Iowa and China | US ambassadors to China | Calendar

Unpredictability is the new watchword in U.S.-China relations. Whether it is maneuvering in the South China Sea, direct talks between Taiwan’s president and America’s, China’s imposition of tighter foreign exchange controls or the U.S. blocking of the sale of a German firm to China, the past two weeks have offered much to think and talk about.

For ten years now, the USC U.S.-China Institute has helped inform public discussion of what’s important in the U.S.-China relationship and what is changing. We’ve done this through our conferences and

|

public talks, through our documentaries and web magazines, through the faculty and student research we’ve sponsored, and through professional development programs for teachers and others. We’ve done this through our web calendar and Talking Points newsletter. Where else can you find a comprehensive continent-wide listing of events and exhibitions relating to China? Journalists and others routinely draw on the research of institute-affiliated experts or look to them for informed commentary.

All of these efforts take money. We need your help if we are to continue. So please consider supporting the institute with a tax deductible contribution. Gifts of any size are both needed and appreciated. It is quick and easy to donate via the secure USC server, via check, or via wire transfer: SUPPORT USCI.

Please act now if you believe that timely, reliable, and research-driven information about today’s China and about the U.S.-China relationship is essential. A new U.S. president will soon assume office and in fall 2017, China’s Communist Party will assemble to determine who will lead China for the next five years. Major economic, security, and other policies are in flux. Please support the USC U.S.-China Institute so that we can continue to foster a fuller, deeper, and more nuanced understanding of the 21st century’s most crucial relationship.

*****

In our next issue, Talking Points examines myths and realities of U.S.-China trade. Now, though, we note President-elect Donald Trump’s choice of Iowa Governor Terry Branstad to be the next U.S. ambassador to China.

Governor Branstad’s nomination got a lot of attention because it is an important post and because it preceded Trump’s choice of Exxon chief Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State. Much of the press attention on Branstad focused on the fact that he briefly met Xi Jinping when he was a member of a delegation that visited Iowa in 1985. A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman greeted rumors of the choice with the observation that “Branstad is an old friend of China.”

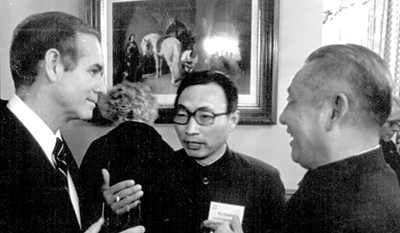

1980: Iowa Gov. Robert Ray and Guangdong Gov. Xi Zhongxun (right). No Western suits among Chinese visitors. (Des Moines Register photo) |

1985: Hebei delegation, including Xi Jinping (third from left), visits Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad (center) |

Hebei delegation relaxing with Muscatine, Iowa hosts. |

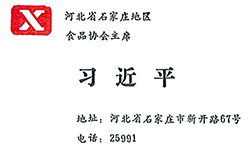

Xi Jinping's business card. No postal code, internationally-accessible phone number, email address, and definitely no WeChat QR code. |

Branstad and his predecessor Robert Ray started pursuing Chinese trade not long after the U.S. and China established formal diplomatic relations. Ray visited China in 1979 and 1980 and hosted a visit that included Xi Jinping’s father Xi Zhongxun in 1980. When Branstad moved from lieutenant governor in 1983 to the top job, he agreed to make Hebei Province Iowa’s official Sister State. In 1984, Branstad took forty-five Iowans with him on a trade mission to Hebei and in 1985, the province sent a handful of officials, including Xi Jinping, to Iowa. In part to save money, the Iowa Sister State committee put the visitors up in the homes of cooperative citizens. The visitors loved this, the barbeques, and more. Xi Jinping was party secretary of Zhengding County 正定县. His business card, now on display in a museum commemorating the visit identifies him as chair of the regional food products association.

In 2007, Xi was elevated to the Communist Party Politburo Standing Committee and in 2008 he was made vice president. Iowa opened a trade office in Beijing in 2008. Branstad had opened one in Hong Kong in 1985. In 2011, Branstad (again governor after a few years as a university president) met with Xi in Beijing and invited him to return to Iowa. Xi Jinping took him up on the offer in 2012, revisiting his Muscatine host family as well as the Kimberley family farm. He told the Kimberleys that he wants to replicate the farm in China. He was impressed by the use of technology, including grid sampling of soils, using GPS for planting and harvests, and hybrid seeds.

In subsequent visits and in meetings with Chinese visitors, Branstad has continued to work to promote Chinese imports of Iowan products. According to the U.S. government, China bought about $2.5 billion in goods and services from Iowa in 2015, ranking as the state’s third largest export market. China accounted for about 9% of Iowa’s total exports. Corn, tractors, and brewing waste were the top exports. (By comparison, California exported over $20 billion and Washington exported over $16 billion in goods and services to China in 2015.)

Branstad’s most recent trip was a week after this year’s election. This time he was pushing Chinese and Japanese to buy Iowa’s pork and beef. Japan is Iowa’s most important market for meat products, but in September China reopened its beef market to American exports. For thirteen years, U.S. beef was kept out owing to fears over mad cow disease. Officials and exporters hope that American beef can win Chinese market share away from Australia and Brazil. Beef consumption in China has risen quickly and imports have doubled since 2013.

But it isn’t just that Branstad has worked to promote his state in China that caught the president-elect’s eye. The governor criticized Trump’s December statement that the U.S. should temporarily ban Muslims from entering the country. He said America needed someone with experience and a bit of nuance as president. By January, though, Branstad was impressed by the crowds Trump was getting in the state, noting that Trump was giving voice to the dissatisfaction many felt. Branstad formally endorsed Trump in May. On November 6, just before the election, six-time governor Branstad joined Trump at a Sioux City rally and Trump said, “you would be our prime candidate to take care of China.”

It was during his “thank you” rally in Des Moines on Dec. 8 that Trump formally announced Branstad as his choice.

One of the China-Iowa stories that wasn’t highlighted in discussions of Branstad’s nomination was the conviction this year of Mo Hailong, a Chinese citizen, of trying to steal high-yield, pest resistant bio-engineered cord seeds. Mo worked for Dabeinong Technology Group. His sister is married to the billionaire head of the firm. Mo was convicted of sending hundreds of kilograms of seed to China where they were counterfeited. Mo was confronted in a DuPont Pioneer research field near Tama, Iowa in May 2011. He fled, but was soon under a FBI microscope. He was subsequently monitored acquiring seeds by pretending to be a grower, visiting other research facilities, trying to ship seeds to Hong Kong, and stealing corn from research fields. He was arrested and charged with theft of $30-40 million worth of bioengineering secrets. Charges against Mo’s sister were dismissed and his other alleged co-conspirators had already left the U.S. Mo pled guilty in January and in October was sentenced to three years in prison. He is also supposed to pay restitution.

Weak Chinese enforcement of intellectual property rights will be among the issues that Branstad must deal with, assuming he’s confirmed by the Senate to replace Max Baucus as America’s chief representative to China.

*****

Baucus and now Branstad join other political veterans sent to Beijing. The first head of the U.S. liaison office was George H.W. Bush. He had served Richard Nixon as ambassador to the United Nations during the time that the People’s Republic replaced the Republic of China (Taiwan) in the UN and on the Security Council and he had chaired the Republican National Committee before President Gerald Ford sent him to Beijing. Thomas Gates, Jr. (a former Secretary of Defense) and Leonard Woodcock (a former head of the United Auto Workers) succeeded Bush at the liaison office. Midway through Woodcock’s four years in Beijing, President Jimmy Carter and Deng Xiaoping agreed on formal diplomatic recognition, a process that included severing official ties with Taipei, a process that Donald Trump’s phone conversation with Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen last week brought back into the news.

For the next fifteen years in the 1980s and 1990s, veteran diplomats with a China focus served as the American ambassador to China. This included Arthur Hummel Jr. (1981-85) who was born in China to missionary educators (and whose uncle William taught at the University of Nanjing and USC). Winston Lord (1985-89) was an assistant of Henry Kissinger’s and had been part of the 1971-72 rapprochement with Beijing. Jim Lilley (1989-91) was born in China and spent the first dozen years of his life there. He joined the army and then the CIA, becoming the top China specialist there by 1975. Before serving as ambassador in Beijing, he had served in the liaison office there, had headed America’s unofficial office in Taiwan and was ambassador to South Korea. He had close ties to the man who appointed him, George H.W. Bush, who had headed the liaison office while he was there and was also a former director of the CIA. Like Hummel and Lilley, J. Stapleton Roy (1991-96) (2007, 2014 talks) was born in China. He had served at the liaison office and embassy for three years before serving as ambassador to Singapore and Deputy Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs.

Since Roy, America’s chief representatives have included political veterans such as Jim Sasser (1996-99), a three-term senator and friend of Vice President Al Gore, and the former head of the U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Joseph Prueher (1999-2001). Prueher was in Beijing when one of the first U.S.-China dust-ups in the South China Sea took place. On April 1, 2001, a U.S. Navy reconnaissance plane was intercepted by Chinese fighter jets in international air space off China’s southern coast. The resulting collision killed the Chinese pilot and forced the U.S. crew to make an emergency landing in China. The stand-off was eventually diffused, though disagreements persist between the U.S. and China over what activities are permitted outside a nation’s territorial waters and air space. The latest incident took place Thursday when the Chinese navy seized a U.S. naval underwater drone as it was being collected off the coast of the Philippines.

Prueher was replaced by Clark “Sandy” Randt. Randt was a college buddy of President George W. Bush and was a veteran China-focused attorney. He wound up becoming America’s longest serving ambassador to China (2001-2009). He was succeeded by Jon Huntsman, Jr. (2009-11), Utah’s governor and a former diplomat and trade official. The Republican had been a missionary to Taiwan and spoke Chinese. As his successor, President Barack Obama appointed Gary Locke (2011-14), the first Chinese American to serve as ambassador to China. Locke had served two terms as governor of Washington and was Obama’s first Secretary of Commerce, working to expand U.S. exports to China and elsewhere. Chinese remember him for carrying his own bag and buying his own coffee and for broadcasting the air pollution readings taken from the embassy roof. When Locke stepped down in 2014, Obama chose Max Baucus. Prior to this, Baucus had represented Montana in Washington for almost forty-years, including six terms as a senator. Baucus had long pushed for stronger trade ties with China and had supported China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, the fifteenth anniversary of which was this past week.

*****

The U.S. relationship with China is multifaceted and evolving. There are many issues that the new ambassador understand well, but others that he’ll need to study. President-elect Trump has said that he likes the idea of America being less predictable in the international arena. Many in the security, diplomatic, and business spheres fear just that.

Branstad, too, will take office in a new era where the top U.S. and Chinese leaders meet frequently as part of strategic dialogues and on the sidelines of multilateral gatherings. President Obama’s first meeting with then Chinese President Hu Jintao was at the G-20 Meeting in London in April 2009. His last meetings with President Xi were at the G-20 Meeting in Hangzhou in September and at the APEC Meeting in Peru in November.

*****

Thank you for reading Talking Points. Please share it with friends and colleagues and encourage them to subscribe. We’d love to hear from you. You can reach us via email or via Facebook or Twitter.

Please support the USC U.S.-China Institute with a tax-deductible donation. We are eager to continue our efforts to inform public discussion of the multi-threaded and always changing U.S.-China relationship. We need your help.

Best wishes,

Keep us out of your spam/promotion folder - add uschina@usc.edu to your address book.

Upcoming USCI Events

Submit Event

John Birch, China, and the Politics of Conspiracy

March 2, 2017 - 4:00pm

March 2, 2017 - 4:00pm March 9, 2017 - 4:00pm

March 9, 2017 - 4:00pm