Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

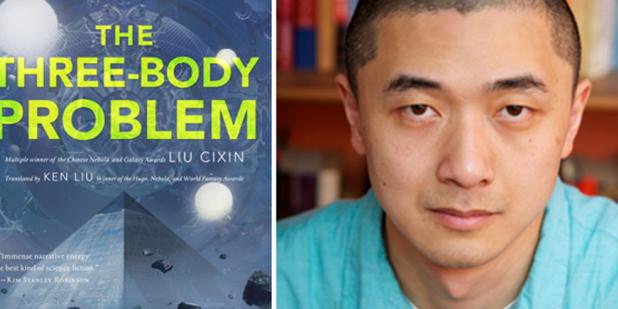

Q&A With Ken Liu, Translator of "The Three-Body Problem"

Originally published by US-China Today on 9/11/2015. Written by Catherine Wang.

Ken Liu, author of "The Grace of Kings," is a Chinese-American writer of speculative fiction. His 2011 short story "The Paper Menagerie" was the first piece to ever sweep the Hugo, Nebula, and World Fantasy awards, and his work as a translator has also brought him acclaim. Most recently, he translated into English Liu Cixin’s science fiction novel "The Three-Body Problem," which received the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel, a first for a Chinese work and for any work that originated in another language. US-China Today talked with Mr. Liu about his experiences as a writer, the influence of his Chinese heritage, and challenges he faces as a translator.

What inspires you to write speculative fiction and poetry?

I think all fiction (and perhaps all poetry) is "speculative."

The primary markers of fiction are a particular set of rhetorical modes (which are increasingly found in nonfiction as well) and a relative privileging of the logic of metaphors. Science fiction and fantasy tales, or "speculative literature," simply literalize these metaphors more often than so-called "realist" literature, and I enjoy playing with literalized metaphors.

What is your general process and approach to translating others’ work?

I view translation as a performance art -- I believe William Weaver was first responsible for this metaphor. The key, for me, is understanding the effect the original author was trying to achieve with her words, and then finding ways to re-create that effect in a new linguistic community and culture.

Because translation is a performance, there is a great deal of creativity and judgment involved, but they are different from the kind of creativity and judgment required for writing original fiction, and it's always interesting for me to contrast these differences.

When you translate works between Chinese and English, what challenges do you face? How did you translate "The Three-Body Problem" to be more accessible, culturally and linguistically, to English-speaking audiences?

When you translate works between Chinese and English, what challenges do you face? How did you translate "The Three-Body Problem" to be more accessible, culturally and linguistically, to English-speaking audiences?

I think the biggest challenges are not linguistic, but cultural. Sometimes those who are not familiar with the art of translation focus on things like "untranslatable words" or grammatical differences between languages. These, in my view, are minor issues. The differences in the cultural assumptions of readers in the original language and in the target language are far more challenging.

For instance, Chinese has developed, over time, a rich set of forms of address (including titles, honorifics, diminutives, nicknames, etc.) that expresses subtle and complicated social relationships and judgments with a single word. These forms of address have become even more complex due to China's recent history -- a semi-colonial legacy, the May-Fourth Movement, the Communist Revolution, the Cultural Revolution, the economic reforms, the influences from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and the West, the growing impact of English and online culture ... -- every social upheaval has rearranged social expectations and hierarchies. It is impossible to properly convey all the complicated layers of history and shifting meanings behind a form of address like "xiaojie," "laoshi," or "shifu" in English because our histories and cultural expectations are so different, and we lack the supporting web of background knowledge and assumptions that Chinese readers have. Footnotes and explanatory glosses help, but they only go so far.

In my translation, I generally try not to worry too much about "losses" -- some losses are inevitable when the source and target cultures are as different as contemporary China and the United States. I try to focus on gains: new readers for visionary works; some inter-cultural understanding, even if heavily filtered; making the world seem just a bit smaller and more comprehensible.

What does the success of "The Three-Body Problem" mean to you personally, and how do you think it will impact the future of Chinese science fiction?

I loved "The Three Body Problem" as a fan, and it's absolutely wonderful to be able to share it with my fellow Anglophone readers and to celebrate the global flowering of SFF [science fiction and fantasy].

Since I'm not a Chinese SFF writer, I can't really say anything intelligent about how it will impact the future of Chinese SFF in China. But from my American perspective, I hope it will increase the willingness of publishers to bring more translations here and encourage readers to buy and read them.

How does your Chinese background and knowledge of East Asian history influence your writing?

I'm lucky to inherit two quite distinct literary traditions. One of them, the Western canon, encompasses the Greek and Latin epics, Anglo-Saxon poetry, Renaissance vernacular compositions, and all the "great books" of the Anglo-American tradition, including diverse contributions from all authors in our multi-ethnic nation-state. The other one, Chinese literature, covers Warring States and Spring and Autumn lyrics, Classical poems and essays, historical romances and vernacular novels, as well as more contemporary contributions like wuxia fantasies and chuanyue web serials. The combination gives me more aesthetic vantage points and narrative tools to deploy in my own writing, and allows me to question assumptions that may be held sacrosanct if I relied exclusively on my Western literary heritage.

In an interview with Wired Magazine, you said that your debut novel The Grace of Kings explores a changing world and the “necessity of revolution.” What role do you feel literature, especially science fiction, plays in modern social revolution?

What we find persuasive in fiction -- emotional truth -- is quite different from what we find persuasive in expository writing. But emotional truth does not exist in a vacuum. It is heavily dependent on an interplay between the reader and the text and the shared assumptions in the interpretive context in which the reader is embedded.

When readers view fiction as containing a "message," I believe most of the message comes from the reader. Louis Menand wrote, when discussing Joan Didion, that "[t]exts are always packed, by the reader’s prior knowledge and expectations, before they are unpacked. The teacher has already inserted into the hat the rabbit whose production in the classroom awes the undergraduates."

I think Menand is right. As a tool of social revolution, fiction does not function like nonfiction, and cannot be analyzed in the same way.

You share on your website that you like “sentences that sound perfect in only one language.” Can you share one of those sentences?

尋尋覓覓,冷冷清清,淒悽慘慘戚戚。

That's probably the most famous line from the Song Dynasty poet Li Qingzhao. I'm not going to translate it because it wouldn't sound right.

Do you draw parallels between your work as a writer, lawyer, and programmer? If so, in what ways?

All these professions involve the creation of structures within rule-based symbol systems to achieve specific results (a program that sorts numbers; a contract that gives the investor control rights; a poem that makes the reader feel mono no aware).

I do view all of them as various manifestations of the general practice of engineering.

What are your future plans as a writer?

My debut novel, a silkpunk epic fantasy called "The Grace of Kings," is now out from Simon & Schuster's new Saga imprint. It's been called "Romance of the Three Kingdoms with battle kites, War and Peace with airships, and The Iliad with submarines.”

I'm working on the next two books in the series (I'm signed for a trilogy), and I can't wait to share them with readers.

Next year, I'll have my first collection of short fiction out, called "The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories," which will include most of my award-winning short fiction plus at least one new story. And later in the year, I look forward to the publication of "Death's End," the final volume in the "Three Body" series, which I also translated, and "Invisible Planets," a collection of contemporary short Chinese SF that I translated and edited.

Let’s say you’re a character in a science fiction novel. If you could travel back in time to give advice to your college-age self, what would you say?

All these things you're stressing out over? Very few of them will turn out to matter at all. Spend more time off campus; go on more dates and take more weekend trips; stop working on that paper for Moral Reasoning -- it's a waste of time and you'll get a C no matter what; also, buy some shares of Apple. You'll thank me later.

Featured Articles

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

Events

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?