ensued and came at great political and human cost were probably not necessary. Of course, planners in 1977 had little sense of the enormous changes that would come in Chinese society. They couldn’t have known that the economic development, urbanization, and higher levels of education for women that was in China’s future would “naturally” yield smaller families.

By this time, Fang was a well-known dissident. His writings and speeches helped inspire students to demonstrate in Beijing in 1986. As a result, he was stripped of his academic leadership position and was expelled from the Chinese Communist Party. But he was permitted to continue with his research and writing. The essay cited above was not Fang’s first provocative act of 1989. In January, he’d written a letter to Deng Xiaoping, later shared with reporters, calling for the release of political prisoners, including Wei Jingsheng who had been jailed in 1979 for arguing China needed a fifth modernization, democracy, in addition to Deng’s list of four.

Fang entered the international spotlight just a couple weeks later when he was invited to attend a banquet hosted by George H.W. Bush, who was making his first trip to China as U.S. president. Fang’s car was stopped by police and he was prevented from reaching the dinner. The White House publicly expressed regret over the police action, but privately sent signals blaming the incident on the embassy and suggesting to Chinese officials that Bush intended no offense. There were plenty of smiles when Bush met Deng and when he and his wife received Flying Pigeon bicycles from Premier Li Peng, a gift intended as a remembrance of how the Bush family sometimes bicycled around Beijing when he headed the U.S. Liaison Office there in the mid-1970s. By April 1989, it was clear that Fang’s prediction that at least some Chinese would be in a reflective mood was correct. On April 15, students seized upon the death of Hu Yaobang, the former CCP general secretary removed by Deng Xiaoping over his handling of the 1986 student protests. Students went to Tiananmen Square, as others had done in 1976, and in mourning Hu also criticized other leaders and the authoritarian government. The protests grew in Beijing and spread to other cities. The party leadership was divided in how to respond. People’s Daily labeled the protests as counterrevolutionary and martial law was declared. Ultimately the party state used soldiers and guns to end the demonstrations. Deng Xiaoping and his fellow elders removed Zhao Ziyang as CCP general secretary, congratulated the army on restoring order, and weathered the international condemnation that followed the bloodshed and rounding up of protest leaders. Economic sanctions imposed by the U.S. and others stung, but China’s post June 4 economic problems were even more a function of a credit contraction ordered in 1988 to stem inflation. In fact, resentment over inflation and official corruption had done much to bring workers and others into the streets to support the student-initiated protests. Economic reform and engagement with the larger world continued, though it was not steady and sometimes required bold leadership. Exports were expanding, foreign investment increasing, and cities were growing as migrants from the countryside found factory, construction, and service work. American television shows as varied as cop dramas (e.g., Hunter), soap operas (e.g., Dynasty), and historical miniseries (e.g., Roots) were among the foreign fare that many Chinese had been consuming on state television networks since the 1980s. On pirated VCDs and, later, DVDs they watched a whole lot more. By the next snake year, 2001, China had quadrupled college seats compared to the early 1980s and more students were finding opportunities to study abroad. Perhaps the most significant event of snake year 2001, for China and the world, was its December entry into the World Trade Organization. Premier Zhu Rongji had used this objective to help him push through reform of many of China’s moribund state-owned enterprises. Some went bankrupt and others forced workers into early retirement in order to improve their balance sheets. Many major enterprises were pushed to adopt at least the appearance of adhering to international norms of accounting so as to get access to capital through listing on exchanges in New York and elsewhere. Getting China into the WTO wasn’t just an objective of the Chinese leadership. Many American leaders, including President Bill Clinton wanted it and pushed hard to make it happen. In asking Congress to grant China permanent normal trade relations status, Clinton argued, “[I]f you believe in a future of greater openness and freedom for the people of China, you ought to be for this agreement. If you believe in a future of greater prosperity for the American people, you certainly should be for this agreement. If you believe in a future of peace and security for Asia and the world, you should be for this agreement. This is the right thing to do. It's an historic opportunity and a profound American responsibility.” Many things have happened in the eleven years since China entered the WTO and became more involved with other international organizations. First, China has become one of the world’s top trading nations (no. 1 in exports, no. 2 in imports and in the top four in services). China has become the second most popular destination for foreign direct investment. Trade and investment have helped China build the world’s second largest economy. This progress is evident in the skylines of cities and in the much improved living circumstances of hundreds of millions of people. China’s gross domestic product per capita has increased fivefold since the country entered the WTO. In 1977, the U.S. and China exchanged $372 million in goods. Last year, the two countries exchanged more than $500 billion in goods. Since entering WTO, China's exports to the U.S. have increased fourfold. What most Americans don't realize is that U.S. exports to China have increased fivefold since 2001. In snake year 2013 Chinese enjoy much more freedom in the personal lives than they did in 1977 or even 2001. The communications revolution and greater openness and opportunity for travel have expanded Chinese horizons and widened contacts immensely. At the same time, many political constraints remain and simple speech can be labeled a threat to the state and punished severely. Some are limited in their ability to peacefully practice their religion. Non-state sponsored organizations exist, but are vulnerable to arbitrary state action. The party-state remains jealous of its authority. The tendency to argue foreign hands must be behind organized expressions of discontent remains strong. As China enters this year of the snake, it faces enormous challenges. In surveys, the Chinese public readily identifies many of these: horrific pollution, a widening gap between rich and poor, and pervasive official corruption tend to top the list, but people also complain about the prices of health care, housing and food prices. China’s increasingly better educated population has trouble finding satisfying work. Real improvements in living standards haven’t kept up with rising expectations of those saturated in advertising, soap operas, and the conspicuous consumption of their social media networks. The rapidly aging population and the skewed sex ratio of the under-30 population pose social and economic problems. The Chinese government no longer releases information on civil disturbances, but most believe strikes, marches, and other protests, some of them violent, have increased in number in recent years.

On the international horizon, China is engaged in several territorial disputes that threaten to flare up into serious conflicts. Multinational firms complain that they remain shut out of key Chinese markets and that the Chinese state unfairly aids its firms in moving into foreign markets. Some foreign firms are moving production out of China to save money, protect their intellectual property, or to get closer to vital markets. This is a fairly daunting list of real and potential problems. At the same time, in snake year 2013 China has much greater resources to address some of these challenges. China is much more involved in international organizations (e.g., in 2012 China contributed more personnel to United Nations peacekeeping operations than the other four permanent members of the Security Council combined). Ties with countries such as the U.S. are multifaceted and those involved have found ways to effectively collaborate. So much has changed for China, the U.S., and the world since snake year 1977. We are far more interdependent than we were then, which makes effective leadership and sustained cooperation all the more essential if we are to seize opportunities and cope with complex and pressing issues. Here’s hoping we all have an outstanding year of the snake! Year of the Snake Stamps China

1989 and 2001 Hong Kong 2001 Macau Taiwan (Republic of China) United States (and 2001 version)

Australia Cambodia (2001)

Canada Gambia (2001) Guyana (and also 2001 version) Indonesia

Isle of Man Japan Korea, North Korea, South Liechtenstein

Mali (combination Dragon/Serpent stamp sheet) Micronesia (2001)

Mongolia

New Zealand Palau (2001)

Papua New Guinea Philippines Serbia

Singapore Slovenia Somalia (2001) Thailand United Nations Most countries use the term "lunar new year," recognizing that several East Asian nations have utilized the calendar and celebrate the new year. The UN, however, prints its stamps on a sheet that says, "Chinese Lunar Calendar." Vietnam Some countries have opted to issue sets of twelve stamps to cover the full lunar cycle. Snake samples from those collections are below. Antigua & Barbuda Grenada Liberia Sierra Leone

Want more lunar new year stamps? |

|

*****

Below and at the calendar section of our website we offer information about China-focused programs and exhibitions across North America. The resource section of our website offers information about available fellowships, our online collection of speeches, treaties, and reports, and more. We always appreciate your feedback grateful when you pass Talking Points on to friends, students, and colleagues. They can write to us at uschina@usc.edu to join our mailing list. Click here to see back issues of Talking Points.

We welcome and need your financial support. Donations in any amount are welcome and are tax deductible in the U.S. Click here to donate via the secure USC server. Thank you for reading. We look forward to hearing from you. Best wishes,

Subscribe at http://china.usc.edu/subscribe.aspx

USC | California | North America | Exhibitions

Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism, ASC 204

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089

Time: 4:00-5:30PM

Cost: Free, RSVP at uschina@usc.edu.

The USC U.S.-China Institute presents a talk by Ryan Pyle, longtime China-based photojournalist, showcasing photographs and video from his most recent 18,000 km journey across China.

Omni Hotel

Below are exhibitions ending in the next two weeks. Please visit the main exhibitions calendar for a complete list of ongoing exhibitions.

USC U.S.-China Institute | 3535 S. Figueroa Street, FIG 202 | Los Angeles | CA | 90089

Tel: 213-821-4382 | Fax: 213-821-2382 | uschina@usc.edu | china.usc.edu

|

Featured Articles

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

Events

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?

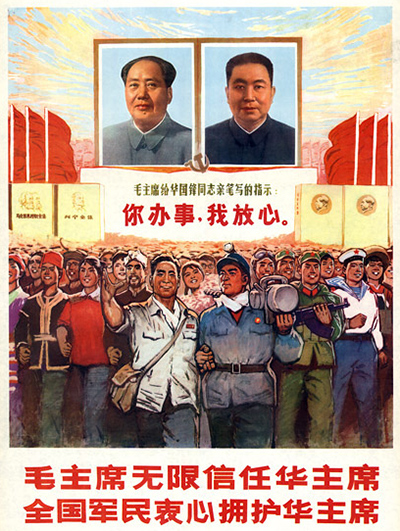

Looking back at previous snake years gives us a chance to quickly see how much has changed in China and in the U.S.-China relationship. In 1977, Chairman Mao Zedong’s widow and some of her political allies hadn’t yet marked six months in jail. Hua Guofeng was chairman of the party, premier, and chair of the party’s central military commission. In a prominent editorial just before the lunar new year, the People’s Daily reiterated the “two whatevers” 两个凡是 approach Hua had articulated in October: “We firmly uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and we unswervingly adhere to whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave.”

Looking back at previous snake years gives us a chance to quickly see how much has changed in China and in the U.S.-China relationship. In 1977, Chairman Mao Zedong’s widow and some of her political allies hadn’t yet marked six months in jail. Hua Guofeng was chairman of the party, premier, and chair of the party’s central military commission. In a prominent editorial just before the lunar new year, the People’s Daily reiterated the “two whatevers” 两个凡是 approach Hua had articulated in October: “We firmly uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and we unswervingly adhere to whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave.”

02/13/2013: Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, Something - Red? China's Performing Arts in the 21st Century: a marriage of tradition and modernity, east and west

02/13/2013: Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, Something - Red? China's Performing Arts in the 21st Century: a marriage of tradition and modernity, east and west

02/21/2013: Images from the Four Corners of China

02/21/2013: Images from the Four Corners of China